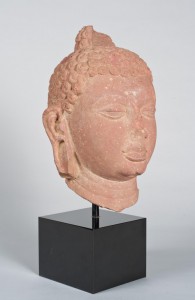

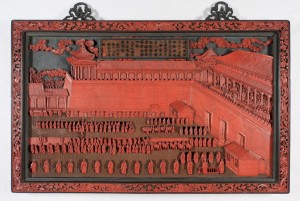

Now it’s the Carnegie Museum of Art in Pittsburgh’s turn to find fantastic art works in its storerooms, as many other museums have done. Among the newly discovered pieces: a hand-painted enamel bowl with roundels of butterflies from the Yongzheng period, a “bizarre googly-eyed dragon bowl†and cinnabar lacquer panel (below right) from the Qianlong period, a ritual bronze from the Western Zhou period, a Gupta period Buddha head (at left), a gilded bronze Thai Buddha head and a Bamana Boli figure.

Now it’s the Carnegie Museum of Art in Pittsburgh’s turn to find fantastic art works in its storerooms, as many other museums have done. Among the newly discovered pieces: a hand-painted enamel bowl with roundels of butterflies from the Yongzheng period, a “bizarre googly-eyed dragon bowl†and cinnabar lacquer panel (below right) from the Qianlong period, a ritual bronze from the Western Zhou period, a Gupta period Buddha head (at left), a gilded bronze Thai Buddha head and a Bamana Boli figure.

Many are going into a reinstallation of the Carnegie’s “Art before 1300” galleries, which will open next year. The museum says it discovered strengths, like Chinese ceramics, Buddhist and Hindu sculpture from South and Southeast Asia and African masks, that it didn’t know it had.

The Carnegie does not have a dedicated curator for either its Asian or African collections.

The Carnegie does not have a dedicated curator for either its Asian or African collections.

So, in this case, “As part of an ongoing effort to strengthen visitor engagement with the museum’s permanent collection,” it hired outside consultants to review its collections: Philip Hu for the Asian works and Jan-Lodewijk Grootaers for the African collection, which is quite small. The museum also, of course, contacted curators at other museums, who–as is practice–“generously shared information and advice,” a spokesman said. The process has been going on for four years.

From the press release issued about these discoveries, I’ve pasted a few images here.

Also, there’s this wonderful Nkisi Nkondi figure, below.

I have just a little sympathy for museums that don’t know what’s in their storeroom–but not always that much. This case is more understandable. And also credit museums for announcing discoveries like these, rather than just putting them out there, as if they knew all along. Transparency on this matter is the way to go.

Photo Credits: Courtesy of the Carnegie Museum of Art