I have only made one edit on Wikipedia since I made a big brouhaha about the site several months ago. I ran across a page titled “Cultural depictions of George Armstrong Custer,” and noticed a subsection on musical references to Custer. Human nature being what it is, I rather thought a citation of my music theater work Custer and Sitting Bull might be appropriate there, and added it. It was immediately deleted, as violating the rules against self-promotion. I said “Hmph,” or words to that effect, cursed myself for deigning to pay attention to that benighted web site, and moved on.

Weeks later I get a note from the person responsible for the deletion. He (or she) has restored the reference, explaining that it is better for someone besides the composer to have added it in. He had also supplied, in his text, the helpful fact that Custer and Sitting Bull was premiered in New York in 2000, and asked me to verify the accuracy of what he had written.

Now, given Wikipedia’s philosophy, I am rather affronted to be appealed to to verify facts about my own career. Silly me, I had rather thought I premiered Custer and Sitting Bull in 1999 in Los Angeles, but clearly that impression is too subjective to be trusted. I have no printed reference work to footnote for the information, only my own resumé, which I could have all kinds of self-serving reasons to falsify. Perhaps I am trying to claim credit for having achieved in the 20th century innovations that didn’t really occur until the 21st. And so if Wikipedia’s stance is that information added by an objective party is always better than that added by a self-interested expert, then in the Wikipedia universe, Custer and Sitting Bull will have to have been premiered in New York in 2000. To ask my opinion in the matter seems like hypocrisy.

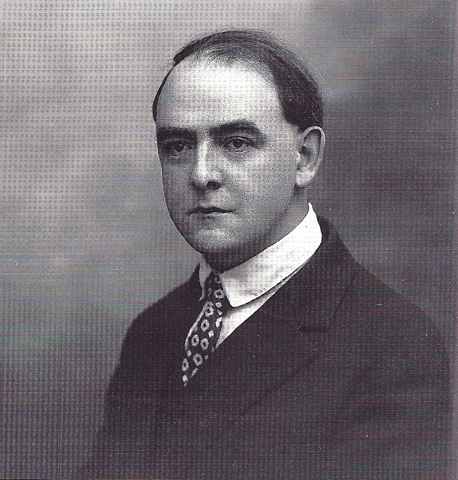

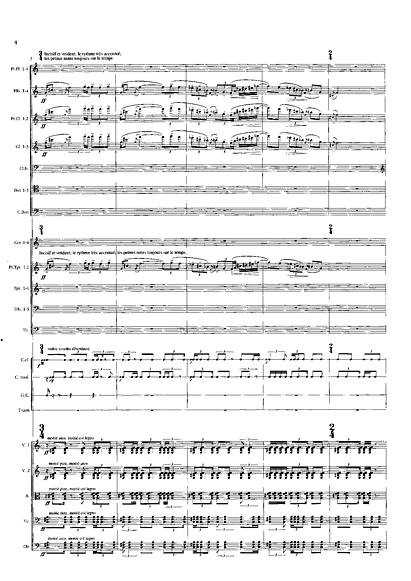

What I can do, though, is tell you about the most astonishing composer I learned about there: Matthijs Vermeulen. The Dutch call Vermeulen (1888-1967) “the Charles Ives of Holland,” and also their Varèse. He is the archetypal undiscovered composer. His Second Symphony – considered by many his most groundbreaking work (second page pictured below) – received its first performance in 1953, and Vermeulen himself first heard it in 1956. He had written it in 1920. The tone clusters, polyrhythms, percussion, and atonal counterpoint it opens with are easily as daring as anything Varèse would write in the next decade. To throw yet another comparison in, the Dutch refer to it as “the Dutch Sacre du Printemps.” Curiously modest about promoting their national composers, they won’t tell you anything about Vermeulen unless pressed, but if you mention how remarkable he was, they look proud as punch.

What I can do, though, is tell you about the most astonishing composer I learned about there: Matthijs Vermeulen. The Dutch call Vermeulen (1888-1967) “the Charles Ives of Holland,” and also their Varèse. He is the archetypal undiscovered composer. His Second Symphony – considered by many his most groundbreaking work (second page pictured below) – received its first performance in 1953, and Vermeulen himself first heard it in 1956. He had written it in 1920. The tone clusters, polyrhythms, percussion, and atonal counterpoint it opens with are easily as daring as anything Varèse would write in the next decade. To throw yet another comparison in, the Dutch refer to it as “the Dutch Sacre du Printemps.” Curiously modest about promoting their national composers, they won’t tell you anything about Vermeulen unless pressed, but if you mention how remarkable he was, they look proud as punch.

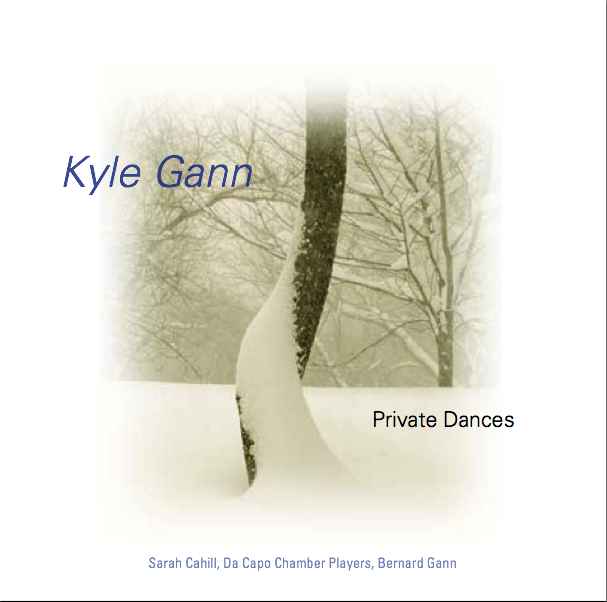

A copy of my new CD on the New Albion label, Private Dances, has just been handed to me. The official release date is January 22. My stuff never seems to get out quite in time for Christmas (this happened with Music Downtown two years ago too), but then, I’m not much for participating in American commercialism anyway. I guess.

A copy of my new CD on the New Albion label, Private Dances, has just been handed to me. The official release date is January 22. My stuff never seems to get out quite in time for Christmas (this happened with Music Downtown two years ago too), but then, I’m not much for participating in American commercialism anyway. I guess.