The Toledo Museum of Art will be the place to be — ok, a place to be — next fall: it just announced a major exhibition for Manet, which it’s calling “Manet: Portraying Life.” Co-organized by Lawrence W. Nichols, senior curator for European and American painting before 1900, the exhibit will move from Toledo to the Royal Academy in London next January. It will include some 40 paintings, plus photographs, from around the world.

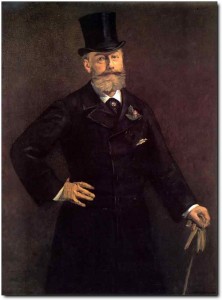

The anchor — or catalyst, if you prefer — is Toledo’s own marvelous Manet, Antonin Proust, at left, from 1880. Here’s what Nichols had to say when I asked about the show’s origins:

The anchor — or catalyst, if you prefer — is Toledo’s own marvelous Manet, Antonin Proust, at left, from 1880. Here’s what Nichols had to say when I asked about the show’s origins:

Manet as a portraitist has never been isolated as an exhibition topic, and with our collection having one of his finer examples, I determined some six years ago to make this show come to pass – here. Our partnership with the Royal Academy of Arts came about when I learned that my colleague, MaryAnne Stevens, was giving thought to preparing a Manet exhibition for London, which has never had a retrospective of the artist. I was able to direct them to this aspect of his career. Our aim: to explore the twofold character of Manet’s work in the genre of portraiture – posed portraits like our own canvas, as well as portraits of individuals engaged in the activities of everyday life.

Manet has never had a retrospective in London? How did that happen?

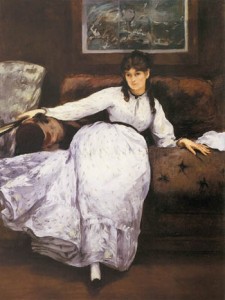

But I digress. Nichols says the show will include many of Manet’s best-known and loved works, including The Railway from the National Gallery of Art, Washington; Emile Zola from the  Orsay, Paris, and the “rarely lent gem” from RISD in Providence, Le Repos (Berthe Morisot), at right, to name a few, plus “a number of less well known works including Mme Brunet, which was just acquired by the Getty Museum, and The Bicycle (Leon Koella Leenhoff) from a private collection in Paris (which must be rarely seen, because I couldn’t find an image of it online). Here’s the press release.

I thought it was great, and possibly unusual, that Toledo is collaborating with the RA, and asked about it. “The TMA has generously lent to the RA, London, for decades, but to the best of my knowledge we have never collaborated with them on an exhibition,” wrote Nichols. My feeling is that, too often, museums collaborate with the same old partners and they need to mix it up a bit more.

I thought it was great, and possibly unusual, that Toledo is collaborating with the RA, and asked about it. “The TMA has generously lent to the RA, London, for decades, but to the best of my knowledge we have never collaborated with them on an exhibition,” wrote Nichols. My feeling is that, too often, museums collaborate with the same old partners and they need to mix it up a bit more.

This is an expensive exhibition for Toledo, but the museum has lined up sponsors and is obviously hoping for a popular success — which it should get.Â

The Museum points out that 2012 is its hundredth year in its current building, and is kind of celebrating with the Manet show and three other portrait shows — one of paintings by Toledoan Leslie Adams; another called Made in Hollywood, portraits from the studios’ glory days from the 1920s to the 1960s, and a third featuring “more than 700 [!] photographs soon to be shot of citizens of this city,” Nichols said. It’s all called “Portrait Season at the Museum,” a way of focusing on people.

The Toledo museum has an avid local fan base, and this show, which opens on Oct. 7, Â should only make them more appreciative.

Photo Credit: Courtesy Toledo Museum of Art (top)