– Renske Vrolijk’s complete theater work Charlie Charlie, her well-researched and mesmerizingly beautiful postminimalist story of the wreck of the Hindenburg. That was the major Dutch premiere I flew back from London to hear last November. It’s on as I write this, and I can’t stop listening. (Note – if it sounds like the recording is playing on well-worn vinyl, it’s because Renske sampled vinyl noise and plays it in the piece’s background to evoke the milieu. Charming idea.)

– Canadian music, since I’m trying to convince even the Canadians themselves that there’s a lot of good stuff. To that end I’ve put up some pieces by Paul Dolden, whose music is parallel to M.C. Maguire’s in that it hits you with an overload of hundreds of tracks running at once. Just between the two of them, Maguire and Dolden pull the geographic center of North American hair-raising crazy-mad fanatical sonic complexity up to somewhere around Fargo. I also add some major works by that “totalist of Canada” Tim Brady, including his half-hour piece for 20 electric guitars and his Symphony No. 1, which sounds a little like Olivier Messiaen started messiaen’ around with some of Glenn Branca’s MIDI files. That’s pretty high-energy stuff too, so the station’s going through a definite uptempo phase. It must be too cold up in Canada to write the kind of slow, soft, mellow, depressing music a lot of us favor down here. You got to keep even those inner-ear follicles moving.

– Pieces by Jeff Harrington, Ben Harper, Eve Beglarian, some brand new John Luther Adams, Steve Layton, and David Borden, including several installments of his Earth Journeys for Composers (including, so far, For Alvin Curran, For Paul Chihara, and For Kyle Gann). (Hey, it’s another way to get my name on the station.) If you hear some unexpectedly conventional-sounding songs, those are Corey Dargel’s “Condoleezza Rice Songs,” so focus on the lyrics. My concept for Postclassic Radio was always as a way to get my CD collection out on the internet, and I was reluctant to use content that could already be found online, but considering so many good composers don’t have CDs out these days, I’m starting to rethink that a little.

– Some of my recent pieces that premiered lately. Since I never repeat pieces (well, almost never), my own music hadn’t had much of a presence on the station in several months.Â

More to come. Part of the hurdle is always the thought of updating the playlist, so I’ve finally decided to quit trying to make it a guide to the current station, and instead simply list all the pieces I’ve played – which I like to do as a public reminder of the incredible volume and diversity of postclassical music. I finally realized why I’ve suddenly gotten tremendously busy the last few weeks, because next month my three largest non-operatic works are being either performed or recorded. My piano concerto Sunken City needed a few minor revisions prior to its American premiere at Williams College May 9, and I’ve been making a new version of Transcendental Sonnets with a two-piano accompaniment for a May 6 performance at Bard. And I’ve been finishing The Planets, a 70-minute work I started in 1994 and which had laid dormant since 2001. The Relache ensemble is putting it on CD this summer. More of that later, soon, when everything’s finished. Meanwhile, it’ll be safe, and maybe even enlightening, to return to Postclassic Radio.

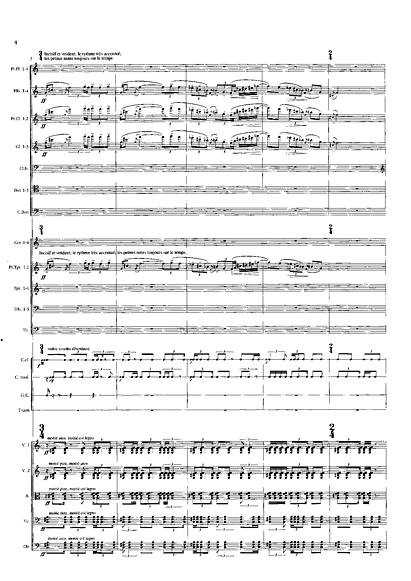

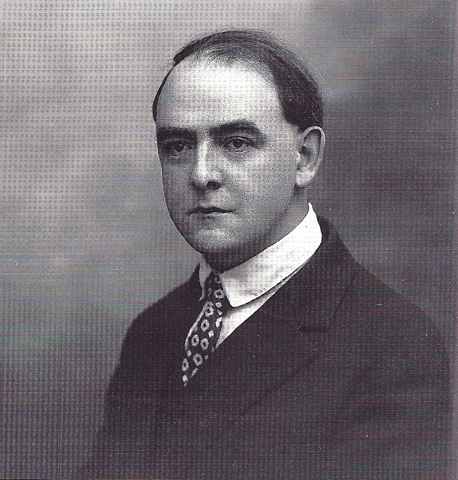

What I can do, though, is tell you about the most astonishing composer I learned about there: Matthijs Vermeulen. The Dutch call Vermeulen (1888-1967) “the Charles Ives of Holland,” and also their Varèse. He is the archetypal undiscovered composer. His Second Symphony – considered by many his most groundbreaking work (second page pictured below) – received its first performance in 1953, and Vermeulen himself first heard it in 1956. He had written it in 1920. The tone clusters, polyrhythms, percussion, and atonal counterpoint it opens with are easily as daring as anything Varèse would write in the next decade. To throw yet another comparison in, the Dutch refer to it as “the Dutch Sacre du Printemps.” Curiously modest about promoting their national composers, they won’t tell you anything about Vermeulen unless pressed, but if you mention how remarkable he was, they look proud as punch.

What I can do, though, is tell you about the most astonishing composer I learned about there: Matthijs Vermeulen. The Dutch call Vermeulen (1888-1967) “the Charles Ives of Holland,” and also their Varèse. He is the archetypal undiscovered composer. His Second Symphony – considered by many his most groundbreaking work (second page pictured below) – received its first performance in 1953, and Vermeulen himself first heard it in 1956. He had written it in 1920. The tone clusters, polyrhythms, percussion, and atonal counterpoint it opens with are easily as daring as anything Varèse would write in the next decade. To throw yet another comparison in, the Dutch refer to it as “the Dutch Sacre du Printemps.” Curiously modest about promoting their national composers, they won’t tell you anything about Vermeulen unless pressed, but if you mention how remarkable he was, they look proud as punch.