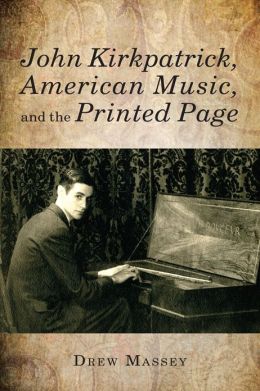

Just in time, Peter Burkholder recommended to me (announced to the entire Ives Society, actually) Drew Massey’s new book John Kirkpatrick, American Music, and the Printed Page. It’s a detailed, sometimes very technical look at Kirkpatrick’s aggressive influence as editor on the composers he adopted, including most famously Ives and Ruggles, but also Roy Harris, Ross Lee Finney, Hunter Johnson, and – ! – my old friend Robert Palmer. I can hardly say how much I admire Massey’s willingness to tackle a subject that seems to have so little profile and sex appeal on the surface, but does so much to elucidate what’s gone on behind the scenes in American music. The most telling sentence comes near the beginning: “Although many praised his commitment to American music, in the course of my research I have also heard Kirkpatrick called ‘quite a piece of work,’ a man ‘swallowed by the leviathan of [his] own conceit,’ and someone who deserved ‘a punch in the mouth.'” Most helpful for me, Massey teases out the painful process by which Kirkpatrick gradually weaseled out of helping Ives prepare a second edition of the Concord Sonata – and then spent the rest of his life making his own private editions of it with bar lines and meters and many of the sevenths and ninths “normalized” into octaves. A mesmerizing final chapter relates how the evolving editorial policies of the Charles Ives Society formed and reformed in relation and reaction to Elliott Carter’s and Maynard Solomon’s charges against Ives – and while Massey was mentored by Burkholder, who served many years as the Society’s president, and thus has an inside scoop, he does not merely act as Burkholder’s mouthpiece. One might even hope that having this historical account out in the open might cathartically bring that whole sorry issue to a close. I’ve already added a thousand words to my Concord book based on what Massey’s taught me.

Just in time, Peter Burkholder recommended to me (announced to the entire Ives Society, actually) Drew Massey’s new book John Kirkpatrick, American Music, and the Printed Page. It’s a detailed, sometimes very technical look at Kirkpatrick’s aggressive influence as editor on the composers he adopted, including most famously Ives and Ruggles, but also Roy Harris, Ross Lee Finney, Hunter Johnson, and – ! – my old friend Robert Palmer. I can hardly say how much I admire Massey’s willingness to tackle a subject that seems to have so little profile and sex appeal on the surface, but does so much to elucidate what’s gone on behind the scenes in American music. The most telling sentence comes near the beginning: “Although many praised his commitment to American music, in the course of my research I have also heard Kirkpatrick called ‘quite a piece of work,’ a man ‘swallowed by the leviathan of [his] own conceit,’ and someone who deserved ‘a punch in the mouth.'” Most helpful for me, Massey teases out the painful process by which Kirkpatrick gradually weaseled out of helping Ives prepare a second edition of the Concord Sonata – and then spent the rest of his life making his own private editions of it with bar lines and meters and many of the sevenths and ninths “normalized” into octaves. A mesmerizing final chapter relates how the evolving editorial policies of the Charles Ives Society formed and reformed in relation and reaction to Elliott Carter’s and Maynard Solomon’s charges against Ives – and while Massey was mentored by Burkholder, who served many years as the Society’s president, and thus has an inside scoop, he does not merely act as Burkholder’s mouthpiece. One might even hope that having this historical account out in the open might cathartically bring that whole sorry issue to a close. I’ve already added a thousand words to my Concord book based on what Massey’s taught me.

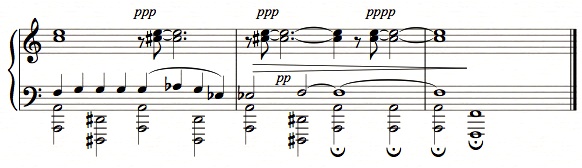

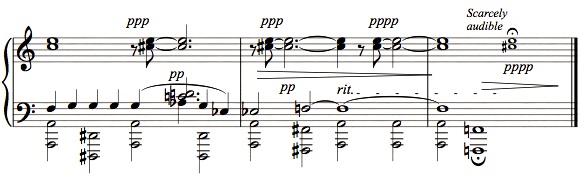

And, Americanist aficionado that I am, I gain a lot from Massey’s accounts of composers who seemed up-and-coming in the 1940s but have left little trace now. Kirkpatrick and Palmer bonded partly over their bisexuality (some of Kirkpatrick’s ideas about music were conditioned by mid-century theories linking homosexuality and immaturity), and Palmer had a rough time at Eastman because the composer-director Howard Hanson went on a crusade to cleanse the faculty there of suspected homosexuals. Well, you probably weren’t going to listen to much more of Hanson’s music anyway. And there’s enough attention paid to Palmer’s music for me to firm up my sense of why I have such a soft spot for it, like this excerpt from his Second Piano Prelude in the charming meter of 17/16:

This looks like an early piece of mine that I forgot to write. Notice the G-Ab clash in the first (actually third) measure. We need a lot more books like this, books that don’t content themselves with the public record but go backstage and unravel what ropes were being pulled by whom to make the stage machinery work. I hope Massey will expand on his research and continue shining spotlights into the dim back rooms of American music. (I shouldn’t say that, I never continue with anything. After my Cage book I was done with Cage, and after my Ives book I’ll be done with Ives. Books are how I get the music I’m wowed by out of my system.)