I find it difficult to credit this, since my blog is so peripheral to my activities in general – merely an adjunct to my professional writing, which is already an adjunct to my teaching, which is itself something I do to support my composing – but this blog entry seems to indicate that Postclassic is number 5 among the top classical music blogs. Geez, Louise, what an easy profession. Frankly, I think listing me one notch above Sandow is bogus. He gets a lot more traffic than I do. (Besides, this is a POST-classical blog. How about a listing of the top postclassical blogs, huh? Who’d be number one then, Alex Ross?)

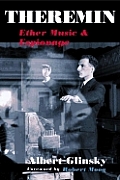

While I’ve got my blog formatting page stoked up, would you like a recommendation on a Christmas gift for music lovers? Albert Glinsky’s Theremin: Ether Music & Espionage is the most exciting music biography I’ve ever read. There are a lot of good biographies, but very few subjects this astounding: Leon Theremin was not only a music-technology genius, but a KGB agent involved in some strange stuff, who disappeared and was presumed dead for decades as he was actually implicated in international espionage. Glinsky’s page-turner reads like a detective story, and he fills in gaps in his subject’s mysterious life with the sometimes hilarious pop history of the theremin. Anyone remotely interested in new music should have this fascinating, effortless read.

While I’ve got my blog formatting page stoked up, would you like a recommendation on a Christmas gift for music lovers? Albert Glinsky’s Theremin: Ether Music & Espionage is the most exciting music biography I’ve ever read. There are a lot of good biographies, but very few subjects this astounding: Leon Theremin was not only a music-technology genius, but a KGB agent involved in some strange stuff, who disappeared and was presumed dead for decades as he was actually implicated in international espionage. Glinsky’s page-turner reads like a detective story, and he fills in gaps in his subject’s mysterious life with the sometimes hilarious pop history of the theremin. Anyone remotely interested in new music should have this fascinating, effortless read.