Everyone has web sites that he or she returns to compulsively in idle moments, and my new one, which I learned about from a comment on New Music Box, is the International Music Score Library Project at http://imslp.org/wiki/Main_Page, a rapidly growing collection of PDF scores from the entire history of music. (Unable to remember the cumbersome title, I’ve started thinking of it as “I’m-asleep.org.”) You would imagine that the site would fill up quickly with Beethoven symphonies and Brahms chamber music, but actually the variety and the obscurity of the musical offerings are quite stunning.

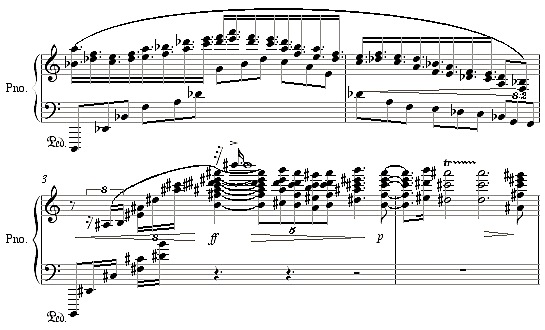

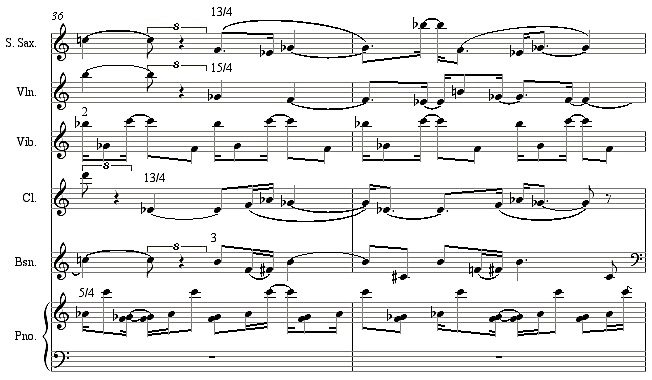

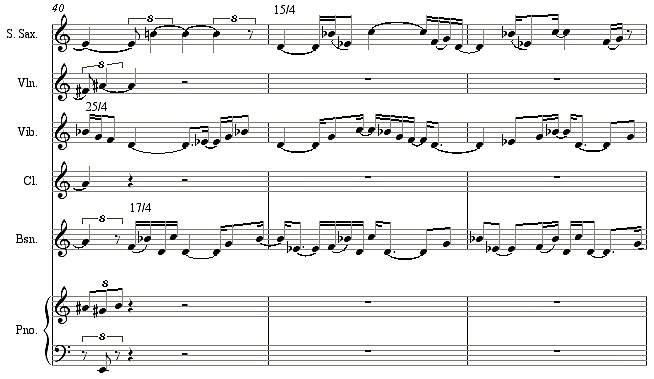

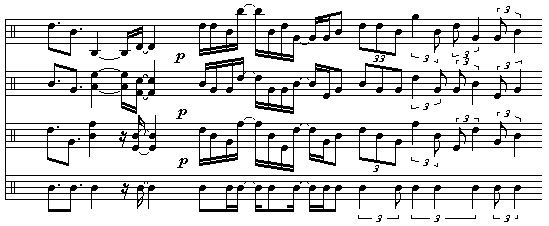

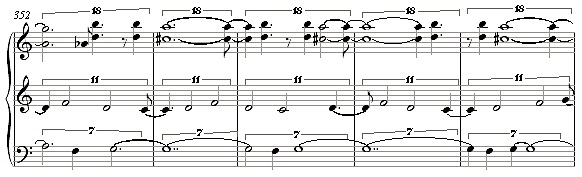

My most exciting find so far has been the 36 Fugues, Op. 36, of Antonin Reicha (1770-1836), Beethoven’s teenage-years friend from Bonn. Reicha professed unbelievably advanced (for the time) theories about music and about the fugue in particular. He advocated for odd meters; the 20th fugue is in 5/8 (with the subject answered at the tritone rather than the fifth), the 24th is in virtual 7/4 (4/4 alternating with 3/4), and another one in 3+3+2/8. They were written in 1803. Reicha ended up teaching at Paris Conservatoire, where Liszt and Berlioz were among his pupils, and sent his old friend Beethoven a copy of the fugues; old Ludwig tossed them aside with the comment, “The fugue is no longer a fugue.” One of the fugues has simply a single repeated note as a subject; another is built on the theme from Mozart’s Haffner Symphony, and their modulatory propensities are sometimes as striking as their rhythmic oddities. I’ve been fascinated by them since Tiny Wirtz’s recording came out (the premiere recording) on CPO in 1992, and am astonished to suddenly find a score. (MDG has also released a charming and rather Czech-sounding Reicha orchestral overture in 5/8 meter. He also speculated about quarter-tones, long before Liszt and Busoni. The earliest explicit use of quintuple meter I can find, by the way, seems to be the mad scene in Handel’s Orlando. One of the Obrecht masses has a passage with a repeating five-beat isorhythm, but of course there was no way to notate quintuple meter in that era.)

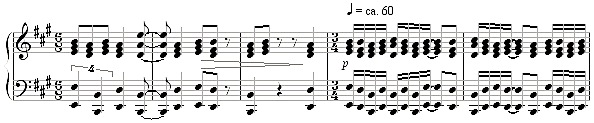

My first, 1997 Village Voice article about internet web sites was entitled “Weirdos Like Me,” enthusing about the other crazy people who vomited forth their obscure passions on the internet, and many of those weirdos, it seems, are uploading to imslp.com. Here you will find a two-piano score to Max Reger’s Piano Concerto (one of his most elephantine and least gratifying works, but one I’ve been trying to familiarize myself with lately); Arthur Foote’s Piano Quintet, perhaps the finest chamber work of the American 19th century; Anatoly Liadov’s lovely little high-register piano piece The Music Box; Busoni’s wonderful Piano Concerto in a two-piano version, which a friend had finally bought me in Germany a few years ago; and Kaikhosru Sorabji’s astonishingly forward-looking First Piano Sonata of 1919. I’ve now got the Concord Sonata in PDF form, as well as the Second and Sixth Nielsen Symphonies, and several early Dussek Sonatas for which I can find no recording. In recent weeks the number of scores expanded from 6000 to 7000 in only 20 days, and one of my favorite features is the “Recent Additions” on the main page, which I check daily to see what’s been added. A couple of days ago I wanted to show a student an example from Holst’s The Planets, without having to drive to my office for the score, and there it was.

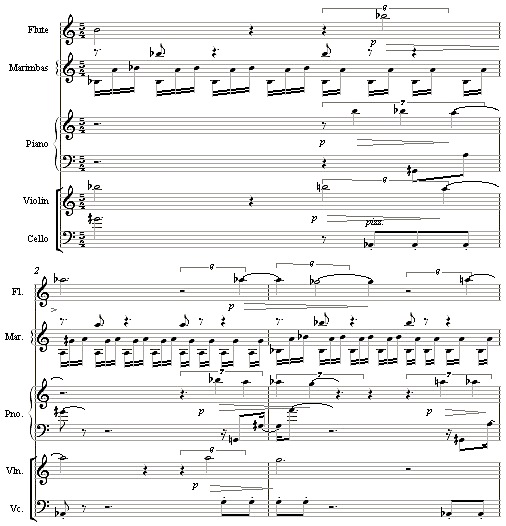

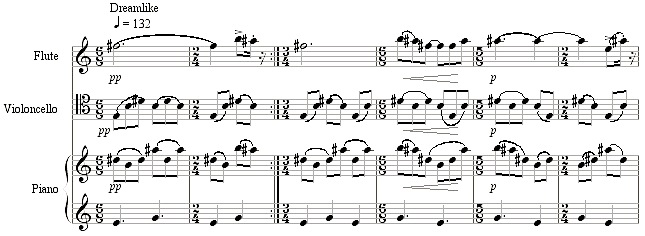

Submissions are limited by copyright restrictions, as you can imagine, and so there are few recent works, and hardly any postclassical ones; though you will find In C and an intriguing flute and piano piece by electronic genius Chris Brown. Living composers are encouraged to add any works they are willing to release into public domain, or under a Creative Commons license. I toyed with the idea, but my available scores are easy enough to find on my web site for those who are looking for them. It’s tempting to consider the people who might run across my pieces without imagining that they might find them at kylegann.com, but I am reluctant to relinquish so much control. So for now I’m not joining in the uploading frenzy, but I’m having a blast benefitting from it. The crazies who are releasing their eccentric music collections to the world have my immense gratitude.