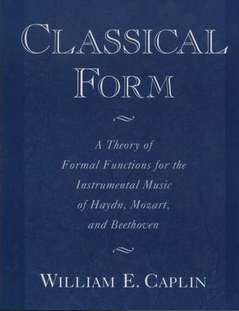

In my pedantically wonkish way, I’m excited to be teaching my sonata-form classes with William E. Caplin’s book Classical Form (Oxford, 1998), as I have been for several years now. For those who don’t know it, Caplin went through the complete sonata-form works of Haydn, Mozart, and Beethoven, and catalogued everything that happens in all of them – what theme the development starts with, what relative keys get referred to in the codas, and like that. I don’t use the book as a textbook: even though Caplin’s writing style is admirably clear, it’s too dense and dependent on hundreds of examples, and to tell the truth, I’ve never yet gotten through the whole thing myself. Read four paragraphs and your eyes glaze over from the amount of detailed information you’re trying to take in. (I once talked to someone at Oxford about how useful an undergrad-friendly version of the book would be, and she told me one was being contemplated.) But I’ve outlined chapters for my students as a kind of flowchart for what’s possible in sonata form, and it’s made it feasible to teach the subject honestly. I think when I was in school I was given some kind of “typical” sonata form chart (if indeed we ever paid any attention to any music before Webern, which I don’t specifically recall doing), from which, of course, every sonata we ever looked at – deviated. But Caplin offers a descriptive plan rather than a prescriptive one. So yesterday in class we went through the outline, and then through movement 1 of Beethoven’s Op. 2 No. 3 – and every move Beethoven made was one of the possibilities in the Caplin-based flow chart. One student, who had apparently gotten a whiff of the old prescriptive-style training, asked, “Can we look at a typical sonata first, one that follows all the rules?” And I said, “There’s no such thing as a typical sonata. Might as well ask me to go out on the street and bring in a typical person.” Instead of having to explain why every piece we listen to is an exception to most of the rules, I can teach the whole conception of sonata form as a range of possibilities and, better yet, meanings, some of which get chosen for identifiable logical or expressive reasons. It’s nice to have one theoretical subject I can teach without making excuses for the lameness of the pedagogy. (Sometimes we look at Clementi, Dussek, and Hummel, too, and find some possibilities outside Caplin’s range.)

In my pedantically wonkish way, I’m excited to be teaching my sonata-form classes with William E. Caplin’s book Classical Form (Oxford, 1998), as I have been for several years now. For those who don’t know it, Caplin went through the complete sonata-form works of Haydn, Mozart, and Beethoven, and catalogued everything that happens in all of them – what theme the development starts with, what relative keys get referred to in the codas, and like that. I don’t use the book as a textbook: even though Caplin’s writing style is admirably clear, it’s too dense and dependent on hundreds of examples, and to tell the truth, I’ve never yet gotten through the whole thing myself. Read four paragraphs and your eyes glaze over from the amount of detailed information you’re trying to take in. (I once talked to someone at Oxford about how useful an undergrad-friendly version of the book would be, and she told me one was being contemplated.) But I’ve outlined chapters for my students as a kind of flowchart for what’s possible in sonata form, and it’s made it feasible to teach the subject honestly. I think when I was in school I was given some kind of “typical” sonata form chart (if indeed we ever paid any attention to any music before Webern, which I don’t specifically recall doing), from which, of course, every sonata we ever looked at – deviated. But Caplin offers a descriptive plan rather than a prescriptive one. So yesterday in class we went through the outline, and then through movement 1 of Beethoven’s Op. 2 No. 3 – and every move Beethoven made was one of the possibilities in the Caplin-based flow chart. One student, who had apparently gotten a whiff of the old prescriptive-style training, asked, “Can we look at a typical sonata first, one that follows all the rules?” And I said, “There’s no such thing as a typical sonata. Might as well ask me to go out on the street and bring in a typical person.” Instead of having to explain why every piece we listen to is an exception to most of the rules, I can teach the whole conception of sonata form as a range of possibilities and, better yet, meanings, some of which get chosen for identifiable logical or expressive reasons. It’s nice to have one theoretical subject I can teach without making excuses for the lameness of the pedagogy. (Sometimes we look at Clementi, Dussek, and Hummel, too, and find some possibilities outside Caplin’s range.)

A Couple of Complaints

I’m not a critic anymore, and don’t want to be one. But I am bothered by a couple of things lately, and hope that a word to the wise won’t be resented. (Like anything I say ever goes unresented by a lot of people.) I will, at least, refuse to specify what music I’m talking about.

How Music Sounds to Children

I hadn’t listened to Schubert’s Fifth Symphony in far too long, and I did today. I have a special relationship with that piece – or rather, it has one with me. It was one of the pieces I heard on recording from my first weeks out of the womb. I knew how it went before I could talk. And whenever I play it, I’m transported into feeling like I’m a child hearing music again, as something magical and captivating that I can’t figure out. It links me to a preverbal relationship with music, and reminds me, in a way unlike any other work, of how music must sound to people who can’t read it. There are other works that I was familiar with as early, such as Mozart’s D Minor Piano Concerto and his D Major Piano Sonata K. 576, but those I’ve analyzed many times with classes, and the spell has been broken. I have intentionally never cracked a score to Schubert’s Fifth. I can’t quite picture how it’s notated – I could figure it out, but don’t want to. There are even syncopations in the first movement where I’m not sure where the downbeat is. I hear that flute obligato joining the main theme and I’m instantly in another world, safe and secure, and nothing bad has ever happened. It’s an almost entirely right-brain experience (though there are still passages where I can’t keep the phrase “flat submediant” from leaping into my left brain). Someday before I die I want to open a score of the Schubert Fifth and break the spell, but I’m in no hurry. I feel like something about still having that experience intact helps keep me honest in my own composing.Â

Taruskin Distilled

The grim history of the twentieth century – something Brahms or Franck could never have foreseen, to say nothing of Matthew Arnold or Charles O’Connell – played its part as well both in discrediting the idea of redemptive culture and in undermining the authority of its adherents. The literary critic George Steiner, one such adherent, after a lifetime devoted (in his words) to “the worship – the word is hardly exaggerated – of the classic,” and to the propagation of the faith, found himself baffled by the example of the culture-loving Germans of the mid-twentieth century, “who sang Schubert in the evening and tortured in the morning.” “I’m going to the end of my life,” he confessed unhappily, “haunted more and more by the question, ‘Why did the humanities not humanize?’ I don’t have an answer.” But that is because the question – being the product of Arnoldian art religion – turned out to be wrong. It is all too obvious by now that teaching people that their love of Schubert makes them better people teaches them little more than self-regard. There are better reasons to cherish art.

– Richard Taruskin, Music in the Nineteenth Century, p. 783

Classical Obsession

We went to Concord, Mass., a couple of weeks ago. It’s my default short-vacation spot. I love the bookstores: The Barrow, the Concord Bookshop, Books with a Past, as well as the gift shops at local museums and authors’ houses. I always find a dozen books there I didn’t know about, many about Transcendentalism. And we walk around Walden Pond, and I wonder how much quieter it might be if Thoreau hadn’t turned it into such a shrine.Â

In The Barrow, I was going through

poetry, and my eye ran across a title: Sonata Mulattica. I did a double take,

chuckled in surprise. I tried to keep going. I looked at it again. I took it

out, read a poem, put it back and moved on. But the book virtually leapt back

into my hands. It’s by Rita Dove, African-American poet who was poet laureate from

1993 to 1995. How can it be that the national poet laureate receives so little

fanfare that I can fail to have heard of her 15 years later?

Anyway, Sonata Mulattica is an entire book of poems about a single subject: Beethoven’s writing the Kreutzer Sonata

for the “African prince” violinist George Augustus Polgreen Bridgetower,

falling out with him over a woman, and then dedicating the piece to Rodolphe

Kreutzer instead. Dove uses lots of musical terminology, all correctly – in youth she

played the cello, apparently – and her characterizations ring true and tired

and humble, with none of the pompous mythologizing that attends portraits of

great composers. Poem after poem after poem on this one moment in history, some

from Bridgetower’s perspective, some from Beethoven’s, some from that of minor

characters, and some of my favorites are about Haydn, who encouraged Bridgetower. This one is titled Haydn, Overheard (I’ll refrain from entire poems for copyright reasons):

It is a sad thing alwaysÂ

to be a slaveÂ

but if slave I must, betterÂ

the oboe’s clarion tyranny

than a man’s cruel whims.Â

I stayed on at Esterhaza,Â

writing music for the worldÂ

between spats and budgets,

with no more leaveÂ

to step outside the gatesÂ

than a prize egg-laying hen.Â

Even after Miklós died

and his tone-deaf sonÂ

filled the courtyardÂ

with military parades,Â

I hesitated: Call it

robbing Peter to pay Paul,Â

but I had been homeless onceÂ

and did not care for hunger….

But the finest gift I ever receivedÂ

was the vision of Johann Peter SalomonÂ

with his flamboyant nose and capeÂ

swirling across my doorstep:

“I’ve come to fetch you,” he said.Â

It was December. We set outÂ

from Vienna on the fifteenthÂ

for London, that great free city.

And here’s Bridgetower, in a poem called Andante con

Variazioni:

Thank you. It was a privilege. You are so kind.Â

It is all his doing; I am merely the instrument.Â

To have the honor of this premiere…Â

a beauty of a piece, indeed.

What an honor! Countess, I am enchanted.Â

I only wish I could better express my gratitudeÂ

in your lovely language: Vielen Dank.Â

It is all his – why, thank you, sir, I am speechless….

Herr van Beethoven is indeed a Master, and Wien

an empress of a city. My apologies –

I only meant that she is… magnificent.

(Ludwig, get me out of here!)

[UPDATE: In an attempt to better do the book justice, here’s Beethoven:

Call me rough, ill-tempered, slovenly – I tell you,

every tenderness I have ever known

has been nothing

but thwarted violence, an ache

so permanent and deep, the lightest touch

awakens it… It is impossibleto care enough. I have returned

with a second Symphony

and 15 Piano Variations

which I’ve named Prometheus,

after the rogue Titan, the half-a-god

who knew the worst sin is to take

what cannot be given back.I smile and bow, and the world is loud.

And though I dare not lean in to shout

Can’t you see that I am deaf? –

I also cannot stop listening.]

It’s a lovely book, a theme with variations indeed, and from

every possible perspective. I could imagine reading about this episode and

writing a poem, but an entire book of poems and so musically intelligent – it’s

quite astonishing. I considered ordering it as a textbook for my Beethoven

course this fall, but I think I’ll just put it on reserve, and make a much

bigger deal than usual about the Kreutzer Sonata, which is one of my favorite

middle Beethoven pieces anyway. Rita Dove: Sonata Mulattica (2009): highly

recommended. And it’s why internet shopping is not enough. I would never have

run across this book on the internet, never known to Google “poems about

Beethoven,” never known who Dove was. Occasionally you have to walk into a

really good, independent bookstore and finger every book on the shelves.Â

I also ran across The Thoreau You Don’t Know (also 2009) by Robert

Sullivan. It looks and sounds like a facile compendium of Thoreavian esoterica,

but it’s actually a brilliant revisionist biography, with the

contradictory virtues of being breezily written yet withal extremely erudite.

Its ostensive purpose is to rescue Thoreau’s reputation from those who think he

was an antisocial “Mr. Nature,” by emphasizing the year he spent in New York

City trying to get a start as a writer, the time he spent in court as expert

witness for property disputes (being a surveyor), and his wise handling of the

family pencil business. Having not had a superficial view of Thoreau myself

(the book convinced me), I didn’t need the revisionism, but I was impressed

with how much mass culture Sullivan delved into in order to anchor Thoreau in

his immediate society, researching 1840s sheet music and ladies’ magazines, and

the changes in agriculture brought about by the depression of 1837. The

bibliography is kaleidoscopically diverse. Oxymoronically a thought-provoking page-turner, the book is a worthy opposite bookend to

Robert D. Richardson’s more introverted Henry Thoreau: A Life of the Mind.Â

Wrong Turn on the Yellow Brick Road

If you imagine that I’m relentlessly driving myself to complete my Robert Ashley book before school starts, you would be correct. I’m not quite going to make it, but I’m very close. This is in addition to having written a piano piece, a viola piece, and two string quartets this summer (and reading three volumes of Taruskin’s Oxford music history). I’m never again going to work this hard during the summer without a compelling financial incentive. This week I transferred all of my interviews with Bob to compact discs, and found that they fill up 18 CDs. Someday when someone writes a proper biography of Bob (as opposed to the intro-to-the-life-and-works I’m doing), all this biographical material could come in handy. I can’t use half of what I’ve got.

There are some good stories in the book. My favorite is that when Bob stumbled across the text that would become Perfect Lives, he was trying to write a screenplay for an updated version of The Wizard of Oz. Also, the kid across the street that Bob grew up playing with became Marilyn Monroe’s gynecologist.

Udderly Amazing Evening

Oops – I was supposed to help publicize that microtonal wunderkind Jacob Barton is giving a concert tonight on the microtonal instrument he’s invented, the udderbot. It’s at 8 PM at the Urbana-Champaign Independent Media Center. In Illinois, in other words. He’s playing his own version of my piece Fractured Paradise, along with works by Susan Parenti, Aaron K. Johnson, Joseph Pehrson, Edwin Harkins, Bohuslav Martinu, and, well, there are a lot of names as you can see for yourself. The udderbot is made of a glass bottle, a rubber glove, and water, yet possesses a range larger than that of the flute. I’ve been very impressed with Jacob’s initiative in performing so much microtonal work out there in the Midwest, and impressed with his own music as well.Â

Leave No Term Unstoned

I found this curious, that in these days in which the erstwhile existence of an Uptown-Downtown split in new music has been forcibly shoved down the memory hole, an organization called The Field is sponsoring a workshop to bring Uptown and Downtown artists together. Their definitions:

For the purposes of this program:

• An Uptown Artist is an artist who lives and/or focuses their creative activities or aesthetic above 110th Street.

• A Downtown Artist is an artist who lives and/or focuses their creative activities or aesthetic south of 14th Street.

One’s Offspring Affirming Chaos

You can’t hear my son Bernard say anything in this Revolver magazine interview with his black metal band Liturgy, but you can watch him look cool. He claims the things he said got edited out, but he’s kind of a quiet guy. Didn’t get it from me. I’m shy around people I don’t know, but I tend to blossom when you stick a microphone in my face.

Have I Written String Quartets?

I finished another string quartet today – or at least, a piece for string quartet. See, I was asked to write a string quartet, and my original idea was to write one in three movements. I’m not much of a three-movement kind of guy, though, and the idea I had for the first movement got too long and too formally all-encompassing to be a movement. So it grew into an imposing, probably too-long, 25-minute movement, called The Light Summer Land. To title it just String Quartet seemed misleading. But I still had these ideas for the other movements, so I went ahead and wrote the third one anyway. It’s a four-part canon at the major sixth, 13 minutes long, called Hudson Spiral – a companion piece to my nine-part triple canon Chicago Spiral, which I wrote in Chicago, and now I live in the Hudson Valley. I’ll probably finish the second movement as well, and that’ll be another independent piece. I don’t think they can all fit in the same, wrist-slittingly long piece, being based on unrelated ideas.Â

Tracking a Former Student

Yesterday James Sinclair – emperor of all things Ivesian, who heroically catalogued all 8000 pages of Charles Ives’s manuscripts – took me on the Ives walking tour of Yale. While a student there Ives lived in Connecticut Hall, then as now the oldest building left on campus, which, because of its age, tended to house the less affluent students. His dorm room was on the second floor, the last two windows on the right:

Rewards of Musicology

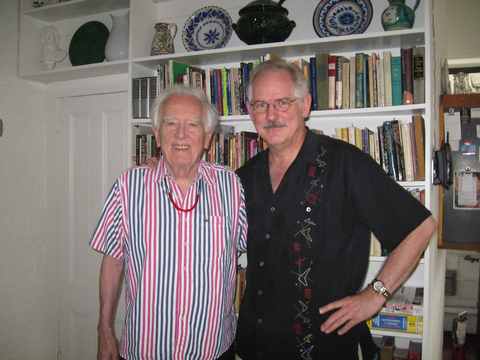

In Ann Arbor I took photos of the houses Robert Ashley grew up in. (Old phone books in libraries, I’ve discovered, are a cheap way to chart history.) I showed him this house on Brookwood where he lived as a teenager -Â

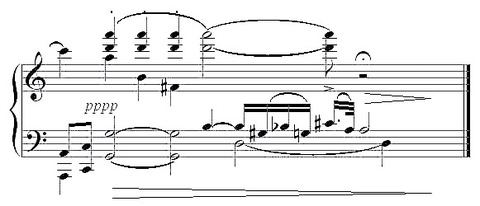

Second-Guessing Chuck

NEW HAVEN – I played the last two movements of the Concord Sonata in high school, and the final four articulated notes of “Thoreau” – G# Bb G C# – have always bothered me. I remember arguing with my piano teacher about them. They don’t seem to have much motivic resonance with the rest of the movement, and the final ambiguous tritone always struck me as un-Ivesian. So now I’m at Yale library looking through the Ives archive, and I’m finding that Ives’s original manuscript presented a different picture. The original ending, which was followed in the 1920 edition but was dropped for the Arrow Press Edition, followed that C# with a dotted-rhythmed A: