My hat is off to Susan Leask, formerly curator of art at the Santa Cruz Museum of Art & History, and to Helen Molesworth (below), new chief curator at the Los Angeles Museum of Contemporary Art and formerly with the Institute of Contemporary Art in Boston. Both had the courage to speak publicly–in fact, in Leask’s case, to act publicly–to protest what some art museum directors are doing to undermine their jobs and, more important, their institutions.

Yes, it’s the latest discussion of the way some museums are trying to “engage” or “interact” (or choose your own verb) with the “community,” and it came in an article in Friday’s Wall Street Journal  headlined Everybody’s A Curator.

No, everyone’s not a curator.

The article this time was mainly about crowdsourcing, though that was a proxy, in some ways, for the wholesale abdication by some museums of their responsibility to be education institutions, to promote the care, understanding and appreciation of art, and to help people find meaning in art. Instead, they’d rather get big attendance numbers, no matter how they get them. The Santa Cruz museum, in this case, is exhibiting art related to the ocean “alongside works by local residents.” Notice the well-chosen word “works” not art–perhaps that’s because the “museum” encouraged people by soliciting “your two-year-old’s drawing of the beach” and “that awesome GoPro footage you took while surfing.” And so on.

The article this time was mainly about crowdsourcing, though that was a proxy, in some ways, for the wholesale abdication by some museums of their responsibility to be education institutions, to promote the care, understanding and appreciation of art, and to help people find meaning in art. Instead, they’d rather get big attendance numbers, no matter how they get them. The Santa Cruz museum, in this case, is exhibiting art related to the ocean “alongside works by local residents.” Notice the well-chosen word “works” not art–perhaps that’s because the “museum” encouraged people by soliciting “your two-year-old’s drawing of the beach” and “that awesome GoPro footage you took while surfing.” And so on.

Let me say at the outset that I am not against all crowdsourcing; occasionally it’s even thoughtful. But it often goes hand-in-hand with other measures that pander to the public, as if they could not understand great art. Leask quit the Santa Cruz institution last year because it offered a program that “invited a mix of outside professionals to live at the museum for 48 hours and build a new exhibit from the permanent collection.”

“Something about the power of art and the sanctity of the public trust had been compromised,†she told the WSJ. Later, she posted this on Facebook, as background to the comment:

I have spent my entire museum career supporting artists and their works because I believe artists are among the most important members of our society. The best of them bring insight, beauty and truth into our lives, and they all offer perspectives that may help us understand ourselves and our world better. I also support, and have included, participatory activities in exhibitions that help audiences engage with art and with each other.

As a curator, it is my responsibility to research, select and present works that have aesthetic excellence and authentic meaning, to ensure the physical integrity of those artworks, to honor the artist’s intention, and to add to scholarship that will deepen and advance the understanding of why art is crucial to all of our lives. When these responsibilities are not upheld, by the curator or by the institution, no one wins.

Amen to that.

Molesworth, meanwhile, made another point in the WSJ, in response to an exhibit at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, in which the public voted on 30 artworks, selected from 50 Impressionist paintings pre-chosen by a curator there. It was called Boston Loves Impressionism.

“You’re left with 10 paintings that may or may not make sense together, or may or may not be interesting together, or may or may not teach anything about the history of art—it’s not the stuff of knowledge or scholarship,†Ms. Molesworth said. When museum crowdsourcing is raised privately among curators, she said, the subject prompts a reaction of “silent dismay.â€

I also agree with Molesworth on the last points, which I’ve said here before: Curators have told me privately that they are distressed by these moves that disregard knowledge and scholarship, but they fear speaking up to their directors. Of course, they could be playing to my well-known feelings about these issues, but I doubt that all of them are so calculating. I have nothing to offer them, after all.

A final note: I regret to say that I will not publish comments on this post, either in agreement or disagreement.

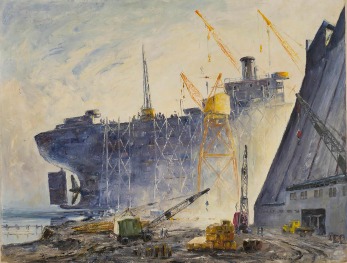

Photo Credit: Courtesy of ICA/BostonÂ