I just completed an extraordinarily smooth and successful two-day recording session with pianist Sarah Cahill for my upcoming New Albion CD. Tom Lazarus is the recording engineer, with a resumé of hundreds of great discs behind him. (One of his credits was the last recording made by Vladimir Horowitz, which made me expect he’d be a bearded patriarch; actually Tom’s my age and looks younger, and we kidded him about having worked with Horowitz at age seven.) We recorded three works: Private Dances, Time Does Not Exist, and On Reading Emerson. In a couple of weeks I’ll record two more pieces for the disc with the Da Capo ensemble and my son Bernard. I had never heard On Reading Emerson before, aside from my own halting attempts to muddle through it, and I’ve been nervous about committing to disc a piece that I haven’t heard with an audience. Listening to your music with an audience is like going over it with a microscope, and sometimes at world premieres I smack my forehead and suddenly realize what I should have done instead. But Sarah plays the piece so gorgeously that she won me over to it.

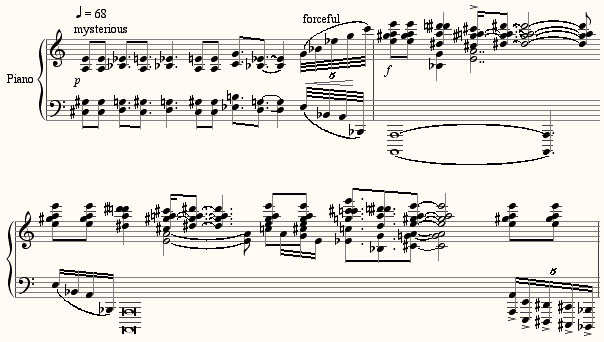

To make it scarier, On Reading Emerson, stream-of-consciousness and mercurial, is not my typical style. Sarah commissioned it for an Emerson conference she attended, and while I normally settle into a steady-state postminimalism, there was nothing postminimalist about Emerson. As Emerson so often quotes other writers, the piece wanders into motivically related quotations: from Busoni, Ives, and MacDowell, plus a phrase from an incomplete song I started in college to Emerson’s poem “Rhodora.” And since I think of each Emerson essay as driven by a single idea yet ultimately all-encompassing, I derived the whole piece from a motive that keeps reappearing at the same pitch level despite changes of key – E D# C# D# (G) – and that occasionally expands into a 12-tone row, the first one I’ve ever used. (Sort of like Strauss using a 12-tone theme in Also Sprach Zarathustra to represent “science.”) I’m so happy with it and with Sarah’s performance that I’ll treat you to a rough edit, here (eight minutes).

This is not the first time I’ve written a piece outside my usual stylistic habits and found it in certain ways more attractive than my more characteristic music. Morton Feldman used to have a standard assignment that he gave his students: “Write a piece that goes against everything you believe.” He found that his students wrote their best pieces denying all their usual reflexes. (Sort of like the Seinfeld episode in which he decides, since everything he does turns out badly, that he’ll do the opposite of his reflex habits from now on – and it works.) Feldman also had a standing offer to buy dinner for the student who could come up with the worst orchestration – and no one ever won, because the more they worked to come up with bizarre instrument combinations, the more interesting the results.

A couple of months ago, driving back from North Carolina, I chanced across a garden supply store in Virginia that advertised bird products, and, being in a mood for a break, stopped. Looking through the paraphernalia, my eye was drawn to a running video. On it spun a contraption called the “Yankee Flipper,” advertised as the world’s first squirrel-proof bird feeder: a large, clear plastic cylinder with a green metal ring at the bottom. Birds could perch on the ring and feed peacefully, but the greater weight of a squirrel, pressing the ring, set off a motor that made the ring spin around, casting the squirrel into the empyrean. I was transfixed: the sight of these squirrels being flung into the air made me laugh until tears ran down my face. You can see the video yourself

A couple of months ago, driving back from North Carolina, I chanced across a garden supply store in Virginia that advertised bird products, and, being in a mood for a break, stopped. Looking through the paraphernalia, my eye was drawn to a running video. On it spun a contraption called the “Yankee Flipper,” advertised as the world’s first squirrel-proof bird feeder: a large, clear plastic cylinder with a green metal ring at the bottom. Birds could perch on the ring and feed peacefully, but the greater weight of a squirrel, pressing the ring, set off a motor that made the ring spin around, casting the squirrel into the empyrean. I was transfixed: the sight of these squirrels being flung into the air made me laugh until tears ran down my face. You can see the video yourself