Press releases often provoke more questions than they answer. That was certainly the case when one from the Los Angeles County Museum of Art issued one on Jan. 6 about its new collaboration with Saudi Aramco’s King Abdulaziz Center for World Culture. It said that LACMA and the Center:

are pleased to announce that the Center will exhibit more than 130 highlights of Islamic art from LACMA’s renowned collection on the occasion of the Center’s opening. The installation will include works of art from an area extending from southern Spain to northern India along with a never-before shown 18th-century period room from Damascus, recently acquired by LACMA.

“This is a landmark project for the museum,†said LACMA CEO…Michael Govan.

While the release mentioned “a significant partnership” with the Center “to restore and conserve the room,” details were scarce. What was the Center, which has no permanent collection at the moment–it won’t open until next year–giving in return?

I agree with LACMA’s goal to have its collection seen more broadly around the world–as long as the works of art are safe (see some listed in the press release). But was LACMA emptying its galleries of “masterpieces” and for what? Was this a “rental” deal?

A conversation with Islamic Art curator Linda Komaroff on Friday, just a day before she was head to Saudi Arabia, cleared up many questions. The answer, I think, is no.

The partnership arose after LACMA hosted a visiting curator from the Center in 2013, just when it was assessing whether to  buy a large, largely complete, lavishly decorated reception room that had been rescued from demolition (for highway construction) by Lebanese dealers in 1978. They held onto it for decades, moving it to London, and it was offered to LACMA by dealer Robert Haber.

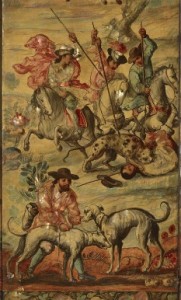

Dated 1766–67, the room measures 15 x 20 feet (“comparable in size to the one at the Met”) and was where the head of the family would have entertained honored guests. “She fell in love with the room,” Komaroff said, referring to the Saudi visitor–and the idea of a two-pronged partnership arose. The room (detail at right) was expensive and needed extensive restoration, plus the armature to hold the many pieces in place. The Center would pay for a large part of that in return for having the chance to show it and those 130 other objects from LACMA’s 1,700-item Islamic collection.

Komaroff says the room’s bright colors (the room was unvarnished) are mostly still there, though covered with dust. Here’s her description from a 2012 blog post:

As is typical, the room has colorful inlaid marble floors; painted and carved wood walls, doors and storage niches; a spectacular stone arch that serves to divide the upper and lower sections of the room, which are separated by a single high step; and an intricately inlaid stone wall fountain with a carved and painted limestone hood…

Komaroff won’t say how much it all costs, but she did say that the conservation costs were about equivalent to the purchase price, and that the whole effort was “a multi-million-dollar project.” LACMA has no acquistions fund, so she had to raise a lot of money for it, beyond what the Saudi oil company contributed.

She describes the current conservation efforts in another post, here.

The Saudis are also paying normal exhibition/loan fees for the 130-object exhibit; after the staff work, including research, required for sending the show, Komaroff says, “it’s a wash”–LACMA doesn’t make a profit on this deal. “That’s not why we’re doing it,” she added.

Lending the room next year “is okay because we don’t have a place to show it yet,” Komaroff said–it requires high ceilings; even LACMA’s Resnick pavilion, which has the highest ceiling of all its buildings, stretched only to 20 feet high. Â But the expansion Govan is contemplating should have room for it.

Komaroff compare the loan to “sending the art of the Roman empire to Rome”–a coup of sorts and something of a compliment to the collection. Saudis, she added, don’t learn visual art that goes with their history. They’ve not been exposed to much visual art.

The Center (more about which tomorrow) is also partnering with a couple of European museums.

Clearly, given the recent destruction of cultural heritage in Syria, this is a worthy effort.

Photo Credit: Courtesy of LACMA