A pessimistic dinner conversation with a musicologist friend about the patent incompetence of composers with highly visible orchestral careers brings to mind David Mamet’s classic essay “Decay: Some Thoughts for Actors.†A 1986 lecture given at Harvard, it’s included in Writing in Restaurants:

We as a culture, as a civilization, are at the point where the appropriate, the life-giving, task of the organism is to decay. Nothing will stop it, nothing can stop it, for it is the force of life, and the evidence is all around us. Listen to the music in train stations and on the telephone when someone puts you on hold. The problem is not someone or some group of people unilaterally deciding to plague you with bad music; the problem is a growing universal and concerted attempt to limit the time each of us is alone with his or her thoughts; it is the collective unconscious suggesting an act of mercy….

…[T]here is a reason our civilization grew, and there is a reason it is going to die – and those reasons are as unavailable to us as the reasons we were born and are going to die….

Let’s face it and look at it: how is our parochial world decaying? The theater has few new plays and most of them are bad. The critics seem to thwart originality and the expression of love at every turn; television buys off the talented; the art of acting degenerates astoundingly each year….

…Today the job of the agent, the critic, the producer, is to hasten decay, and they are doing their job – the job the society has elected them to do is to spread terror and the eventual apathy which ensues when an individual is too afraid to look at the world around him. They are the music in the railroad station, and they represent our desire for rest.

You might say what of free will in all this, what about the will of the individual? But I don’t believe it exists, and I believe all societies function according to the rules of natural selection and that those survive who serve the society’s turn, much like people stranded when their bus has broken down. Their individual personalities are unimportant; the necessity of the moment will create the expert, the reasonable man, the brash bully, the clown, and so on.

…In this time of decay those things which society will reward with fame and recognition are bad acting, bad writing, choices which inhibit thought, reflection, and release; and these things will be called art.

Some of you are born, perhaps, to represent the opposing view – the minority opinion of someone who, for whatever reason, is not afraid to examine his state. Some of you, in spite of it all, are thrown up by destiny to attempt to bring order to the stage, to attempt to bring to the stage, as Stanislavsky put it, the life of the human soul.

Like Laocoön, you will garner quite a bit of suffering in your attempts to perform a task which you will be told does not even exist. Please try to keep in mind that the people who tell you that, who tell you that you are dull and talentless and noncommercial, are doing their job; and also bear in mind that, in your obstinacy and dedication, you are doing your job.

…[I]f you strive to teach yourself the lost art of storytelling, you are going to suffer, and, as you work and age, you may look around you and say, “Why bother?†And the answer is you must bother if you are selected to bother, and if not, then not.

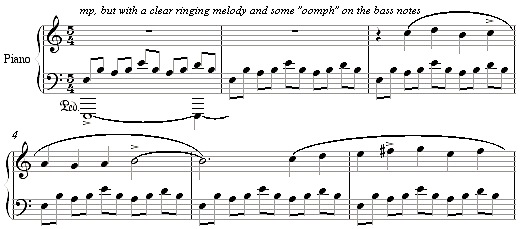

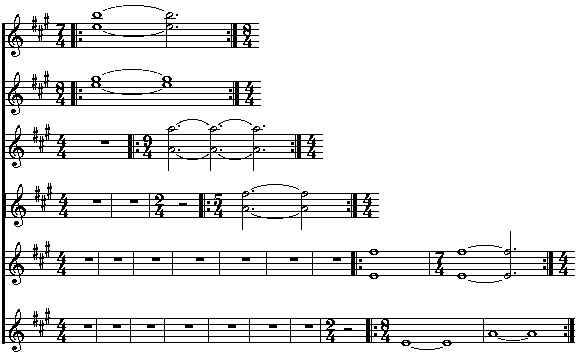

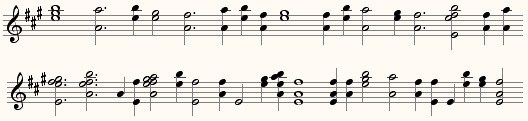

At 8:00 this Friday, March 3, at the Unitarian Universalist Church in Santa Fe, pianist Sarah Cahill will perform a concert for Santa Fe New Music that includes my own Time Does Not Exist. The devoutly American experimentalist program of mostly 21st-century music is as follows:

At 8:00 this Friday, March 3, at the Unitarian Universalist Church in Santa Fe, pianist Sarah Cahill will perform a concert for Santa Fe New Music that includes my own Time Does Not Exist. The devoutly American experimentalist program of mostly 21st-century music is as follows: