Usually, the most noteworthy collectors–aside from those, like J. Paul Getty, with the wherewithal to buy anything they want–are the ones that go their own way, that collect a field that’s out-of-fashion but full of worthy artworks. Usually, they both self-educate and they seek expert advice.

Usually, the most noteworthy collectors–aside from those, like J. Paul Getty, with the wherewithal to buy anything they want–are the ones that go their own way, that collect a field that’s out-of-fashion but full of worthy artworks. Usually, they both self-educate and they seek expert advice.

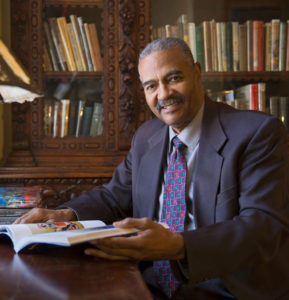

One such person is Walter O. Evans (at right), a retired surgeon who began purchasing works by African-American artists back in the late 1970s. He now owns one of the best such collections in the United States. Perhaps you have heard about him–part of his collection was on tour. The Walter O. Evans Collection of African American Art,” customized for each venue and managed by Evans’s wife, Linda, visited about 50 museums between 1991 and 2012.

Evans also donated about 60 works to the Savannah College of Art and Design in 2005, though his trove still numbers in the hundreds. As I wrote:

Evans also donated about 60 works to the Savannah College of Art and Design in 2005, though his trove still numbers in the hundreds. As I wrote:

Evans now owns works by virtually every important black artist up to and including Modernism icons Romare Bearden, Elizabeth Catlett, Archibald Motley, Robert Scott Duncanson, Mary Edmonia Lewis, Henry Tanner, Beauford Delaney, Alma Thomas, Norman Lewis, Benny Andrews, and Aaron Douglas.

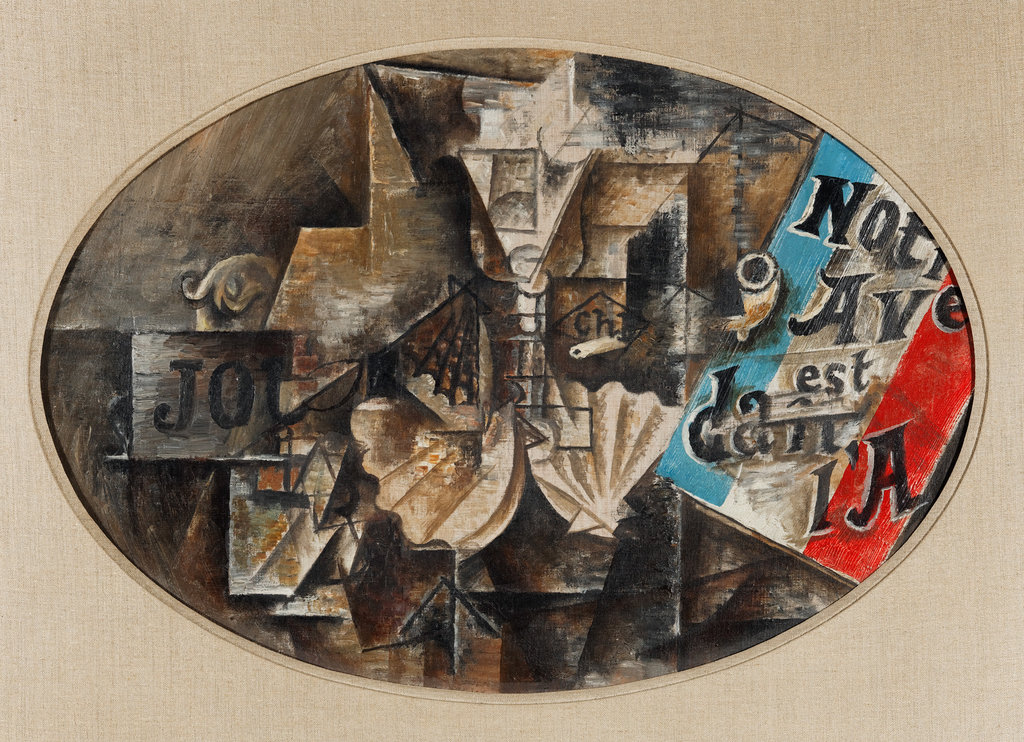

I saw a number of them myself earlier this year, when I visited his townhouse in Savannah’s historic district on assignment for Traditional Home magazine, which published my article in its October issue. More than one person I spoke with called the collection “museum-quality.” One of his works by Jacob Lawrence is at left.

Evans is an interesting guy, a pioneer in more ways than one. You can read my article about him and see more of his art collection here.

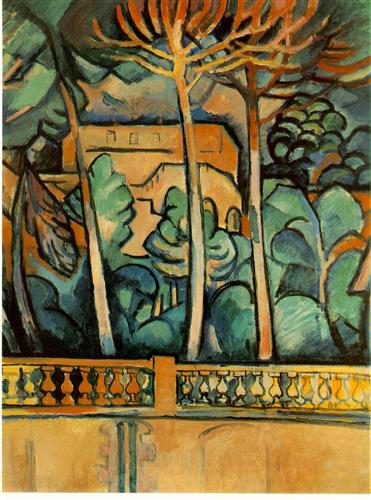

In the same issue of Traditional Home, I write about a quilt artist named Victoria Findlay Wolfe. She helped start the modern quilt movement, and is also has a very interesting story. She started as a painter and she draws inspiration from artists including Matisse.

In the same issue of Traditional Home, I write about a quilt artist named Victoria Findlay Wolfe. She helped start the modern quilt movement, and is also has a very interesting story. She started as a painter and she draws inspiration from artists including Matisse.

Furthermore, for those of you who prefer to think about quilts as craft rather than art, she has another art connection. That “Findlay” in her name refers to her husband Michael, Findlay, a director at Acquavella Galleries and author of The Value of Art.

You can read her story and see some of her quilts here.

Photo Credits: Courtesy of Traditional Home