Here’s a change of pace from my last three posts, about museums.

Here’s a change of pace from my last three posts, about museums.

In the “the more things change” department: The Delaware Art Museum recently opened an exhibition that underscores the verities of the art world — maybe the whole world. Called Gertrude Käsebier’s Photographs of the Eight: Portraits for Promotion, it reveals how those artists used photopgraphic portraits and other media to promote themselves and their groundbreaking 1908 exhibition at MacBeth Gallery.

Of course, it was a different age, and they couldn’t hold a candle to artists like Jeff Koons and Damian Hirst. And they didn’t have powerful dealers like Larry Gagosian and Arne and Marc Glimcher to do it for them.

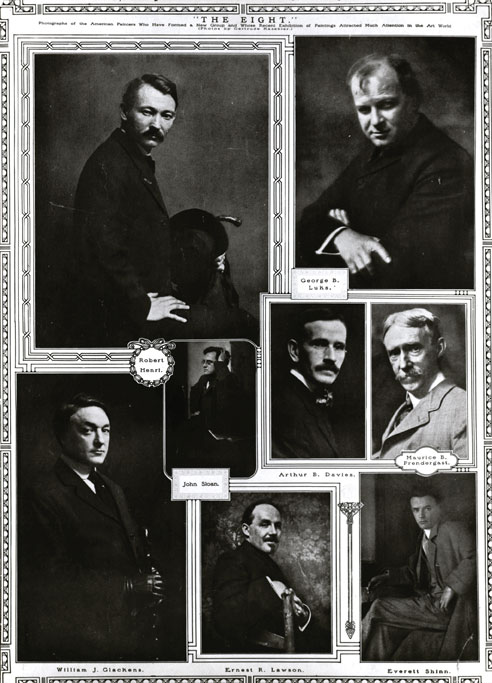

So the Eight — Robert Henri, John Sloan, William Glackens, George Luks, Arthur B. Davies, Everett Shinn, Ernest Lawson, and Maurice Prendergast — turned to Gertrude Käsebier and asked her to create “emotive and atmospheric portraits,” according to the museum’s press release. They mounted an aggressive year-long effort with the press, and the resulting articles in newspapers and magazines bore headlines like “Secession in Art,” “New York’s Art War and the Eight Rebels” and “A Rebellion in Art.” Käsebier’s portraits provided the illustrations. The articles talked about the Eight’s work and ideas about modern art. As for the show, it ran for 13 days and contained 63 pictures — but it was a watershed.

The Delaware museum is also home to a large archive whose contents include postcards between the artists, exhibition catalogs, press clippings, and a complete set of Käsebier’s portrait photographs — which are of course being used to tell the story.

The Delaware museum is also home to a large archive whose contents include postcards between the artists, exhibition catalogs, press clippings, and a complete set of Käsebier’s portrait photographs — which are of course being used to tell the story.

Käsebier (1852-1934), the museum says, “bridged the worlds of fine art photography and commercial portraiture, exhibiting her work in galleries while maintaining a portrait studio on Fifth Avenue in New York. She is considered one of the most influential American photographers of the early 20th century and is known for her powerful images of motherhood and portraits of Native Americans.”

Käsebier took up photography in her late thirties while studying portrait painting at the Pratt Institute. She worked with a chemist and a professional photographer to learn the trade and opened a New York studio in 1897. She experimented with different printing techniques and her photographs resembled works of art. Seeking to capture the individuality of each sitter, Käsebier eschewed standard studio props, relying on pose and lighting to convey character. Käsebier also participated in important photography exhibitions at a time when photographers, artists, and critics were arguing for the artistic potential of the medium.

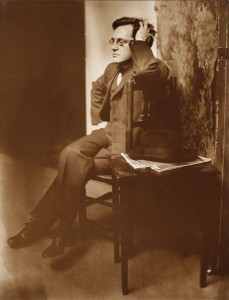

Their composite portrait is above, and at right is one of John Sloan. The Delaware museum was also kind enough to send me a wall text that tells much more of the story, which is available here.

This show, which opened on Feb. 23, runs through July 7. And the museum is presenting a talk tonight and symposium tomorrow on the show.

Photo Credits: Courtesy of the Delaware Art Museum