Bridge Records has just released a recording – the first full recording – of the Fourth Symphony, “Arcadian,” by 19th-century American composer George Bristow. This recording would never have happened without me, but you’d never know that from the CD itself.

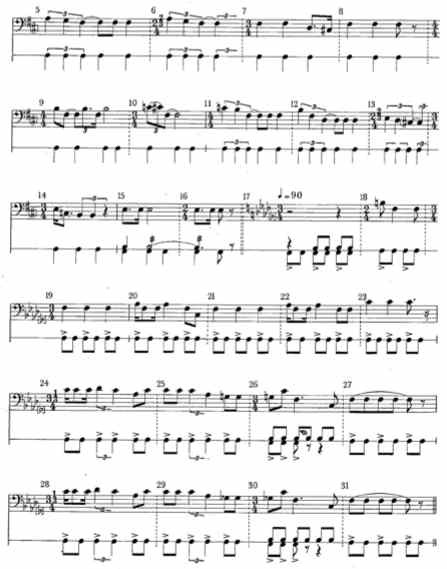

In college I studied with Delmer Rogers, who wrote the first doctoral dissertation on Bristow (1825-1898). He introduced me to the “Arcadian,” and I kept the piece in the back of my mind for decades. In 2020, in preparation for teaching a course on American symphonies, I photographed Bristow’s messy manuscript of the Arcadian at the NYPL, and began preparing a publishable edition. I mentioned it to Leon Botstein, my boss and a conductor, who took an interest in performing the piece, and subsequently recording it. I spent five or six months inputting the symphony into notation software from Bristow’s sometimes difficult-to-read manuscript, extracting the orchestra parts, double- and triple-checking everything against the original score, and then sat in on rehearsals to listen for mistakes. (Of course, I received not a cent for any of this, so Bridge is making money off my unrecompensed, now uncredited work.) Consequently, Maestro Botstein and The Orchestra Now were able to present the first performance of the piece in decades, at Bard College and at Carnegie Hall, and then record the piece for Bridge Records.

Naturally, I was asked to write the liner notes. Along with them, as usual, I submitted a brief bio, including the fact that I had prepared the edition of the symphony that made this recording possible. The Orchestra Now, in their submissions, also included a statement that this performance was based on a new performance edition by professor Kyle Gann. But for some reason the Bridge Records people didn’t want to give me credit. They nixed the paragraph from the orchestra, and, even more inexplicably, rejected the bio I had sent them and substituted another one from my web site. And so on the published compact disc I am credited only as the author of the liner notes – on a CD that wouldn’t have existed had I not devoted half a year to the mammoth job of making it possible.

Why did the people at Bridge not want me to receive credit? Old grudge? Disliked me as a critic? (In twenty-five years as a critic you make more enemies than you’re aware of.) Ungenerous and unprofessional, to say the least. The score to the Arcadian Symphony will be published soon by AR Editions, on which publication I will be listed as co-editor (with Bristow scholar Katherine Preston). So I can document that I did the work to bring this fine symphony back from the grave and into the repertoire, despite the people at Bridge not wanting you to know I did it.