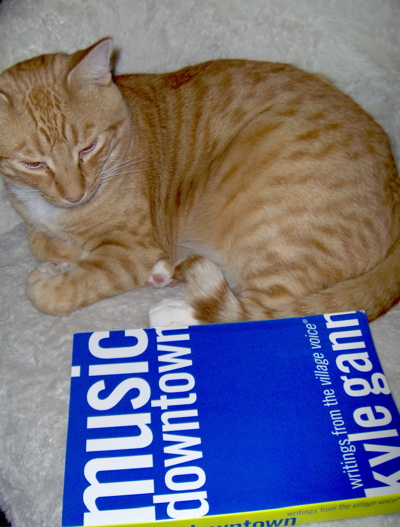

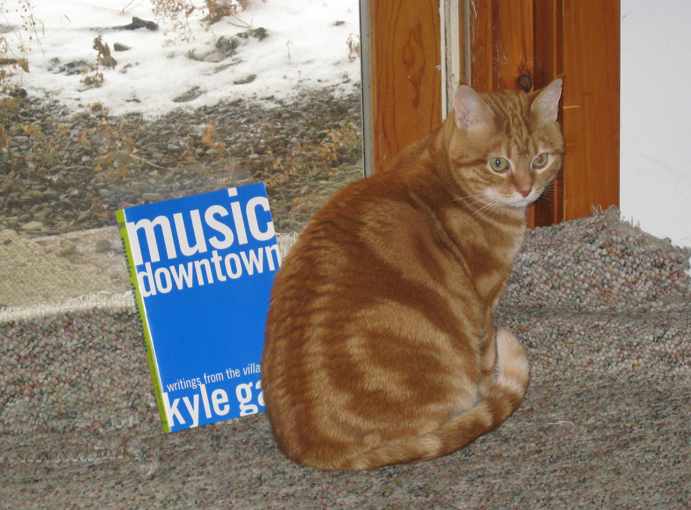

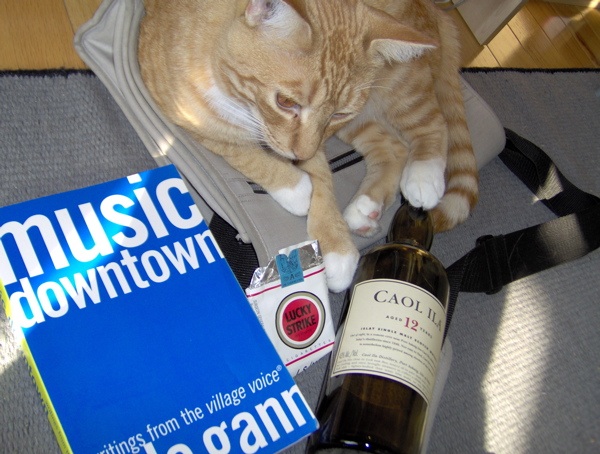

Corey Dargel has an update on the state of his cat, Mr. Bojangles, whom he feels was led down the primrose path to decadence by my book:

But I have a different interpretation. The way I see it, reading Music Downtown educates a feline, or anyone else, in the rewards of the well-spent Downtown life. Replace those Lucky Strikes with a box of Padron cigars, and Mr. Bojangles will have “imbibed,” so to speak, the book in exactly the spirit in which I wrote it. (Or is that spirits?)