For those of you who questioned the decision of Alice Walton to plunk down an art museum in what to city-dwellers seemed the middle of nowhere — which I never did, being from someplace that didn’t have all that much art — it’s time to eat some crow.

Not only has Crystal Bridges exceeded attendance expectations — more than 1 million people have shown up since its opening on 11/11/11 — but also the museum has now released results of a study that is an indication of its positive impact on schoolchildren.

Not only has Crystal Bridges exceeded attendance expectations — more than 1 million people have shown up since its opening on 11/11/11 — but also the museum has now released results of a study that is an indication of its positive impact on schoolchildren.

Researchers from the University of Arkansas College of Education and Health Professions conducted the study, tracking 10,912 students and 489 teachers from 123 schools. Announcing the results, the museum said:

Each school visit includes a one-hour guided tour of the museum’s permanent collection, a discussion and activity session around a theme, and a healthy lunch prepared by Eleven, the museum’s restaurant. Teachers are able to choose from several themed tours, each designed to connect with Common Core standards at a variety of grade levels in art, history, social studies, language arts and sciences.

“Since Crystal Bridges is in an area where an art museum had not previously existed, and because the field trip is free to schools, we had high demand for the tours and decided to select participants via a random lottery,†said Anne Kraybill, Crystal Bridges’ school programs manager. “In initial meetings with the University of Arkansas, it became clear that this lottery system would provide the right conditions for conducting research.â€

Surveys of paired treatment and control groups occurred on average three weeks after the treatment group received its tour. The surveys included items assessing student knowledge about art, as well as measures of student tolerance, historical empathy, and desire to become cultural consumers….

The team also collected critical thinking measures from students by asking them to write a short essay in response to a painting that they had not previously seen. Finally, they collected a behavioral measure of cultural consumption by providing all students with a coupon good for free family admission to a special exhibition at the museum to see whether the field trip increased the likelihood of students making future visits.

And what happened? Researchers discovered that the kids remembered a lot of factual information. A few exampled:

And what happened? Researchers discovered that the kids remembered a lot of factual information. A few exampled:

- 88% of those who saw Eastman Johnson’s At the Camp—Spinning Yarns and Whittling recalled that it depicts abolitionists making maple syrup to undermine the sugar industry which relied upon slave labor.

- 82% of those who saw Norman Rockwell’s Rosie the Riveter remembered that it was about women aiding the World War II effort by entering the workforce.

- 79 % of those seeing Thomas Hart Benton’s Ploughing It Under recalled that shows a farmer destroying his crops as part of a Depression-era price support program.

- 70% who saw Romare Bearden’s Sacrifice knew it is part of the Harlem Renaissance art movement.

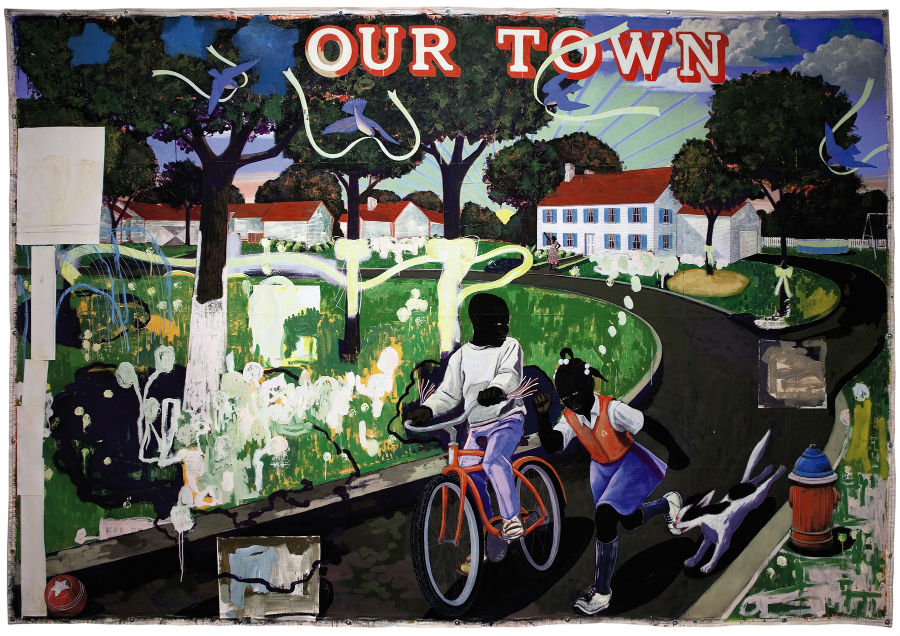

- 80% who saw Kerry James Marshall’s Our Town recognized that it offers an African American perspective of real and idealized visions of the American dream.

What about critical thinking?

All students from the 3rd through 12th grade were shown a painting they had not previously seen and asked to write short essays in response to two questions: “What do you think is going on in this painting?†and “What do you see that makes you think that?â€

“We then stripped the essays of all identifying information and had two coders rate the essays using a seven-item rubric for measuring critical thinking,†said [Jay P.] Greene, [Century Chair in Education Reform and head of the Department of Education Reform]. “We express the impact of a school tour of Crystal Bridges on critical thinking skills in terms of standard deviation effect sizes. Overall, we found that students assigned by lottery to a tour of the museum improved their critical thinking skills about art by 9.1 percent of a standard deviation relative to the control group. Rural students, who live in towns with fewer than 10,000 people, experienced an increase in critical thinking skills of nearly a third of a standard deviation. Students from high poverty schools (those with more than 50 percent receiving free or reduced-price lunches) experienced a 17.9 percent effect size improvement in critical thinking about art, and minority students benefit by 18.3 percent of a standard deviation.â€

Researchers found similar results when assessing tolerance and historical empathy, and — here’s a good ticket — students who received a tour went back to Crystal Bridges at a higher rate than those who did not.

Now, there are few questions about this — are the measures used perfect? I am no expert, but probably not. What about this incentive — “each control group was guaranteed a tour during the following semester as a reward for its cooperation.” Did that have an inevitable impact on the results? Is three weeks long enough after a visit to make the results worthwhile?

On the other hand, the researchers say that “the first large-scale, randomized controlled trial measuring what students learn from school tours of an art museum.”

Whatever you may think, it’s a good start at answering these critical questions.

For more information, you can read the report in Education Next, review a supplemental study here, see the methodology here, and view the press release here.