Max Gordon: does the name ring a bell? How about David Gordon?

A new book called Architect for Art: Max Gordon is one link between the two, but by no means the strongest: David Gordon, former director of the Milwaukee Art Museum, among other things, has written the Preface and an essay for the book about his brother Max, who died in 1990 of AIDs-related illness. I’m happy to highlight it not least because Max’s philosophy about architecture for contemporary art matches mine — or, I should say, mine parrots his: highlight the art, not the achitecture; use light to create space; make everything as simple as possible.

Max Gordon designed the Saatchi Gallery on Boundary Road in London, which opened in 1985. Among his other projects: the Fisher Landau Center for Art in Long Island City; the homes of collectors Lewis and Susan Manilow, Keith and Kathy Sachs, Jackie Brody, and his own flat in London, plus David Juda’s gallery, Annely Juda Fine Art in London. The book is illustrated with pictures of all seven. Though not in the book, Gordon’s designs for galleries in Soho (Brooke Alexander’s, to name one) later influenced those in Chelsea.

Max Gordon designed the Saatchi Gallery on Boundary Road in London, which opened in 1985. Among his other projects: the Fisher Landau Center for Art in Long Island City; the homes of collectors Lewis and Susan Manilow, Keith and Kathy Sachs, Jackie Brody, and his own flat in London, plus David Juda’s gallery, Annely Juda Fine Art in London. The book is illustrated with pictures of all seven. Though not in the book, Gordon’s designs for galleries in Soho (Brooke Alexander’s, to name one) later influenced those in Chelsea.

Nicholas Serota, director of the Tate, links Gordon’s Saatchi Gallery design directly to the hugely successful Tate Modern and credits Gordon in his essay for suggesting what became the Turner Prize. He writes:

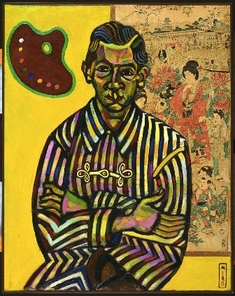

Gordon was something of a rarity, an architect…who was…loved and admired by artists. Many architects associated with artists…However, very few architects are regarded as friends and equals by artists, let alone accomplish this feat on both sides of the Atlantic. Garrulous but shy, given to one-liners but never glib, Max Gordon was a central figure in the London and New York art worlds for more than twenty years…

But why this book now? As David Gordon writes in the preface, “after excesses of all kinds, including in architecture, of the recent past, it is time for a return to an architecture infused with the spirit of minimalism, simplicity and economy.” (Another view of this is here.)

And, two, David Gordon was too busy running MAM until 2008 to get to this task.

This book has more going for it than marvelous pictures: it’s full of cocktail-party tidbits (which artists told the Sachses they must use Gordon, whose gallery he designed on the inside of a cigarette pack and whose on a napkin over lunch, etc.), as well as comments and remininscenses by Alanna Heiss, Richard Serra, Jennifer Bartlett, Lawrence Luhring, Jasper Johns, and others.

And, of course, there’s serious stuff, too — including essays by Kenneth Frampton and Jonathan Marvel.

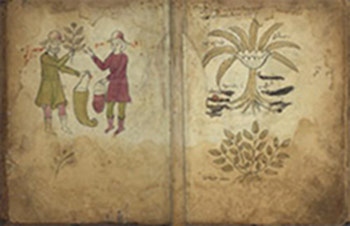

Penn recently announced that it has received a major collection of 280 Medieval and Renaissance Manuscripts, valued at over $20 million, from a Penn alum, and long-time benefactor and Library Board member Lawrence J. Schoenberg, and his wife Barbara Brizdle Schoenberg.

Penn recently announced that it has received a major collection of 280 Medieval and Renaissance Manuscripts, valued at over $20 million, from a Penn alum, and long-time benefactor and Library Board member Lawrence J. Schoenberg, and his wife Barbara Brizdle Schoenberg.