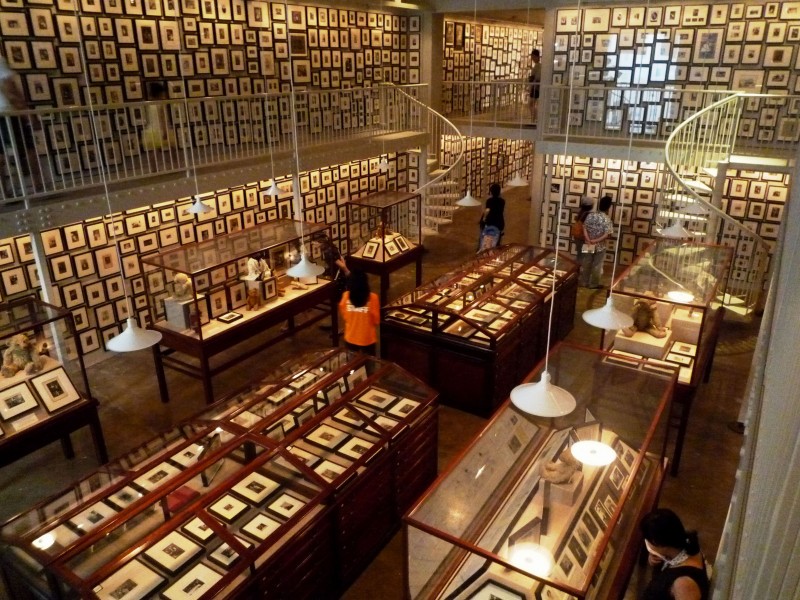

I have a high threshold for judging the merit of crowd-curated exhibits. Many, to me, just seem like pandering. But here’s one with a twist that may let it pass the test.

Over the weekend of September 8-9, between 11 a.m. and 7 p.m., people in the New York area are being invited to meet artists in Brooklyn in their studios. They can watch them work as they paint, sculpt, weave, photograph, make prints, and so on.

Over the weekend of September 8-9, between 11 a.m. and 7 p.m., people in the New York area are being invited to meet artists in Brooklyn in their studios. They can watch them work as they paint, sculpt, weave, photograph, make prints, and so on.

This open studio event, called “GO See Art IN Brooklyn,†is being sponsored by the Brooklyn Museum. Those who take advantage of the opportunity will be able to check in via text messages, something called the “GO” mobile app, or the GO mobile website.

After checking in, people will be able to to nominate three artists from their visits for inclusion in an exhibition at the Brooklyn Museum. According to a press release, “the ten artists with the most nominations will receive studio visits from Brooklyn Museum curators. Two or more nominated artists will be chosen by the curators to have their work displayed as part of a Brooklyn Museum group exhibition opening at TARGET FIRST SATURDAY on December 1, 2012.” The show continues through Feb. 24.

The artists are listed here, though you have to be patient, because they are not listed in any particular way but appear “at random.” You can, however, access them by neighborhood or see their locations on a map.

The Brooklyn Museum put out a press release with more details back in July.

Obviously, getting people into artists’ studios is good for the visual arts and for artists, which Brooklyn has a lot of. But curators have the last word. That makes all the difference, to me, in terms of validating the exercise.