If three, as the old saying goes, makes a trend, the museum world is past that and into institutionalizing the idea of multi-sensory exhibitions. I still would call it a “mini-trend,†though–one that I wrote about for The New York Times in its annual Museums section, published in print today.

If three, as the old saying goes, makes a trend, the museum world is past that and into institutionalizing the idea of multi-sensory exhibitions. I still would call it a “mini-trend,†though–one that I wrote about for The New York Times in its annual Museums section, published in print today.

My article, headlined Drinking In the Art: Museums Offer a Growing Banquet for the Senses, includes these summary paragraphs:

Museums usually aim to offer a feast for the eyes, but [the Detroit Institute of Art] had much more in mind for “Bitter|Sweet: Coffee, Tea & Chocolate,†which just closed at the institute. Officials, who used art objects to illustrate how the introduction of those beverages to Europe in the 16th century from Africa, Asia and the Americas changed social and consumption patterns, wanted the exhibition to be a banquet for all five senses.

After giving a few more examples, I added the rationale:

“We’re interested in multisensory exhibitions because people come to a museum not just with their eyes but with their whole bodies,†said Swarupa Anila, head of interpretation at the Detroit Institute. She labeled them an “experiment.â€

You can read the rest on the NYT site via the link above.

I could have added a few more examples: when the Musee d’Orsay exhibited Impressionism and Fashion a few years ago, I’m told it grouped all of the outdoor scenes in a large gallery at the end, with AstroTurf and chirping bird sounds. I don’t recall that when I saw it at the Metropolitan Museum. Also, I understand that the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, when presenting Luxury: Treasures of the Roman Empire last year, incorporated “a smelling station for visitors to sniff the different scents of Roman perfumes, and a digital interactive …allow[ing] visitors to virtually “try on†different hairstyles that were all the rage in ancient Rome.â€

These ideas can be hokey, and too many of them would be awful. But every now and then, when the subject demands it, I think multi-sensory exhibitions, done properly, can be interesting. I agree with what Virginia Brilliant, curator at the Ringling Museum, told me: “There’s only so much a curator can say — sometimes you just have to experience an object.†A great example, at the Ringling, during “A Feast for the Senses: Art and Experience in Medieval Europe,†visitors can view medieval manuscripts and hear the very music being played as they do.

These ideas can be hokey, and too many of them would be awful. But every now and then, when the subject demands it, I think multi-sensory exhibitions, done properly, can be interesting. I agree with what Virginia Brilliant, curator at the Ringling Museum, told me: “There’s only so much a curator can say — sometimes you just have to experience an object.†A great example, at the Ringling, during “A Feast for the Senses: Art and Experience in Medieval Europe,†visitors can view medieval manuscripts and hear the very music being played as they do.

But I also agree with what Gary Tinterow, director of the Museum of Fine Arts in Houston, told me:

“Any human being can respond to great works of art,†said Gary Tinterow, director of the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, speaking not about those specific exhibitions but the phenomenon in general. “We do not need intermediaries. We can augment the experience for children. For adults, I believe it isn’t necessary.â€

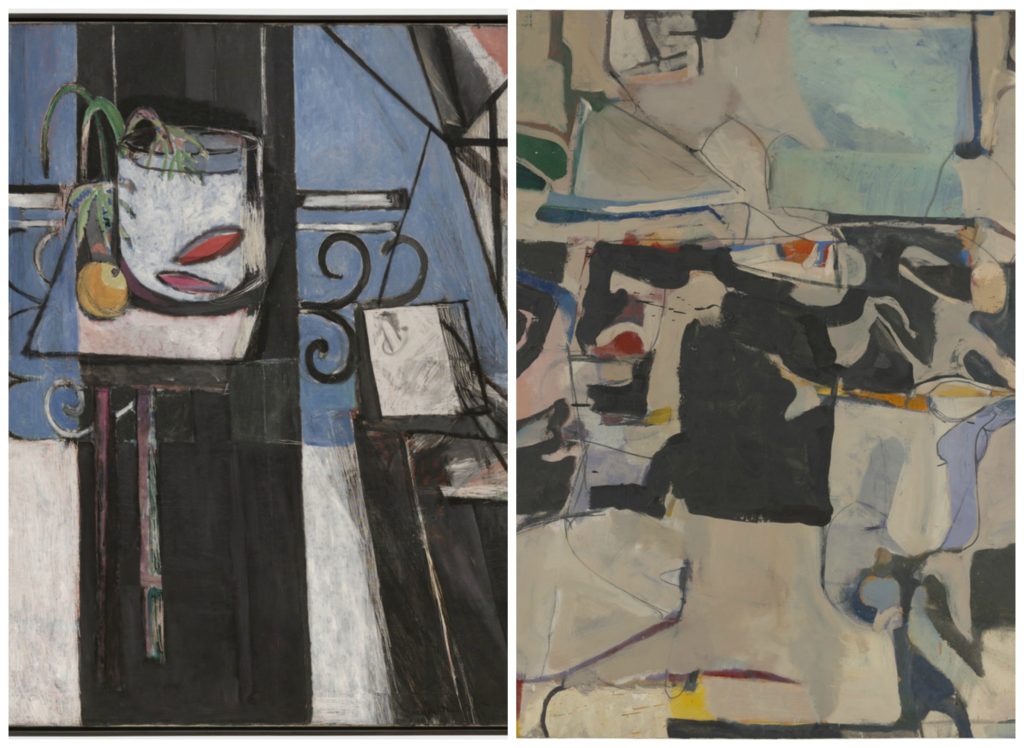

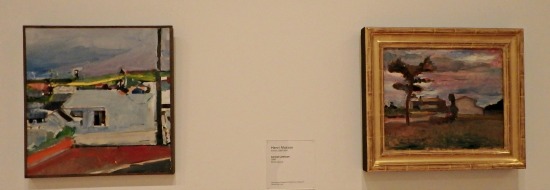

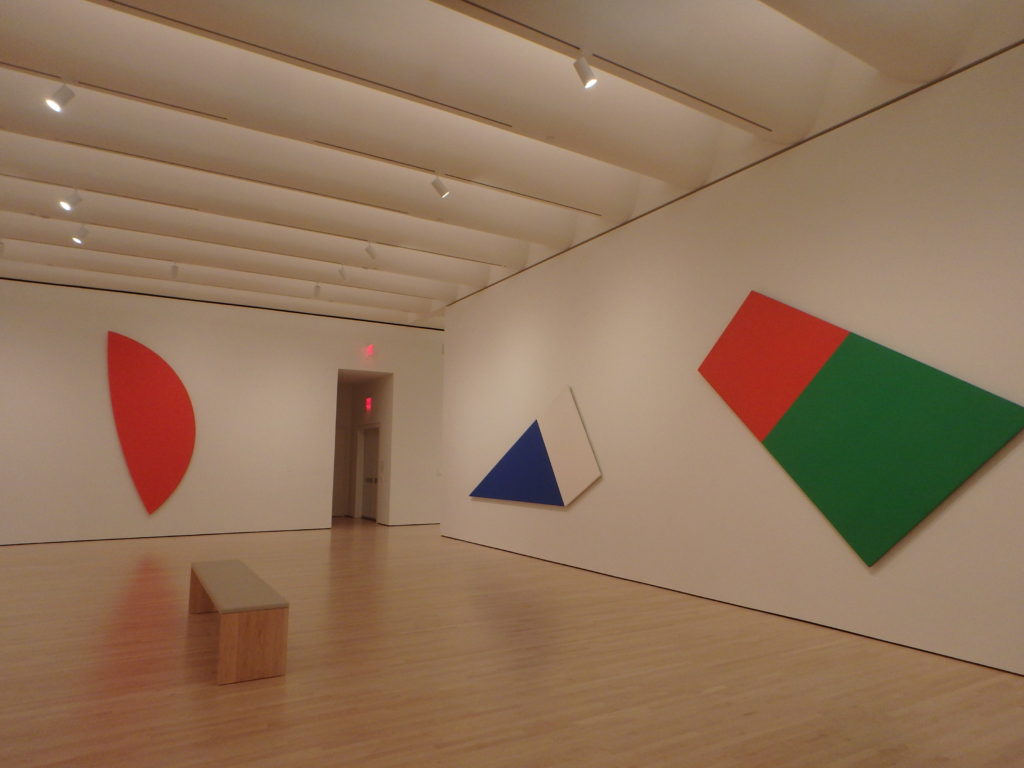

I hope museums, with this trend, act judiciously. And since I cannot post a sound, smell, touch or taste opportunity, I will simply illustrate this with a few works of art from the Medieval show, which originated at the Walters Art Museum. They illustrate touch and taste, at least.

Photo Credits: Courtesy of the Walters and the Ringling Museums