I’d wager that most people don’t think of “beauty” when they think of the art of Anselm Kiefer. So when Janne Siren, the director of the Alrbight-Knox Art Gallery, and I met last week, I was surprised by the catalogue he gave me for the Kiefer exhibition that, alas, closed there on Sunday. It was titled Beyond Landscape, and here’s part of its description:

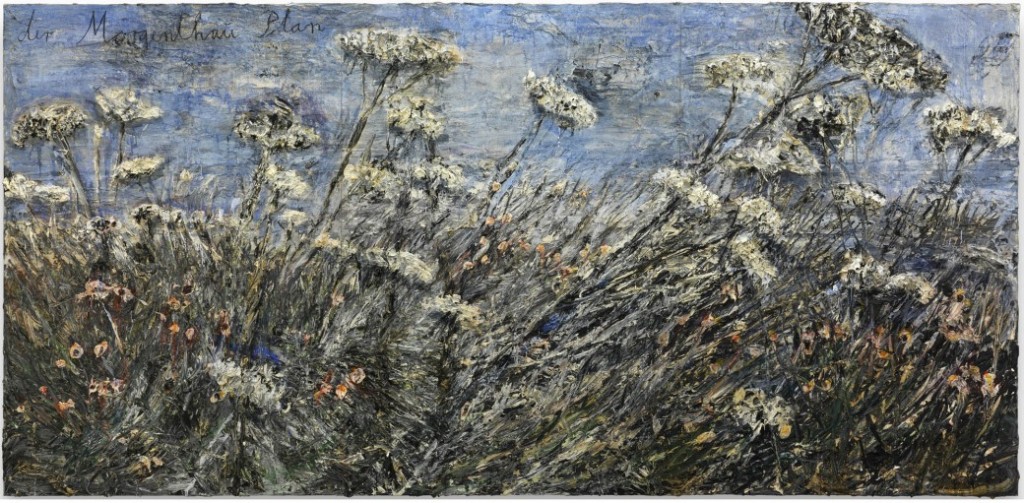

Anselm Kiefer: Beyond Landscape explores the interplay of history, identity, and landscape in the work of one of the most important artists of our time. Several major works by Kiefer (German, born 1945) form the core of the exhibition. These include the Albright-Knox’s newly acquired der Morgenthau Plan (The Morgenthau Plan), 2012, a monumental panorama inundated with wildflowers that proliferate in the landscape surrounding the artist’s studio complex in Barjac, France…

The Morgenthau Plan is indeed a beautiful piece (see below); it was on view at Gagosian in 2013. I cite it here because in the Beyond Landscape catalogue, in an interview Siren conducted with Kiefer in Croissy, France, Kiefer tells how that work came about:

I had these wonderful photographs of Barjac, of flowers, fields of poppies, all kinds of flowers, like those you find in Monet’s paintings. I liked these photographs very much.

Then here, in Croissy [near Paris, where he also has a studio], I started to paint the flowers because I wasn’t there, in Southern France, anymore. And I thought, “Ugh, flowers! What can I do with this? This is nonsense–flowers!” And I realized I needed to combine them with a negative or cynical element, and I said to myself, “Oh, I can make a Morgenthau series. And in this series Germany will be covered with beautiful flowers, will be wonderful, because as a result of the Morgenthau Plan there will be no more industry, no more highways, just flowers.” This was a cynical idea. And sometimes artists have cynical ideas–well, they feel guilty. So I felt guilty for doing these nice things, for painting pretty flowers. And then I saw how other people reacted to the paintings–they liked them so much, and I thought, “Oh!”

So Kiefer felt he could paint beauty if it were not about beauty–the Morgenthau Plan, bruited in 1944 by Henry Morgenthau, exerted revenge on Germany; it was squelched by FDR but used by Hitler as propaganda. (It’s posted online in this PDF.)

The Albright-Knox placed wall texts explaining the “cynicism” behind the work, and Siren, in the catalogue, then says “And yet I see people experiencing beauty in front of your work, and, quite frankly, I think it is okay….because for many years in Europe the art establishment regarded the very notion of beauty as something distasteful or something to be shunned….”

Not just Europe, I would add, but in the U.S. too–and it’s not over. In fact, his comments above prove that–he reacted with horror to his beautiful work because it lacked negativity.

Kiefer had a response, though:

I think beauty is first. And then comes the counterpoint. I always say that Matisse was the most desperate person. He did these wonderful paintings, just fantastic. He was not doing well at the end of his life. He was ill. He was not a pleasant man. And he was not photogenic like Picasso. But he did works that are more beautiful than those of Picasso. Beauty needs a foundation. Beauty needs a foundation.

To a certain extent, he’s right. And to a certain extent, that’s sad.

Additionally, it’s something to think about at a moment when MoMA is about to open an exhibit of Matisse cut-outs, the, yes, beautiful works he made at the end of his life.

As for Kiefer, he has a big show at White Cube in London this fall and both The Telegraph and the Financial Times have done interviews that touch further on his views of beauty.

And apropos of my recent post on the Albright-Knox’s need for expansion, the museum is buying The Morgenthau Plan (2012). Â It’s a big work–more than 9 ft by more than 18 ft. Â Where’s it going to go?

Photo Credit: Courtesy the Gagosian Gallery, photograph by Charles Duprat, via the Albright-Knox.