Here’s another list of important cultural heritage sites to worry about: 20 “on the verge” of experiencing irreversible, irreparable loss and destruction, according to the Global Heritage Fund.

Here’s another list of important cultural heritage sites to worry about: 20 “on the verge” of experiencing irreversible, irreparable loss and destruction, according to the Global Heritage Fund.

Like UNESCO and the World Monuments Fund, GHF aims to shine a light on endangered sites; the main difference from them, as far as I can tell, is that GHF focuses exclusively on the developing world and it adds an economic argument for preservation.

In a release about its sites list, made public this morning, the GHF “estimates that there is a potential $100 billion per year opportunity by 2025 for the developing world to help achieve their UN Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) to eradicate poverty if global heritage sites are protected and preserved.”

In a release about its sites list, made public this morning, the GHF “estimates that there is a potential $100 billion per year opportunity by 2025 for the developing world to help achieve their UN Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) to eradicate poverty if global heritage sites are protected and preserved.”

And along with the release of this report, GHF is holding a conference this Tuesday at Stanford to raise awareness of the problem, identify technologies and solutions, and raise funding to get rescues started. The agenda for that conference is here.

The 20 “on the verge” sites are:

- Bangladesh’s Mahansrhangarh, monumental site of the earliest urban architecture

- Cambodia’s Sambor Preh Kok, one of the Khmer’s masterpieces in fired-brick palace architecture

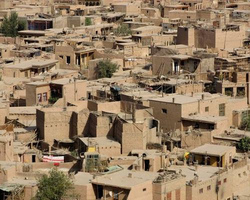

- China’s Kashgar, one of the last intact ancient cities in Asia (pictured, top left)

- China’s Jiaohe ancient city, one of the Silk Road’s greatest treasures

- Guatemala’s Mirador, the cradle of Mayan civilization

- Haiti’s Jacmel, one of the world’s last historic cities of steel and iron architecture

- India’s Maluti Temples, one of a kind edifices to the kings of the Pala dynasty

- Iraq’s Ur, where experts believe is the birthplace of Abraham (below, left)

- Iraq’s Nineveh, a major cultural center of the ancient world

- Iraq’s ancient city of Samarra

Kenya’s Lamu, East Africa’s oldest Swahili historic town

Kenya’s Lamu, East Africa’s oldest Swahili historic town- Pakistan’s Taxila, the crossroads of the ancient Indus civilization

- Palestine’s Hisham’s Palace, the sophisticated complex of the Islamic dynasty of Ummayad

- The Philippines’ historic city of Intramuros and Fort Santiago in Manila

- Syria’s Old Damascus, one of the Middle East’s last intact historic cities (top right)

- Thailand’s Ayutthaya, once one of southeast Asia’s most advanced civilizations

- Turkey and Syria’s Karkemish, one of the ancient world’s great cities

- Turkey’s Ani, the crossroads of Anatolian civilization

- Ukraine’s Chersonesos, the Black Sea’s largest classical archaeological site (bottom, right)

- Yemen’s ancient city of Zabid, once a showcase for the regions rich architectural heritage

The GHF report accompanying the list — Saving Our Vanishing Heritage: Safeguarding our Cultural Heritage Sites in the Developing World — pinned the blame for these troubled sites on five activities of man: development pressures, unsustainable tourism, insufficient management, looting, and war and conflict.

The GHF report accompanying the list — Saving Our Vanishing Heritage: Safeguarding our Cultural Heritage Sites in the Developing World — pinned the blame for these troubled sites on five activities of man: development pressures, unsustainable tourism, insufficient management, looting, and war and conflict.

It calls for “a new Global Fund for Heritage comprised of emergency funding from governments, foundations and corporations to save our remaining heritage sites – specifically focused on the poorest countries and regions of the world.”

GHF says that it’s launching a new “early warning and threats monitoring system” that uses satellite imaging technology and ground reports “to enable international experts and local conservation leaders to clearly identify and solve imminent threats within the legal core and protected areas of each global heritage site.” It calls this the Global Heritage Network.

The whole report can be accessed here and a list of the sites, with their specific threats is here. All three GHF links are work checking out, if only for the marvelous site pictures.

I suppose there’s a reason GHF started up in 2001, per GuideStar, long after the World Monuments Fund, which dates to 1965. But they share the same mission. The GHNetwork also sound much like the MEGA project recently announced by the Getty Conservation Institute, which is starting with Jordan but has the ambitions and capability of monitoring countries all over the world. I recently saw a demonstration of MEGA and it’s fantastic.

Of course, there’s plenty of work for all in global heritage — the key will be avoiding duplication and stretching dollars to their limits.