If art (frequently) explores social issues, and the economy is an issue on so many people’s minds lately, is it a wonder that there haven’t been more art exhibitions about money in the last few years?

I suppose that is what drew me to the idea behind Taxing Visions: Financial Episodes in Late Nineteenth-Century American Art, which is on view at the Palmer Museum of Art at Penn State University (and will later travel to the Huntington Library near Pasadena, Calif.).

I suppose that is what drew me to the idea behind Taxing Visions: Financial Episodes in Late Nineteenth-Century American Art, which is on view at the Palmer Museum of Art at Penn State University (and will later travel to the Huntington Library near Pasadena, Calif.).

It’s a small show that showcases the responses American artists had to financial panics in 1857, 1869, 1873 and 1893. A few weeks ago, I drove down to State College, Pa., to have a look. My review of the exhibition appeared in Friday’s Wall Street Journal.

I expected a narrower version of American Stories, which ran at the Metropolitan Museum late last year and through January. But the Palmer show turned out to be a bit of a disappointment, partly because the quality of works on view was very uneven and partly because it covered a dizzying array of topics in a small number of works. The exhibit suffered, I think, because plans for a more encompassing exhibition collapsed under current financial pressures. It’s less than half its intended size, yet the catalogue shows some excellent works that could not be borrowed.

Still, this strain in American art deserves exposition and examination. Though the show includes works by Whistler, Harnett and Inness, it also shows many artists you’re unlikely to know — mostly minor ones, to be sure.

And maybe it will prompt more contemporary artists to respond to the Great Recession of today.

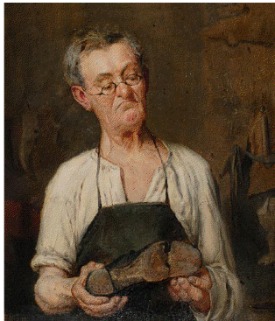

That’s Frank Moss’s Rockwellian A Difficult Job above. I like what co-curator Kevin M. Murphy wrote about it: “Perhaps tellingly, his frown repeats the arc of the shoe, as if the former is a result of his unrelenting labor on the latter.”

My visit to the Palmer a few weeks ago was my first, and since then the museum has opened another unfashionable show — At the Heart of Progress displays seventy-five prints and posters about coal production and its use in by the iron, steel, and transportation industries from the mid-eighteenth century to the present. Though it was organized by the Ackland Art Museum, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, it’s an interesting choice and, as the museum says, a show that “perfectly harmonizes with Penn State’s academic and cultural legacy.” Rather brave in this day in age, isn’t it?