Yesterday, by chance, I was with someone who works at one of the Google 17 — the museums in the Google Art Project. She said visits to the museum’s website had skyrocketed since the announcement.

Not surprisingly, I’ve also heard that other museums are clamoring to be invited in by Google. People really think GAP is a gamechanger.

Not surprisingly, I’ve also heard that other museums are clamoring to be invited in by Google. People really think GAP is a gamechanger.

Though I am not so sure, long-term, that it will be, I decided that it makes sense to share a Q and A I read the other day with Jason Brush, executive vice president for user experience at Schematic, which was Google’s partner on GAP. Schematic, according to C-Net News, “helped integrate many of the technologies that together form Google Art Project” and “took on a lot of the heavy lifting in dealing with the various museums.”

Much of C-Net reporter Daniel Terdiman’s interview, posted here, is technical, but here are a few excerpts that reveal Brush’s sensitivity about dealing with art, about what the site is not, and :

Much of C-Net reporter Daniel Terdiman’s interview, posted here, is technical, but here are a few excerpts that reveal Brush’s sensitivity about dealing with art, about what the site is not, and :

I was awestruck by the idea itself…I could just imagine a child at a public library, somewhere in the world, who might never be able to afford airfare to travel to these museums, and who might not even have access to high-quality reproductions in books, being able to wander the halls of the great museums that the site brings together.

…I’ve worked on projects before that were groundbreaking, for which there was a great deal of pressure to get the experience right–the site we built to broadcast the Beijing Olympics online, for example–but this was different…Partially, it was because of the restraints. It wasn’t just a matter of putting up the artwork and making it accessible. There was also a lot of pressure to make sure that we weren’t making any explicit curatorial decisions. An interface can of course say something specific in and of itself, and we worked very hard to make sure that we weren’t imposing a point of view on the display of artwork.

…one of the first issues we had to face was making sure that the site wasn’t itself a meta-museum. The museums themselves have the cultural and civic onus to present the artworks in their collections in whatever way that’s appropriate to their mission….So, the pressure stemmed from not just making sure that the site was enjoyable and easy-to-use because of it’s [sic] cultural value, but also because we needed to create a model that drew a clear distinction between the live, in-person museum-going experience–which we hope the site will encourage people to have–and the experience you get online. We were in essence creating a whole new model for viewing art, which was a great responsibility.

I couldn’t agree more.

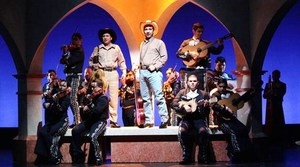

Opera companies are in the same position, only worse — they do charge upwards of $100 a ticket, sometimes way upwards of $100 a ticket. Yes, I know about subsidized tickets, but only so many people can get them, and the way they are sometimes distributed leaves out people who work and can’t stand in line.

Opera companies are in the same position, only worse — they do charge upwards of $100 a ticket, sometimes way upwards of $100 a ticket. Yes, I know about subsidized tickets, but only so many people can get them, and the way they are sometimes distributed leaves out people who work and can’t stand in line.

What makes the collection all the more interesting, according to the British press, is that many of the pictures, cleaned and restored in preparation for the show and a catalogue, tell new art-historical tales.

What makes the collection all the more interesting, according to the British press, is that many of the pictures, cleaned and restored in preparation for the show and a catalogue, tell new art-historical tales. Hence this post. The attribution research movement, if I may call it that, fascinates me. It began decades ago, and by now should have had a far bigger impact on museums.Â

Hence this post. The attribution research movement, if I may call it that, fascinates me. It began decades ago, and by now should have had a far bigger impact on museums.