Poor Grant Wood. Seventy-years after his death, his work is widely known–thanks to American Gothic–but equally widely misunderstood, under-appreciated and, recalling the old insult to George W. Bush,misunderestimated. Wanda Corn tried to set the record straight in 1983, but if her excellent exhibition convinced some people–and I think it did–the effect didn’t last. That’s because, I believe, that Wood can’t shake the satirization of American Gothic.

Poor Grant Wood. Seventy-years after his death, his work is widely known–thanks to American Gothic–but equally widely misunderstood, under-appreciated and, recalling the old insult to George W. Bush,misunderestimated. Wanda Corn tried to set the record straight in 1983, but if her excellent exhibition convinced some people–and I think it did–the effect didn’t last. That’s because, I believe, that Wood can’t shake the satirization of American Gothic.

So now comes Barbara Haskell, who with Sarah Humphreville has organized an even larger exploration of Wood’s oeuvre at the Whitney Museum of American Art, an exhibition called Grant Wood: American Gothic and Other Fables. I reviewed it for The Wall Street Journal in a piece published last Thursday, and I can only hope that this time minds will be changed for the long run. He is, as I wrote, “far more complicated than his reputation as the sentimental bard of an idealized rural life and an evangelist for a pure strain of American art allows.” And:

Rather, she asserts, Wood regularly infused his meticulously planned paintings with anxiety, alienation or, at least, ambiguity. As for his call for a distinctly American art, that was more a matter of subject than style. Wood himself emulated European artists in creating his works—but they were always about American people, scenes, values and identity.

Haskell gives plenty of evidence–about 120 works, including early decorative objects, early Impressionist works, drawings, book covers and paintings that span his entire career. But she also concedes that Wood created art that can be read straightforwardly, too–his silver works, murals, those illustrations and so on. They are simply visual delights. Many portraits have only a hint of melancholy, while some other paintings are laden with significant details that can be read as signs or messages.

That’s another plus for him, btw–his work can be read on many levels.

That’s another plus for him, btw–his work can be read on many levels.

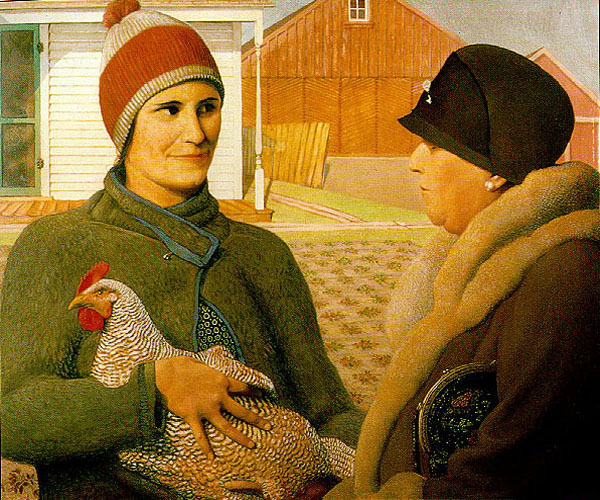

The 2010 biography of Wood by R. Tripp Evans, sees many signs of homosexuality in his works–which not something Haskell dealt much with, per se. She acknowledges that Wood’s art was influenced by his sexual repressed, closeted self, though. I don’t believe that Wood ever never acknowledged that he was gay–so her approach strikes me as reasonable. Read what you want! In Spring Turning, for example, Corn saw breasts; Haskell see buttocks, and so do I. But I do not see in the portrait of his sister, who is holding a chick and piece of fruit, a sign of anal sex, as some have.

Many things struck me as I examined this show–some I mention in the review and some only here. One thing was very, very clear, however–technically, Wood is a great painter. That’s not damning him with faint praise (read my review, please), but it is acknowledging something that has not often been mentioned about him.

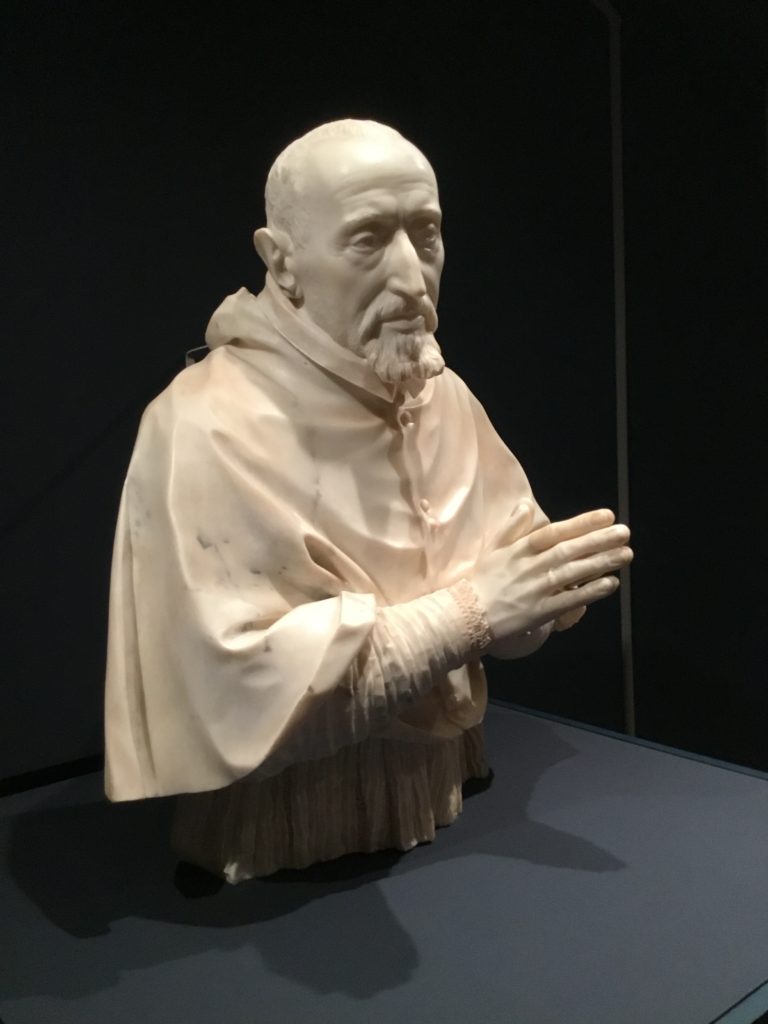

You know what American Gothic looks like, so I am posting here three other paintings that I really like. From the top: Appraisal, Plaid Sweater and Young Corn. See many more at the Whitney.