I insist that I am at least tied for the place of Number 1 Charles Ives fan on the planet, but I’ve done no scholarly work on his music; I hope to, someday, because I’m not really satisfied with what’s been written on my favorite piece the Concord Sonata. In general it is enough work just keeping up with what research is already out there. Someone mentioned that there are already 70 full-length books on Ives. Like flies to roadkill are the musicologists to Ives. Anyway, the point of a keynote address, as I see it, is not to present new information anyway, but to provide a rough general picture to be filled in with detail and variously repainted by the participants, which happened to this one. (For one instance, I mention below that many of Ives’s early songs could have been musically at home in the 1820s. Wesleyan musicologist Yonatan Malin admitted that this was true harmonically and texturally, but that the rhythms and style of text setting tend to be post-Wagnerian, which is not something that would have occurred to me.) It would be a luxury to be allowed to write one’s keynote speech after one’s understanding had been broadened by the conference, but a few people asked me to make this text available, so here it is: simply one composer’s reaction to the overall meaning of Ives’s songs.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Must a Song Always be a Song?

I like to think of Charles Ives sitting at home, after work, reading a newspaper. I don’t imagine anyone else we know about has ever read a newspaper the way he did. He’d see a little bit of verse in the New York Herald:

Quaint name,

Ann Street,

Width of same,

Ten feet.

Barnums mob

Ann Street,

Far from

Obsolete.

and ripping arpeggios leading to crashing chords would leap into his head. Or, reading a book by the Reverend James T. Bixby, called Modern Dogmatism and the Unbelief of the Age, he would run across a poem:

There is no unbelief.

For thus by day and night unconsciously,

The heart lives by that faith the lips deny.

God knoweth why!

and stern, puritan triads would swell into his ear, dying away into a wisp of the old Lowell Mason tune Azmon, “O, for a thousand tongues to sing / My great redeemer’s praise / The glories of my god and king, / The triumphs of his grace!” Near the surface of Ives’s consciousness swam a jumbled wealth of tunes and lyrics and symphonies and ragtime and college songs and complex sonorities and fearsome rhythms, any and all of which could be triggered by a well-envisioned image, a piquant phrase, a clever rhyme.

In the brief essay written to accompany the first printing of Ives’s 114 Songs, he tells us explicitly how he saw this process. He presents it as a theory that no one had ever agreed with before (except a man once who was trying to sell him a book called “How to Write Music While Shaving”). The theory runs thus:

[A]n interest in any art activity from poetry to baseball is better, broadly speaking, if held as a part of life, or of a life, than if it sets itself up as a whole – a condition verging, perhaps, toward… a kind of atrophy of the other important values….

[I]f this interest… is a component of the ordinary life, if it is free primarily to play the part of the, or a, reflex, subconscious-expression,… in relation to some fundamental share in the common work of the world,… is it nearer to what nature intended it should be, than if… it sets itself up as a whole – not a dominant value only, but a complete one? If a fiddler or poet does nothing all day long but enjoy the luxury and drudgery of fiddling or dreaming, with or without meals, does he or does he not, for this reason, have anything valuable to express? – or is whatever he thinks he has to express less valuable than he thinks?

This is stated with a humorously self-effacing circuitousness, and I’ve left out a number of intervening clauses that would render it unintelligible off the page, but the gist is Ives’s defense of relegating artistic creativity to the periphery of one’s life, rather than doing it, to put it bluntly, as a job. Ives’s belief as stated here is that music’s most valuable function is as a reflex subconscious expression – that the valuable part of music comes from the subconscious, and that the way to trigger it is to catch it inadvertently, almost by an accident of consciousness. Thus the unexpected inspiration of having musical sounds triggered by something you read in a newspaper is not only tolerated as a creative paradigm, but privileged, over the more self-conscious act of sitting down to write a symphony for which one has received a commission – whose inspiration is likely to be attenuated, contaminated, by, in Ives’s words, “the artist’s over-anxiety about its effect upon others.”

This absolute confidence in inspiration is a young man’s view of creativity. We think of Ives as a cranky old diabetic, easily over-exerted, waving his angry fist at planes flying overhead, and it’s always a shock to realize that when he wrote these words he was 47, the same age that the enviably buff Barack Obama is now – and that his creativity had already been in decline for several years. Within the typology outlined in David Galenson’s book Old Masters and Young Geniuses, Ives was a “Conceptual Innovator” rather than an “Experimental Artist.” That is, he composed quickly, guided by a predetermined sense of what he heard in his head, rather than slowly working his materials and proceeding intuitively, without any preconceived idea for where the music was heading. According to Galenson’s researches, the conceptual innovators tend to peak earlier in life than the experimental artists, in their 20s or 30s rather than their 40s or 50s. Of course Ives wrote Thanksgiving, one of his greatest works, at age 30, completed most of his great works, including the Concord Sonata, by his 41st birthday, and was almost through composing by age 44. The conceptual innovators, Galenson notes, also tend to be fond of quotation, T.S. Eliot’s The Wasteland being one of his prime examples.

However, this merely relativizes rather than answers Ives’s assertion, that the value of music is its ability to reflect back subconscious insights from one’s larger life when caught unawares. We know that Ives’s music was often incited by external stimuli, like a parade on the 4th of July or a Yale-Princeton football game or a crowd’s reaction to the sinking of the Lusitania. But fittingly, since he advances this theory in the “Postface to 114 Songs,” it is in the songs that we see the process spread out in its greatest variety. Only in the early songs written at Yale under Horatio Parker do we get the feeling that Ives sat down to write a song and looked around for a text. More often we get the feeling that he was struck by a text, sometimes just a chance line or two, or even just that an observation occurred to him that seemed to demand musical exegesis. Some of the texts reflected in Ives’s subconscious responses seem particularly trivial, fragmentary, or ephemeral. One of the bits of poetry Ives ran across in the New York Evening Sun was by one Anne Timoney Collins:

My teacher said us boys should write about some great man,

So I thought last night ‘n thought about heroes and men that had done great things.

If we look up Anne Timoney Collins on the internet today, every single reference to her is a reference to this Charles Ives song. Other than that she seems to have disappeared. Some of the more reckless record liner notes go so far as to say that she “flourished” in the 1920s. By “flourished,” they mean, apparently, that she got this poem printed in the New York Evening Sun. Whatever else her flourishing might have consisted of, we can only surmise.

Ives wrote many songs on poems and texts of famous authors: Bulwer-Lytton, Christina Rossetti, the Irish poet Thomas Moore, George Meredith, Alfred, Lord Tennyson, Heine, Shelley, Wordsworth, Shakespeare, Kipling, Longfellow, Goethe, Whittier, Byron, Keats, Robert Louis Stevenson, Robert Underwood Johnson, Vachel Lindsay, Thoreau, Whitman, Milton, Emerson, Browning, Matthew Arnold, Louis Untermeyer, Walter Savage Landor. After these comes a second rank of writers: ministers, hymnists, poetasters, such as Frederick Peterson, the Anglican minister Rev. Henry Francis Lyte who wrote “Abide with me,” the English clergymen Greville Phillimore and Henry Alford, the English statesman John Bowring, the religious poet Elizabeth York Case, the 18th-century bishop and ballad collector Thomas Percy. There are also a number of early songs written to texts found in previous songs of famous composers: Brahms, Dvorak, Schubert, Massenet, Robert Franz.

Ives set a poem by a friend from Yale, Moreau “Ducky” Delano, one by former Yalie Henry Strong Durand, and two by his poet friend Henry Bellaman. We know that the early American novelist James Fennimore Cooper had a grandson of the same name because the latter, who graduated from Yale in 1913, wrote the poem that Ives’s song “Afterglow” is based on. And of course, Ives wrote at least 40 of his songs on texts of his own, another eight we know of on poems by his wife Harmony.

What is remarkable about this miscellany of texts is that, if we divide them according to category – notable poets, clergymen and hymn writers, friends, wife, himself, odd bits of reading he ran across – there is little parallel division among the multifarious types of song. A poem run across in the newspaper, like “The Greatest Man,” might produce a major, fully fleshed out song, while a quotation from one of Ives’s most admired writers, like Emerson, might elicit a quizzical little fragment like “Duty.” If we separate out the songs for which Ives wrote his own texts, there is no apparent distiction between those and the others, they do not seem more personal. Almost every text Ives used was a quotation expressing his own thoughts.

Ives was no great respecter of texts even by famous authors, selecting and omitting lines to turn a poem into a song, or simply taking for his use the fragmentary thought that appealed to him. Similarly, he felt just as free to quote Whitman, Virgil, or a hymn in a text of his own. The effect of this lack of distinction, between famous poets and popular ones, between his own words and those of others is, as the late great Wiley Hitchcock pointed out in his “Charles Ives as Lyricist” article, that the persona we encounter in the songs is almost always Ives’s own. Only in a few of the early songs does one feel that Ives has put himself in the poet’s place, tried to hear the world through the poet’s ears, and altered his own style to fit the poem. Sometimes the text just as much as the music seems like a reflex subconscious expression, as in the song “Resolution”:

Walking stronger under distant skies,

Faith e’en needs to mark the sentimental places;

Who can tell where Truth may appear, to guide the journey!

This little song has no beginning, middle, or end. Its reiterated chords define no territory large enough to define a musical language. It seems a fragment of music, cut off from the total fabric of Ives’s imagination. In eight little measures lasting 25 seconds it leads to a dissonant but diatonic climax chord, then back to the opening thirds just enough to suggest a small circle, a bit of eternity without beginning or end. It is not a song, but less than a song, and therefore more interesting than a song because, not being self-contained, it points to a world beyond itself of which it is merely an evocative moment. Though it is titled “Resolution,” and speaks of resolve, it denies resolution. I’ve never been able to fathom what the text means. “Faith even needs to mark the sentimental places”? It is like an epigram from Nietzsche, or some classical author that speaks volumes only if we know its original context, which sadly is lost to history.

Or this one:

A sound of a distant horn

O’er shadowed lake is borne,

My father’s song.

This isn’t a song either, but a thought set to music. Since we know that Ives’s father was a decisive musical influence on him, and that he died suddenly after Ives went off to college, the text bears an immense emotional weight: but that weight isn’t generated or even alluded to in the song, except in the tiny pathos of the piano repeating the voice melody in canon, like an echo, perhaps Ives thinking of himself echoing his own father in canon. “Remembrance,” as these nine little measures are called, isn’t a song, but a cut-off bit of Ives’s life and mind that points us back to the whole of it.

And how many composers would have taken out manuscript paper to embroider such a trivial musing as “Why doesn’t 1, 2, 3, seem to appeal to a Yankee as much as 1, 2?” When I was in high school, the idea that a song could be this short came as such a revelation that I wrote a setting for chorus and large orchestra of a poem by Ogden Nash which read, in its entirety, “The lord in wisdom made the fly / And then forgot to tell us why.” The piece lasts 13 seconds, and is still waiting for its premiere.

So many of Ives’s songs can hardly be understood on their own, without reference to some larger musical vision of which they are a part. What is the song “Thoreau” except a footnote to the Concord Sonata? How would we understand its music, its chant-like vocal part, without recognizing the original? “The Night of Frost in May” is one of Ives’s loveliest conventionally tonal parlor songs. But what sense does its text make outside of the George Meredith poem from which it is excerpted? Meredith begins by describing sounds he hears in the woods on a frosty night in May:

Then soon was heard, not sooner heard

Than answered, doubled, trebled, more,

Voice of an Eden in the birdÂ

Renewing with his pipe of four

The sob: a troubled Eden, rich

In throb of heart: unnumbered throatsÂ

Flung upward at a fountain’s pitch,

The fervour of the four long notes,

That on the fountain’s pool subside,

Exult and ruffle and upspring:

Endless the crossing multiplied

Of silver and of golden string….Â

And then come the concluding words that Ives imposed on a melody earlier meant for another lyric, which, to be understood, need to be read in the rhythm as punctuated in the poem, rather than the phrasing imposed by the regular phrases of the song:

Then was the lyre of earth beheld,

Then heard by me: it holds me linked;

Across the years to dead-ebb shores

I stand on, my blood-thrill restores.

But would I conjure into me

Those issue notes, I must review

What serious breath the woodland drew;

The low throb of expectancy;

How the white mother-muteness pressed

On leaf and meadow-herb;

Know that background, and then this lovely little parlor song, otherwise rather enigmatic, takes on a mystical and truly Romantic fervor. Ives’s songs are a window backward into his education as an English major at Yale. Most of his poets were born in the 18th or early 19th century – as Wiley points out, he almost never set a poet younger than himself, and, perhaps prejudiced by Henry Cowell, Ives called Gertrude Stein “Victorian without the brains,” and an unfortunately typical example of modernity. Thus despite the modernism Ives created in his harmonies and rhythms, moving up to the very edge of 12-tone music and serialism in his song “On the Antipodes,” the overall picture his songs give us is of an American and English spirituality of the previous two centuries, reflected in a modernist subconscious.

This unsupported disparagement of Gertrude Stein in the Memos has always stuck in my mind, and when I was young it prejudiced me against her for many years. I see it as a possible reaction formation, a defense mechanism, against a seemingly unmanly tendency toward which Ives was irresistibly drawn. The most obvious distinction within Ives’s songs is that between early and late, early Romantic and Modernist. The “early” songs, not all of them that early, are almost neoclassic, Schubertian, pre-Wagnerian, in shape: consistent in texture throughout, with no more than a high note or a slight ritard to mark a final cadence. We might mention “Slow March,” “Canon,” “To Edith,” “My Native Land,” “Allegro,” “A Night Song,” “Kären,” “There Is a Lane,” “Ilmenau,” and quite a few others. Fabulous songs, every one of them inspired, every one impressing you with the initial attractiveness of its musical idea, but mostly rather conservative by contemporary European standards. Several of them would have felt just as much at home in the 1820s as they did 70 years later.

Among the modernist songs there are several archetypes, and several songs that follow no pattern but their own. But there is one archetype that strikes me as more central than the others, embodied as it is in more songs: the quiet texture of ostinatos suggesting eternity or an unchanging state, punctuated at the end, or near the end, with a climactic dissonance or set of dissonances, but returning at the end to the opening texture, somewhat circularly. We hear this most eloquently in “The Housatonic at Stockbridge,” where the dissonant white-note thirds over a C#-major drone create an image of a river flowing steadily, forever, immutable, until the text becomes more subjective at the end with the words “I also of much resting have a fear,” and the music speeds up to a climactic chord on B-flat, A, and D triads all at once – only to give away to some ppp chords suggestive of the beginning again.

We hear it in “From the Incantation,” where the ostinato is in the voice line, the atonality giving away to tonal chords at the climax, then ending quietly with the opening motive. We hear the circular form in “Resolution,” which returns to the beginning after its one climactic polytonal chord. It is suggested in “The Indians,” in which a sad repeating phrase works its way up to a rhythmically complex climax and then ends with the repeating phrase again.

The most obvious examples of this ostinato technique used to suggest eternity are two of Ives’s most popular songs. In “The Cage,” from 1906, a phrase repeated three or four times represents the repetitive pointlessness of a leopard’s life walking back and forth around a cage. The music builds to an unrepetitive climax on the words “A boy who had been there three hours began to wonder” – once again, as in “The Housatonic at Stockbridge,” suggesting that the unchanging ostinato represents nature and the climax some subjective point of human consciousness.

And in one song Ives managed to do without the climax altogether. I mean, of course, “Serenity,” the song which most explicitly embodies Ives’s sense of a song as a timeless piece of eternity. The two chords between which this song rocks back and forth for three minutes could have occupied Arvo Pärt for a full half hour. The poem by Quaker abolitionist poet John Greenleaf Whittier finds Zen in its Christianity:

O Sabbath rest of Galilee!

O calm of hills above,

Where Jesus knelt to share with Thee

The silence of eternity

Interpreted by love.

Drop Thy still dews of quietness

Till all our strivings cease

Take from our souls the strain and stress

And let our ordered lives confess

The beauty of thy peace.

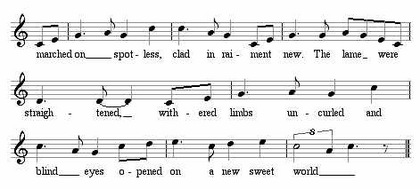

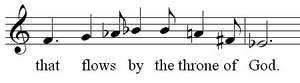

The two flat-five chords that bring the song to an arbitrary close have a purely conventional function of stopping the song. They’ve always disappointed me, because the song could go on forever, like Tibetan or Gregorian chant, and I want it to. We find a similar stillness expressed by the same wandering around over a few notes in “General William Booth Enters into Heaven” when

Jesus came from the courthouse door,

Stretched his hands above the passing poor,

Booth saw not, but led his queer ones,

Round and round and round and round…

On the other hand, an earlier passage in the same song exhibits a nervous wandering within a whole-tone scale similar to that of “The Cage”:

Every slum had sent its half a score

The round world over (Booth had groaned for more).

Clearly for Ives this archetype of repetitive ostinato with a closely circumscribed melodic line demonstrated eternity in two potential aspects: one spiritual and peaceful, the other evocative of boredom and frustration, suitable for the tiger whose strivings haven’t ceased.

Recently I was listening to “Sunrise,” Ives’s last song from 1926, the one with the violin. My mind wandered for a moment, and when it came back I found myself wondering why I was listening to Morton Feldman – because the reiterated figures and sparse, repeating single notes of that piece seem to point to Feldman’s motionless, mobile-like sonority clouds of half a century later. It’s as though Ives foresaw not only the new materials and rugged contours of modernism, but also the allure of the static, spiritual quality of repetition and phase-shifting that would emerge once the main wave of modernism had passed. Only in that one song, “Serenity,” did Ives so yield to the spiritual impulse that he omitted the climax, the element of human consciousness.

Clearly, for Ives repetition, and especially rhythmically dissonant, out-of-phase repetition, meant what it has meant for the minimalists, a kind of meditation on eternity. If indeed Ives had read any Gertrude Stein, instead of merely knowing her reputation through Cowell, I wonder if he recognized in her flat, repetitive, climaxless, minimalist prose a seductive element of stasis and repetition that he was too afraid would take over – as perhaps it finally did, in the long polytempo prelude of the Universe Symphony, whose completion he never acknowledged. Or perhaps he simply didn’t find in Stein the spirituality that he felt justified the stasis. Of course, human music cannot truly represent eternity, and so every musical evocation of eternity becomes a mere fragment, lacking a true beginning or ending and pointing beyond its double barline. “Serenity” is not the only Ives song that sounds like it could continue past its ending.

Another respect in which Ives’s songs point beyond themselves is worth mentioning. There is, as we all know, a secondary language within Ives’s music, a language of hymns and patriotic tunes, that makes it especially potent for those of us who spoke that language from birth. If you know that language, you can register the pun at the end of “Religion” whereby “O for a thousand tongues to sing” turns into “Nearer my god to thee,” so slyly that the unconscious notices before your conscious can work out the resemblance. I know a lot of people who have spent their careers on Ives’s music are from the South like myself, and those of us who grew up in the South may have imbibed that language of hymns more recently and as a living tradition than some of our urbanized Northern neighbors. For instance, there are some songs that Ives quotes that I didn’t grow up with – “Marching Through Georgia,” commemorating Sherman’s march to the sea, never became very popular in Dixie – and I had to learn the associations of those songs, when Ives quotes them, as an adult. Therefore they don’t grab me in the gut the way “There is a fountain filled with blood” and “Just as I am” do.

“Just as I am,” its undistinguished tune notwithstanding, was the most emotion-filled hymn in the Southern Baptist Church, the one the choir sang at the end of every service when Dr. Criswell invited people to come down to the front of the church to be saved. No matter how far I travel culturally from that experience, no matter how indignant I was about Rick Warren praying at the inaugural, when Ives’s song “The Camp-Meeting” turns into “Just as I am” at the end, the reptile part of my brain will transport me, involuntarily, back into that milieu, and I’ll see you again when the song is over.

This second language grants Ives the ability to make the tune say one thing and the words say something else, as when, in “General William Booth,” the words say [to my own astonishment I sang the following examples, something I don’t usually do in public],

But at the same time the melody says,

There is a fountain filled with blood

Drawn from Emmanuel’s veins

And sinners washed beneath that flood

Lose all their guilty stains.

even though Vachel Lindsay directed that the poem should be sung to the tune of a different hymn, “Are You Washed in the Blood of the Lamb,” which has a completely different syllable scheme. I’m not sure those are the right words to that hymn, but I sang it many times in the first 20 years of my life, and I decided to set it down as Ives would have, from memory, with whatever divergences from the printed page it may have acquired in 30-odd years. It is difficult to overstate the subconscious pull that even only two or three notes tugging on a childhood memory can have in Ives’s music.

And incidentally, I will never cease to marvel at how Ives correctly intuited that “Shall We Gather at the River” was intended, from time immemorial, to cadence through a diminished triad:

– a version that has completely supplanted the original in my memory.

It may appear a criticism of some of Ives’s songs to say that they don’t stand on their own, but it’s actually to their fragmentary character that I attribute some of their psychological power. There is a theme in Shakespeare criticism, brought out most articulately by Stephen Greenblatt, that starting in the year 1600 Shakespeare heightened his sense of drama by omitting rational motivation from his plots. For instance, in the original Danish legend of Hamlet, it is no secret that Claudius has killed Hamlet’s father, and therefore Hamlet has a very practical reason to feign madness – to convince his uncle Claudius that he’s harmless and thus keep himself from getting killed. But Shakespeare makes the murder of Hamlet’s father a secret that Claudius doesn’t realize Hamlet knows, and therefore Hamlet’s simulation of madness has no practical motivation. The irrationality of it draws us more deeply into the play because the plot doesn’t explain why he’s doing it.

In a similar way I think some of Ives’s less self-contained songs ultimately make a more vivid impression because they are not explainable within themselves, and make our imaginations roam elsewhere. We’ve all seen his most complete songs, like “General William Booth,” “The Greatest Man,” “Majority,” or “The Side Show” printed in anthologies as an example of a great 20th-century song, and it always strikes me as a little disappointing, even misleading, because the breadth of Ives’s genius is so panoramic that one little perfect song, even one so ambitious as “General William Booth,” reduces him to a type, as though he were just another Dvorak, or Mussorgsky, or Bartok, that you could distill the essence of his style to one example. But a song like “Afterglow,” or “Walt Whitman,” or “Religion” or “Maple Leaves” or “Disclosure” or “Grantchester,” can’t be anthologized because it would raise more questions than it answers, and can’t be reduced to a type. Each of those songs is too obviously a cut-off piece from some larger whole, and needs the rest for context. These unanswered questions make us continue pondering some of these more ambiguous songs long after we would have quit thinking about “The Side Show.”

But this fragmentation manifests not only in the texts. Even more deeply it stems from radical discontinuities in the music, such as the atonally impressionistic introduction of the song “Old Home Day,” which gives way to an innocent opera house tune in march time – and never returns. Or the few syrupy measures of C major in the middle of “On the Antipodes,” surrounded otherwise by massive 12-tone sonorities in formalist patterns. Or the grandiosely Romantic chords that suddenly end the otherwise straightforward song “In the Alley,” or, in the opposite direction, the suprise V-I cadence in which the atonal song “Duty” crashes to a close. Each of these disjunctions points beyond the boundaries of the song to a world of musical materials, in some cases a foreign syntax, which is not instantiated within the song itself. The material of the song partakes of two or more different worlds, and we have to look outside the song to those worlds to complete the meaning of the song in our minds. This is, after all, classic postmodernism, and the premier theorist of musical postmodernism, the late Jonathan Kramer, took Ives’s music as the earliest locus classicus for the tendency.

When Ives wanted to imitate a pre-existing style, he could do so remarkably well. I’ve always been astonished at how succulently and identifiably French his songs “Qu’il m’irait bien” and “Chanson de Florian” are, yet without being traceable to any specific French composer. Yet this is rare for him, and more than any of the later postmodern composers, like William Bolcom or David Del Tredici or George Rochberg or even John Zorn, Ives had to create the musical worlds he refers to in his fragmentary works, so that in the Concord Sonata, “General William Booth,” Three Places in New England, and other works we find the completion of these other musical languages. In this way, it seems obvious that, more than any other great song composer, Ives’s songs need to be presented in their entirety for their sense to be complete, so that this week’s marathon serves a more urgent purpose than could any marathon of Schubert or Hugo Wolf or Ned Rorem or Cole Porter. Every single song is a piece of a puzzle.

As Ives says more than once in the “Postface to 114 Songs,” the question of whether one’s artistic creativity will gain more depth being in the center of one’s life rather than on the periphery is one that every composer has to answer for him- or herself. Many of us are not given the choice to make. Ives intended his songs as a reflex subconscious expression in response to the things in life that triggered his imagination, and what is most amazing about him for me is the compelling verisimilitude with which he appears to succeed in this. Where every previous composer had channeled his imagination through chords and materials consciously learned and analyzed from previous music, Ives invented not only a language, but languages, in which to express his subconscious – the atonal and massively contrapuntal language of “From Paracelsus,” the language of tone clusters in “Majority,” the dissonant tonal language of “The Housatonic at Stockbridge,” the 12-tone language of “On the Antipodes.”

For me, and I have never qualified this opinion, Ives was the greatest composer who ever lived – precisely because of his preternatural ability to imprint his imagination onto the musical page intact in every detail, without compromise, without a filter, without limitations, without fear, without invoking a syntax where no syntax was needed, without the slightest curtailing of the emotional intent for the sake of a merely aesthetic effect. Of course, this makes him Platonic rather than Aristotelian, because it was Plato who insisted on absolute fidelity to reality, Aristotle who argued for the internal consistency of a work of art. There will always, I suppose, be Aristotelians who find Ives lacking in aspects of completeness and craftsmanship and consistency of language, but I hope I have suggested that in his case these criticisms are inapplicable, and that the deepest power of his music resides exactly in what a conventional viewpoint would consider his flaws. That’s the spin I’d like to have in the air this week as we embark on listening to all 185 of these wonderful, inspired, and unbelievably varied songs.