This Sunday, the Philbrook Museum of Art in Tulsa opens what I think should be a fascinating show: IMPACT: The Philbrook Indian Annual. It’s a retrospective on the competition the Philbrook held for 33 years, from 1946 to 1979, open to Native American artists. The museum says that

This Sunday, the Philbrook Museum of Art in Tulsa opens what I think should be a fascinating show: IMPACT: The Philbrook Indian Annual. It’s a retrospective on the competition the Philbrook held for 33 years, from 1946 to 1979, open to Native American artists. The museum says that

Over the years nearly 1,000 artists from 200 Native American communities entered almost 4,000 works of art for judging, exhibition, awards, and sale. The Philbrook Indian Annual played a pivotal role in the definition of twentieth-century Native American fine art through several key aspects of the competition’s design…

It stopped before I was paying much, if any, attention to Indian art–but I can believe that the month-long Annual played an important role in the recognition of the value of Indian art. Here are some aspects of the annual that made it different, drawn from the press release:

- The Philbrook Indian Annual focused on paintings, in a variety of styles, while other juried shows of the era emphasized traditional Native art forms like pottery and basketry.

- It was a juried exhibition, not an outdoor festival.

- Jurors were mostly other Native American artists reviewing the work of their peers, rather than exclusively non-Native art critics evaluating work emerging from Native American communities.

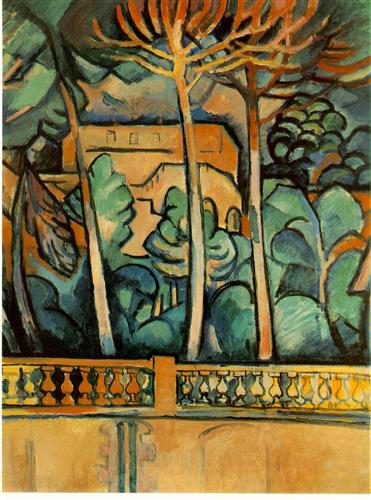

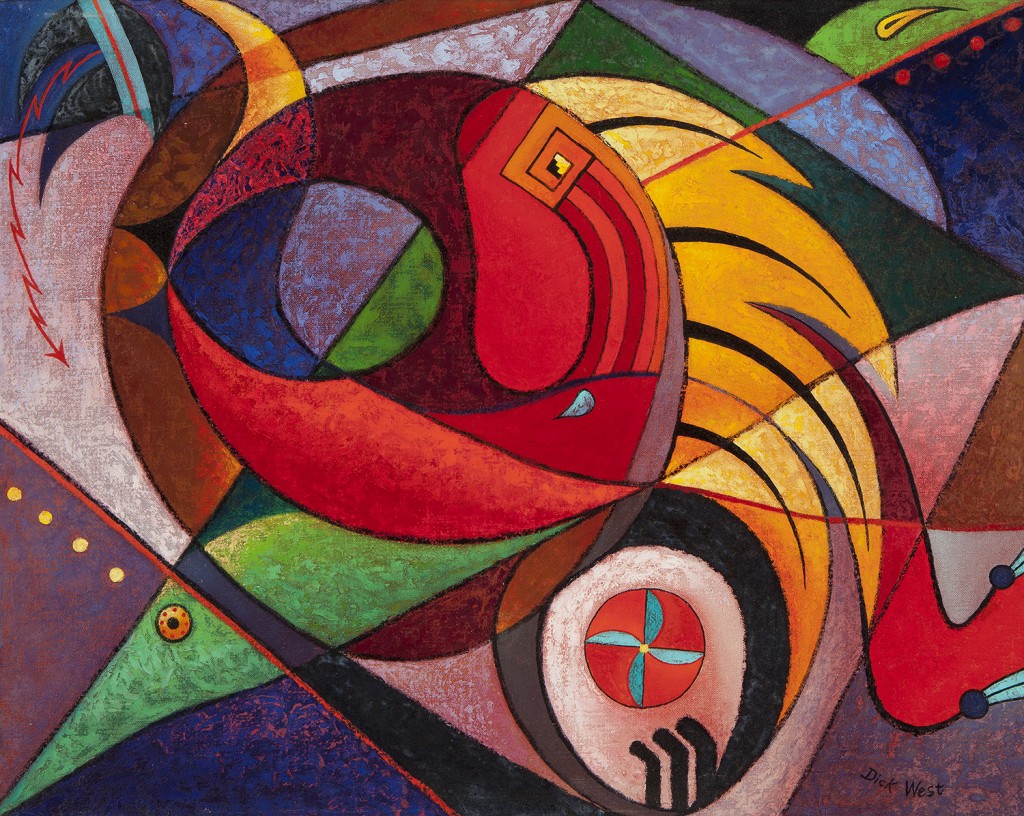

- It sparked a significant critical dialogue surrounding the definition of Native art: what it was and what it should be,  In 1958 Philbrook became the site of a national conversation about this subject when judges rejected a painting by Yanktonai Dakota artist Oscar Howe (1915–1983). They thought it was too contemporary to be Indian art. (His Dance of the Heyoka, c.1954, is above left, while  W. Richard “Dick†West, Sr.’s Water Serpent, c, 1951, is at right, below.)

Howe, who criticized the panel for its narrow view, catalyzed the Philbrook to create a new category for Non-Traditional Painting the following year, 1959.

The Philbrook’s curator Christina E. Burke organized IMPACT, drawing from the Philbrook’s permanent collection. As the release notes:

The Philbrook’s curator Christina E. Burke organized IMPACT, drawing from the Philbrook’s permanent collection. As the release notes:

The Annual helped shape the Philbrook collection into one of the finest surveys of twentieth century Native American art in the world. From the Museum’s announcement in 1938, Philbrook received important collections of such traditional Native objects as beadwork, pottery, textiles, and baskets from donors like, Roberta Campbell Lawson and Clark Field.

But I still wondered why the Philbrook discontinued the Annual. Here’s what they said:

By then [1979] the Institute of American Indian Arts in Santa Fe had opened in 1962; major museums had begun to include Native American art in their exhibitions and galleries; and media, collectors, and museum professionals began recognizing Native artists for their fine art over traditional art forms. Philbrook made its impact on Native American art through the Annual during those 33 years and encouragingly created its own obsolescence when the conversation surrounding Native American art began to evolve. We continue our emphasis on Native American fine art today through our exhibitions and extensive permanent collections at both Philbrook locations.

Clearly, what constitutes Native American art versus contemporary art continues today, at museums like the Peabody Essex and the Brooklyn Museum. The Annual may not have lost its relevance.

But there’s some good news: IMPACT may travel, the museum says.

Photo Credit: Courtesy of the Philbrook