Last year the Brooklyn Museum* made good use of its collection of mummies, and now the Nelson-Atkins Museum is entering the mummy-discovery fray

Last year the Brooklyn Museum* made good use of its collection of mummies, and now the Nelson-Atkins Museum is entering the mummy-discovery fray

Brooklyn, you’ll recall, subjected four specimens to CT scans at North Shore University Hospital — and got a lot of press for it. Three doctors at the hospital analyzed the mummies, which date to as long ago as 1064 B.C. and up to 395 A.D., give or take, and discovered that one, thought to be a female, was actually a male. Among other things.

When it was all over, the mummies went back to Eastern Parkway and are now part of the museum’s Mummy Chamber semi-permanent exhibition.

The Nelson-Atkins has taken a different route, forging an unusual partnership with the federal Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives (ATF). ATF’s forensic scientists/special agents worked for more than three months on a mummy named Ka-i-nefer, who lived in Egypt 2,500 year ago but now resides in the museum’s new Egyptian galleries, which opened in May.

The Nelson-Atkins has taken a different route, forging an unusual partnership with the federal Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives (ATF). ATF’s forensic scientists/special agents worked for more than three months on a mummy named Ka-i-nefer, who lived in Egypt 2,500 year ago but now resides in the museum’s new Egyptian galleries, which opened in May.

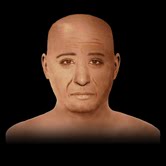

Sharon Whitaker and Robert “Randy” Strode used “a sophisticated computer program known as the Electronic Facial Identification Technique (EFIT) Program” to make a composite image of what the fellow looked like.

His composite image is above; the agents, with curators, also determined that “Ka-i-nefer was a man who lived to be about 45 to 55 years old, who stood about 5 feet 5 inches and wore size 7 shoes.”

The Nelson-Atkins is holding a presentation of these results for the public this afternoon.

Now, I am aware of the opposition to such analyses, published in a recent New Scientist article: “research on mummies is invasive and reveals intimate information such as family history and medical conditions. And, of course, the subjects cannot provide consent.”

That does give me pause. But I am rather inclined, for the moment, to agree with N-A director Julián Zugazagoitia, who said in the press release: “This sort of marriage between science and art enhances our scholarship…”

Archaeology magazine has a complete assessment of the Brooklyn adventure here, and the Brooklyn Museum has an interactive about the exercise here.

UPDATE, 9/12/10: The Kansas City Star has a nice article on the subject (here), with more detail about the process and the involvement of a local cardiologist.

Photo Credits: Courtesy of the respective museums

* I consult to a foundation that supports the Brooklyn Museum.

f that sounds a little odd, you were not a judge in the

f that sounds a little odd, you were not a judge in the  Maybe you have to see it to decide if it’s museum-worthy. But Spaid has her work cut out to persuade me.

Maybe you have to see it to decide if it’s museum-worthy. But Spaid has her work cut out to persuade me.  That caught my attention because, on the surface at least, it basically says that people don’t care enough about art to argue about it.

That caught my attention because, on the surface at least, it basically says that people don’t care enough about art to argue about it. And

And