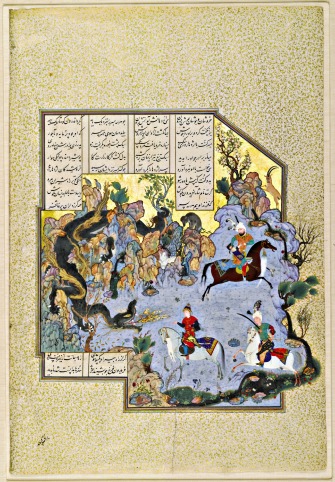

This is an example where pictures are worth a thousand words. For the past two days, the website Hyperallergic has been tracking down the storm’s impact on Chelsea art galleries and artists. Have a look at one picture below; there’s more information and pictures here and here, and Bloomberg has a short story here.

Meantime, Christie’s is offering space and computer access to dealers and artists who need that.