Many museum exhibitions affect individuals; some go further, exerting influence on the collective opinion, or even beyond.

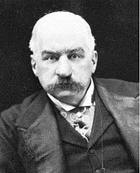

Exactly 100 years ago last night, the Metropolitan Museum of Art closed the doors on one that went further. Part of a statewide celebration, the Hudson-Fulton exhibition marked the 300th anniversary of Henry Hudson’s discovery of the river that bears his name and the centennial of Robert Fulton’s steamship. During its 10-week run, nearly 300,000 people thronged the museum’s galleries — 8,000 on opening night alone, which was presided over by J.P. Morgan, the Met’s president (left), and a 40-piece orchestra.

Exactly 100 years ago last night, the Metropolitan Museum of Art closed the doors on one that went further. Part of a statewide celebration, the Hudson-Fulton exhibition marked the 300th anniversary of Henry Hudson’s discovery of the river that bears his name and the centennial of Robert Fulton’s steamship. During its 10-week run, nearly 300,000 people thronged the museum’s galleries — 8,000 on opening night alone, which was presided over by J.P. Morgan, the Met’s president (left), and a 40-piece orchestra.

The show had two sides, and both had impact.

The “Hudson” part displayed 143 paintings by masters like Vermeer, Rembrandt, Hals and other Dutch painters from Hudson’s era, all drawn from the collections of Morgan, Benjamin Altman, Henry Clay Frick and other American business titans or their widows. These Gilded Age industrial buccaneers had spent vast sums on art-buying sprees in Europe, much to the disdain of its more-cultured citizens, who deemed them unworthy of their purchases. (Indeed, one or two turned out to be fakes.)

But after seeing the Hudson-Fulton show and visiting several private collections here, an eminent European art scholar named Ludwig Justi (right), Director of the Berlin National Gallery, was moved to dissent. Back home in Germany, Justi told a reporter from The New York Times, “I desire to be quoted in the strongest possible language as a convert from the belief that art collecting in America is the fad of millionaire ignoramuses. I must henceforth beg to disagree cordially with some of my European confreres who think that the denuding of European art collections for the benefit of America and Americans is to cast pearls before swine.”

But after seeing the Hudson-Fulton show and visiting several private collections here, an eminent European art scholar named Ludwig Justi (right), Director of the Berlin National Gallery, was moved to dissent. Back home in Germany, Justi told a reporter from The New York Times, “I desire to be quoted in the strongest possible language as a convert from the belief that art collecting in America is the fad of millionaire ignoramuses. I must henceforth beg to disagree cordially with some of my European confreres who think that the denuding of European art collections for the benefit of America and Americans is to cast pearls before swine.”

Great quote, huh? The Times printed it on Jan. 23, 1910, helping to start the passage of Americans from vacuous money-grubbers to sophisticated art collectors and appreciators in European eyes.

The Hudson-Fulton’s other side altered the course of American museums. This half displayed “industrial arts” made by colonial Americans up until Fulton’s 1815 death, plus paintings by Americans born before 1800 — including this 1806 portrait of Fulton by Benjamin West. They were also borrowed from collectors.

The Hudson-Fulton’s other side altered the course of American museums. This half displayed “industrial arts” made by colonial Americans up until Fulton’s 1815 death, plus paintings by Americans born before 1800 — including this 1806 portrait of Fulton by Benjamin West. They were also borrowed from collectors.

If the Dutch side was a shoo-in, this one was a gamble (picture of one gallery, below). American furniture, silver, ceramics and other decorative arts were then viewed as utilitarian, aesthetically inferior to European goods. The American paintings were mostly portraits, considered to be family heirlooms and not yet collected by museums.

Reviews were mixed, but the crowds appreciated what the critics didn’t. The show’s popularity reinforced the resolve of three people — Robert W. de Forest, secretary of the Met board; his wife, Emily Johnston de Forest, a daughter of the railroad baron who was the Met’s first president; and Henry W. Kent, a Massachusetts-born curator who was de Forest’s assistant — intent on rewriting that assessment of early American art.

The de Forests, aided by Kent, went on to cajole, maneuver and wait out World War I to build the Metropolitan’s American wing. They ponied up $2 million for it in 1922, hired both the architect and the contractors, and paid them directly to build a three-story building that is the core of the existing wing.

The de Forests, aided by Kent, went on to cajole, maneuver and wait out World War I to build the Metropolitan’s American wing. They ponied up $2 million for it in 1922, hired both the architect and the contractors, and paid them directly to build a three-story building that is the core of the existing wing.

The three filled the galleries, too. Mrs. de Forest purchased the first period room for the museum — a paneled wall, including the fireplace and a corner cupboard, from an 18th century home in Hewlett, Long Island. Kent scoured the Eastern states to find many more, including the assembly room in Alexandria, Va., where George Washington had once danced. It had been turned into a junk shop. They jolted many others to give to the wing and the museum trustees to buy for it.

Enthusiasm for Americana began to ripple out to the rest of the country, igniting the collecting of American antiques. Before long, Morrison H. Heckscher, chairman of the Met’s American wing, says, “it became standard practice at urban museums to have a component which included early American decorative arts, often in period rooms.”

At the Met now, I’ve seen only one reference to the Hudson-Fulton exhibit: the wall text introducing “The Milkmaid” show references a famed display of Dutch Golden Age paintings there.

But the show’s influence lives on, hopefully inspiring today’s curators as they decide the exhibits they want to organize.

Photos: Courtesy New York State Historical Association/Fenimore Art Museum (West painting), Metropolitan Museum (Hudson-Fulton gallery).