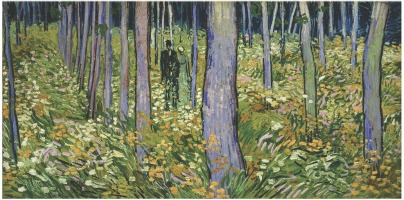

If you went to Van Gogh Up Close at the Philadelphia Museum of Art earlier this year, you saw a painting many thought was one of the stars of the show:Â Undergrowth with Two Figures from the collection of the Cincinnati Art Museum, a bequest of Mary E. Johnston accessioned in 1967.

But back in Cincinnati, Per Knutas, the former paintings conservator at the Cincinnati museum, had questions about it. When the painting (original view at left) was cleaned, he had discovered tiny traces of bright pink in the areas under the frame. On the rest of the painting, they were white. Did van Gogh use pink? For which flowers?

But back in Cincinnati, Per Knutas, the former paintings conservator at the Cincinnati museum, had questions about it. When the painting (original view at left) was cleaned, he had discovered tiny traces of bright pink in the areas under the frame. On the rest of the painting, they were white. Did van Gogh use pink? For which flowers?

Knutas called on Dr. Gregory D. Smith, the Senior Conservation Scientist at the Indianapolis Museum of Art, who agreed to examine the painting in hopes of identifying the mysterious paint colorant van Gogh used. Â Dr. Jeffrey Fieberg, a visiting researcher and Associate Professor of Chemistry at Centre College in Danville, KY, was there to help.

Now they know. The IMA Lab researchers have now determined that bright pink pigment was the original color of many of the painting’s flowers. They had “rapidly faded to white due to the properties of a dye that van Gogh often used at the end of his career,” the press release says.

Van Gogh was known to use a bright Geranium Lake organic dye, whose brilliance is short-lived when exposed to light. And the researchers knew of a letter written by van Gogh to his brother, Theo, while he was painting the work that described it this way: “. . . undergrowth, lilac trunks of poplars, and underneath them some flower-dotted grass, pink, yellow, white and various greens.â€

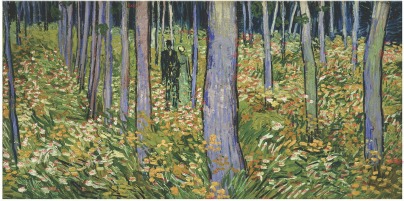

Smith utilized a small broken paint chip found lodged in the varnish to analyze the dye by Raman microspectroscopy—a process that collects a characteristic spectral fingerprint from the dye by measuring changes in laser light scattered by the molecules. Comparison of the spectrum to a digital library of thousands of materials identified the dye as eosin, which gives Geranium Lake its vibrant color. After identifying the ink, Smith and Fieberg painstakingly mapped out its location by elemental spectroscopy in the 387 dobs of white paint used by van Gogh to represent the flowers. The team used Adobe Photoshop to record all the spots in which the dyestuff was detected, creating a virtual restoration of the aged painting [bottom].

The release has more details on this painting and on one by de Chirico, and I’ve pasted the current version and the reimagined versions here — even at this size, you can see some pink in the lower one.

But here’s a possible fly in the ointment. Yesterday, the Daily Mail in London printed a story positing that van Gogh was colorblind. That’s according to a Japanese vision expert named Kazunori Asada. If you go to the article, you’ll see various pictures through normal eyes and  how they look to people who are colorblind. At the bottom are several van Gogh paintings seen the same way.

I wonder what Asada would think of the original painting.

Photo Credits: Courtesy of the Indianapolis Museum of Art and the Cincinnati Museum of Art