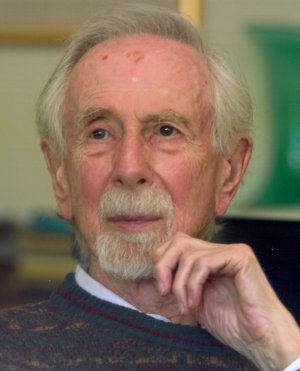

I was saddened this morning to hear from Mathew Rosenblum of the death, at age 87, of microtonal patriarch Ezra Sims. He was the pioneer of a 72edo (72 equal divisions of the octave) notation that spread among his younger colleagues in Boston and gave that city its own microtuning culture distinct from the rest of the nation. I only met him once, briefly at a Dinosaur Annex concert, but I respected his music from the first time I reviewed it in Fanfare, and we shared some jovial correspondence surrounding

I was saddened this morning to hear from Mathew Rosenblum of the death, at age 87, of microtonal patriarch Ezra Sims. He was the pioneer of a 72edo (72 equal divisions of the octave) notation that spread among his younger colleagues in Boston and gave that city its own microtuning culture distinct from the rest of the nation. I only met him once, briefly at a Dinosaur Annex concert, but I respected his music from the first time I reviewed it in Fanfare, and we shared some jovial correspondence surrounding some liner notes I once wrote for him a 2011 profile I wrote of him for Chamber Music magazine.* His music was variously capable of gnarliness, wit, and soulfulness; for the second of these, I think of his choral setting of the epigram, “There is no need / Of Andre Gide.” And of course he entered theory-class anecdotal history when Baker’s Biographical Dictionary erroneously listed him as having written a String Quartet No. 2 in 1962, and he retroactively corrected the error in 1974 by writing a quintet for winds and strings and titling it “String Quartet No. 2 (1962).” As sometimes happens, he was clearly charming beneath a curmudgeonly reputation.

I found Sims’s microtonal notation a little counterintuitive: I once inherited a composition student from him, and could never keep track of which accidentals were which. But I notice from a statement on his own web site that his interests in the harmonic series were actually pretty similar to mine:

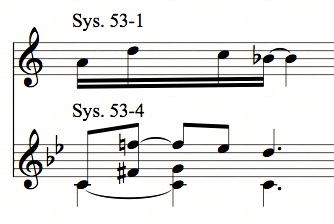

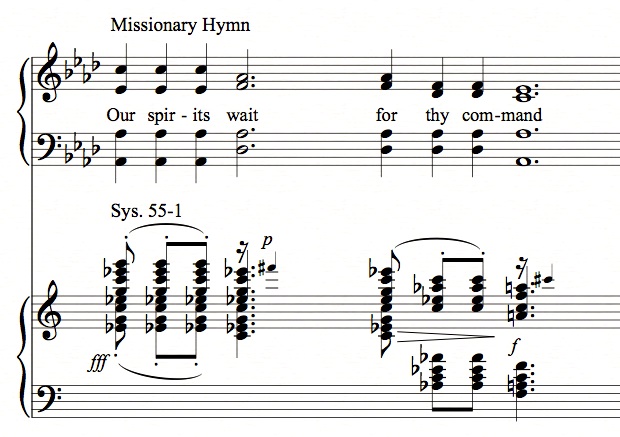

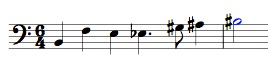

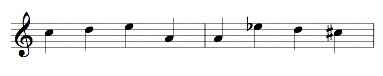

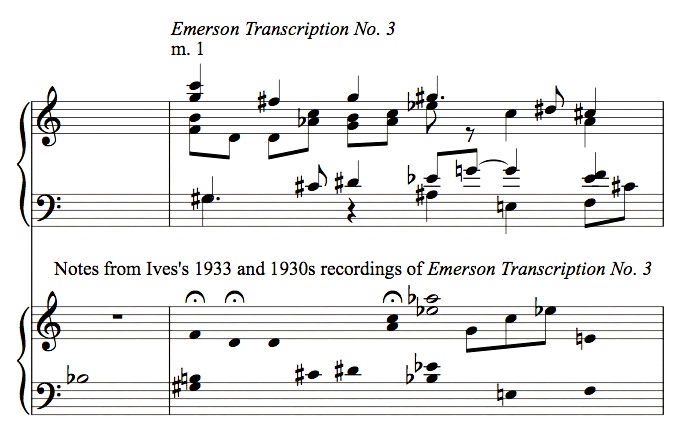

Since 1961, most of what that Ive done all my major pieces that haven’t been tape music has been microtonal. At first, it was ¼-tone, but from 1964 it has been 72-note, using at any moment one transposition or another of an asymmetrical mode of 18 or 24 pitches drawn from a 72-note division of the octave, much as Tonal music used a 7-note mode drawn from a 12-note chromatic. The mode consist of a 8 pitches of superior importance, the 8-15th harmonics of the tonic of the moment, plus 10 (or 16) chromatic pitches also drawn from its harmonic series. The 72-note division permits an all-but-exact description of the sequialteran succession of Just ratios making up the mode (25/24–30/24 [or in the alternate version: 33/32 –5/4] followed by 21/16–31/16), while retaining the conceptual and modulatory convenience of a closed cyclic notation. I trust the performers naturally to play as near Just perfection as their musicality permits, but sometimes it helps to remind them.

I suppose one could say that, aside from Harry Partch in the beginning, three seminal microtonalists seem to have determined the nature and direction of microtonal culture in the U.S.: Erv Wilson on the West Coast, Ben Johnston in the Midwest, and Ezra Sims on the East Coast.

*UPDATE: I remembered he had sent me scores of all the works on this then-most-recent CD, which is what often happens with liner notes. And since that profile isn’t online, I attach it below as a tribute:

* * * * * * * * * * *

American Composer: Ezra Sims

By Kyle Gann

Ezra Sims is probably best known, even among those who haven’t heard a note of his music, for his wry response to a musicological misprint in Baker’s Biographical Dictionary of Music and Musicians. In the ‘60s that edifying tome, then edited by Nicolas Slonimsky, attributed to Sims a work he hadn’t written, a String Quartet No. 2 dated 1962. In 1974 Sims gallantly agreed to ameliorate Slonimsky’s embarrassment to the extent that he could by writing a piece entitled String Quartet No. 2 (1962) – scored for flute, clarinet, violin, viola, and cello. As Sims notes, a title is not necessarily a description, and he cites as precedent the White Knight in Lewis Carroll’s Through the Looking Glass, whose song was called “Haddock’s Eyes†even though its title was “The Aged Aged Man,†etc. The score is dedicated to Slonimsky, “that he (or rather Baker’s) may now be less in error.â€

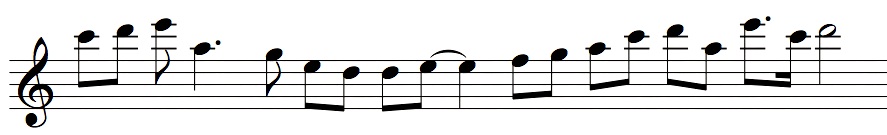

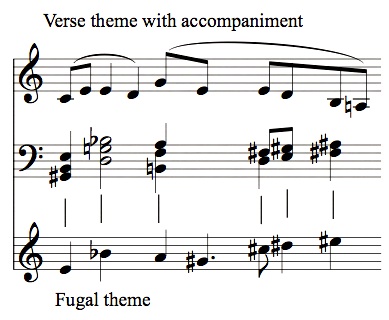

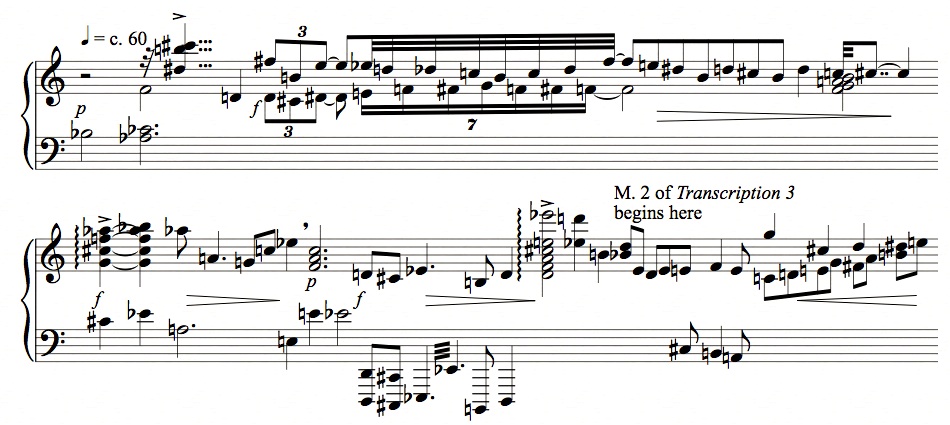

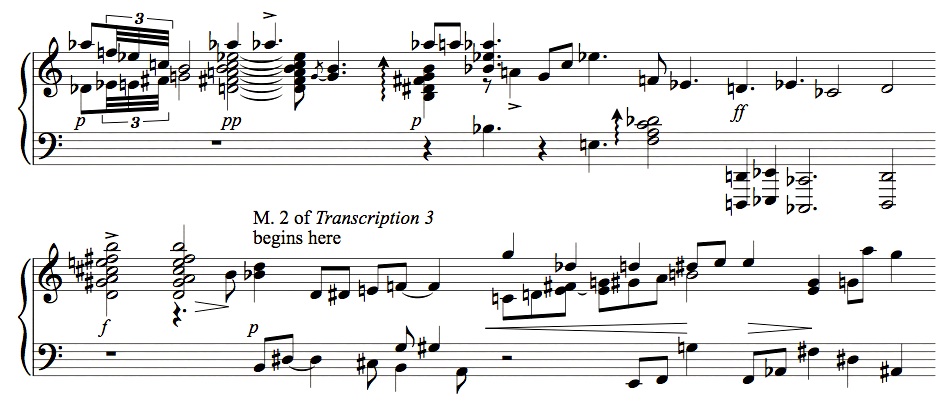

This classic and oft-noted absurdity is far from the only bit of humor in Sims’s output; he has a piano piece charmingly called Grave Dance, and a song cycle titled Brief Glimpses into Contemporary French Literature whose recurring refrain is “There is no need of Andre Gide.†But for some of us Sims (www.ezrasims.com) is less important for the dry wit threaded through his work than for his status as one of the leading composers (along with Ben Johnston) of microtonal music for traditional acoustic instruments. More specifically, Sims is the doyen of a Boston-based microtonal world in which 72 equally-spaced pitches per octave is virtually the official lingua franca. Since 1964 Sims has written in his own notation which inflects pitches upward or downward by a 12th-tone, a 6th-tone, or a quarter-tone, and the local microtonalists (James Dalton being the one exception I know of) all seem to swear by the same notation.

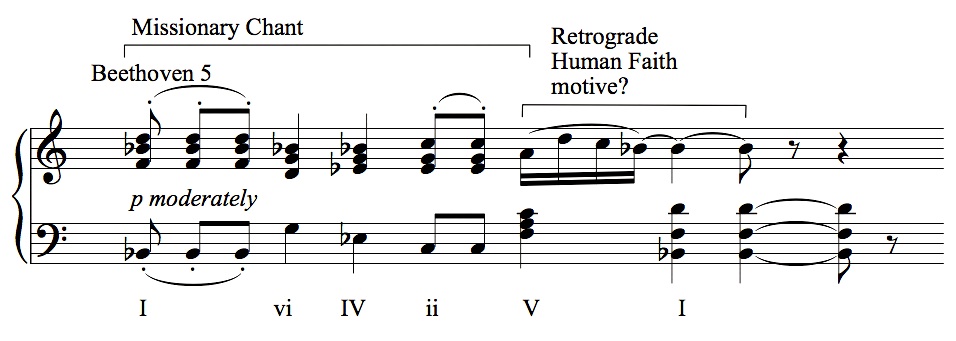

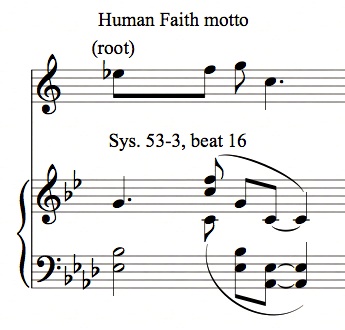

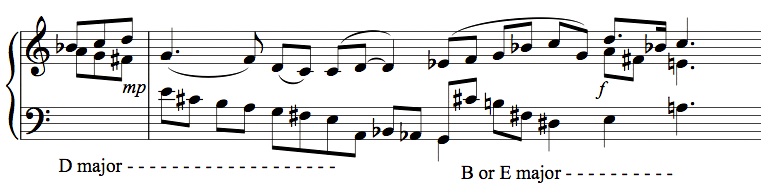

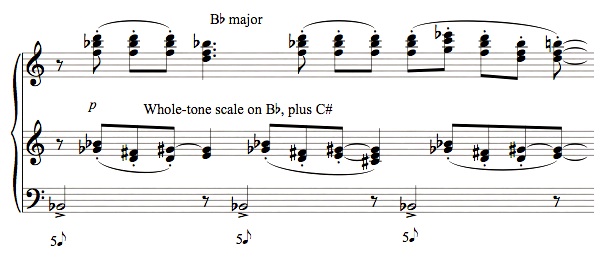

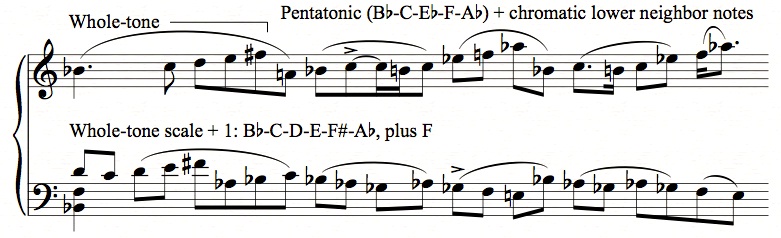

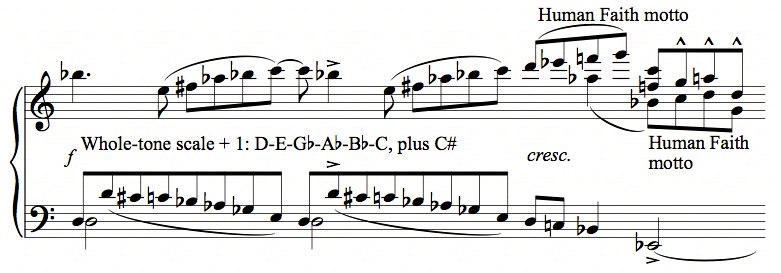

The advantage of 72 tones per octave (or as it’s known among the cognoscenti, 72tet – 72-tone equal temperament) is that it renders close approximations to some of the lower but still more exotic overtones not in common use. (Please excuse the theory for the moment, we’ll resume practicality next paragraph.) A cent is defined as one 1200th of an octave, and with a new pitch every 17 cents one can achieve pretty clean 7th, 11th, and 13th harmonics. In fact, despite his equal-step grid Sims makes it clear that overtones are what he’s generally aiming for. At least in most works, he typically selects notes from the 72 possible to form an 18-note scale based on the 16th through 32nd harmonics, with a few “tendency tones†to fill it out. The varied transpositions of this18-note scale ultimately necessitate all 72 pitches.

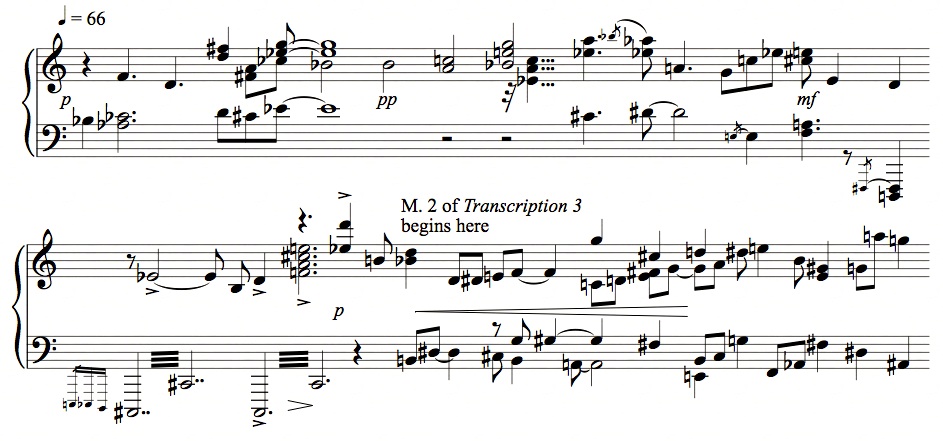

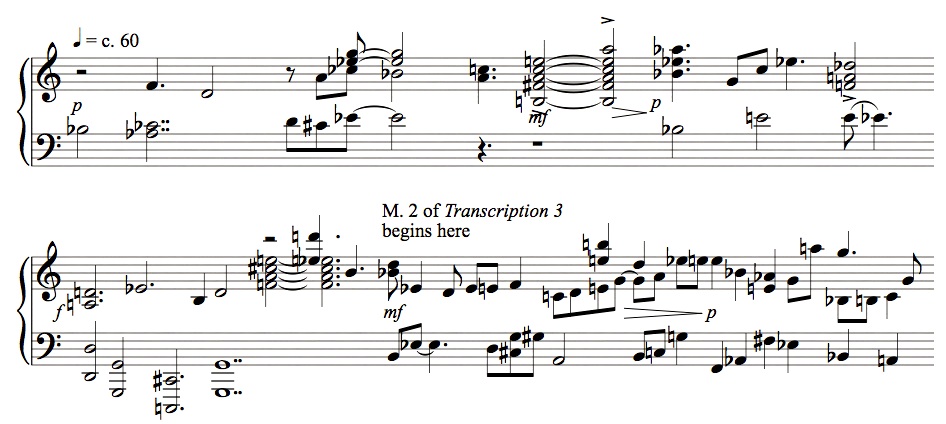

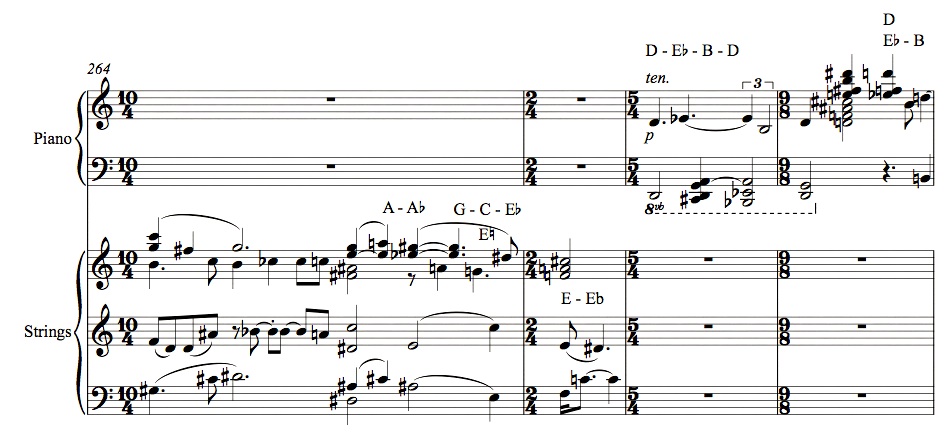

The advantage of the 72-tone system with its mere three extra accidentals, as the Bostonians love lecturing the rest of us, is its practicality for live performance (as opposed to Johnston’s notation with its open-ended accidental system and difficult-to-find perfect consonances). Every sixth pitch is a familiar one on the piano, and the rest can be interpolated via a regular system that requires little explanation. As a result Sims’s output consists primarily of chamber music, and he has a special penchant for combining winds and strings, and playing the strings and winds off against each other. Like his String Quartet No. 2 (1962), Musing and Reminiscence (2003) and Landscapes (2008) reprise the two-wind/three-string combination; his Sextet of 1981 is scored for clarinet, alto sax, horn, and three strings; Night Piece (1989) is for flute, clarinet, viola, and cello with a background computer tape; and there’s a Flute Quartet (1982) and Clarinet Quintet (1987). Sims also has some delightful piano music and choral music using only the usual 12 pitches (12tet), and some orchestral work, but it’s the small wind-and-string groups in which he brews his microtonal aesthetic.

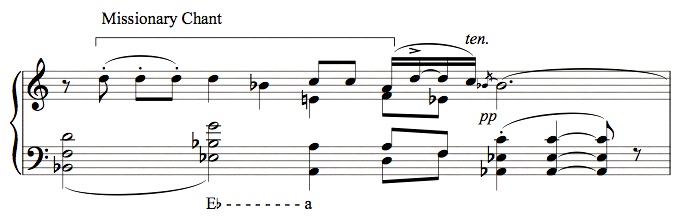

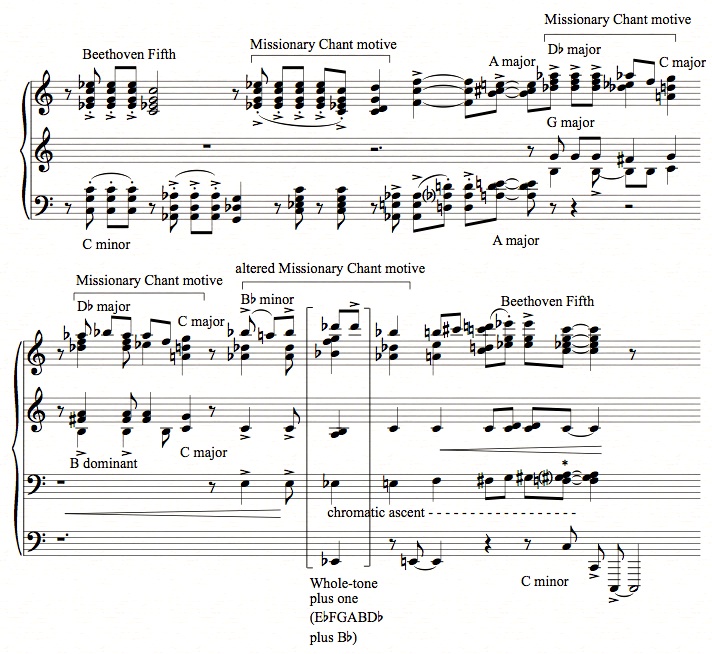

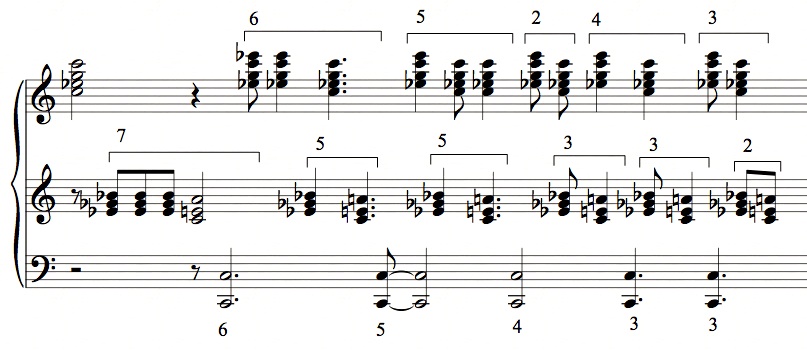

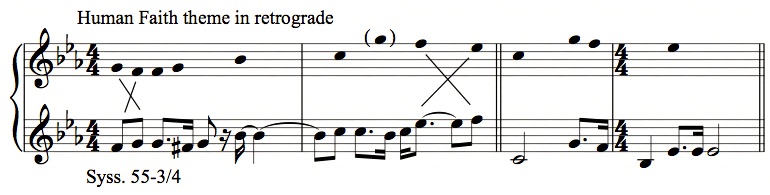

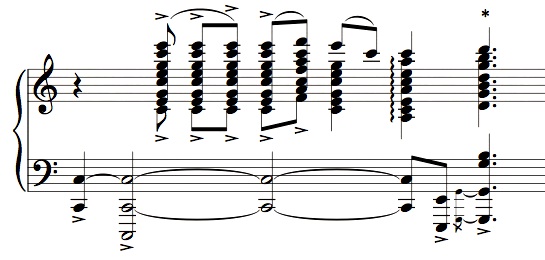

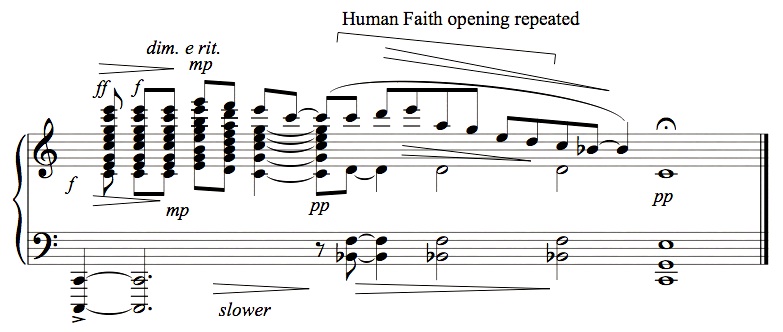

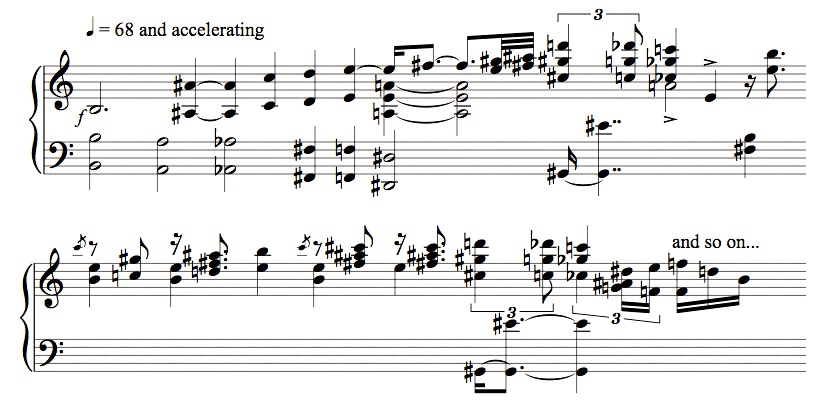

And a well-focused aesthetic it is. Sims tends to start off with a close set of pitches, often in repeated notes or in tremolo, whose evolution into wider and more complex harmonies evolves in accelerando. His music’s journey is always linear and easily followed by the ear – a wise thing, given the wild unfamiliarity of the ground he likes to cover. For some reason that psychologists will have to explain some day, composers who love splitting the half-step also love applying the same mathematics to rhythm, and Sims (much like Johnston) is fond of suggesting different tempos running at the same time. Quintuplets are everywhere, as well as fours-in-the-space-of-five. Tempos of fast movements run extremely fast, slow movements can be almost stationary. Between the 72 pitches and the phasing rhythms, it looks like extremely difficult music to play, but the types of difficulty are closely limited. So consistent is Sims’s language that I imagine once you learn to play one piece well, the others come much more easily.

For the listener, it’s a walk on the wild side indeed. The music is a pulsing, shifting continuum, dotted all round with contrapuntal echoes that maximize the tuning’s oddities. Yet if conventional moorings fall by the wayside, the music nevertheless projects a sense of restraint and logic. The microtonality comes off as exotic, yet the music’s linear motion and motivic cohesiveness keep the ear engaged. Music and Reminiscence opens with a series of parallel almost-fifths between the flute and clarinet, slightly changing in size. The first movement of Night Peace closes with a long, fluctuating drone on a wide tritone of 633 cents – bet you’ve never gotten to savor that ambiguity before. The music throbs, churns, dances, hibernates through pitch complexes you’ve never heard before, and the rhythm – though you’d rarely be able to identify a meter or locate a downbeat – has a pulse-based naturalness to it.

As with so much music that fascinates me, I regret having to describe Sims’s so technically. But it’s thoroughly abstract, with no programmatic associations, no typical musical forms, little melody in the traditional sense, no clear relation to minimalism or serialism or New Romanticism or heavy metal or polka or anything else. It’s just a unique brand of musical experience, and the only alternative to hearing it is describing how it’s made in hopes that you can imagine from that. And as Boston’s young microtonalists seep out across the rest of the country from the East Coast, the sense of Sims’s seminal influence is going national. He’s been one of our most original undergound musical legends for decades, and the mystery has built up too much pressure to keep quiet any longer. The good jokes he’s gotten off in his career are merely foils for realizing how serious and unprecedented his music is.