DJ Tamara, Trimpin, Arthur Sabatini (hotsy-totsy postmodern theorist and narrator of Bill Duckworth’s Cathedral ensemble):

Elodie Lauten and John Luther Adams:

Composers Max Giteck-Duykers, Nico Muhly, Judd Greenstein, and Alexandra Gardner onstage talking to the audience:

Me and John Shaw, blogger of Utopian Turtletop:

Now will you believe we’re not the same person? (I had just glimpsed the ghost of Ferruccio Busoni over the photographer’s shoulder.)

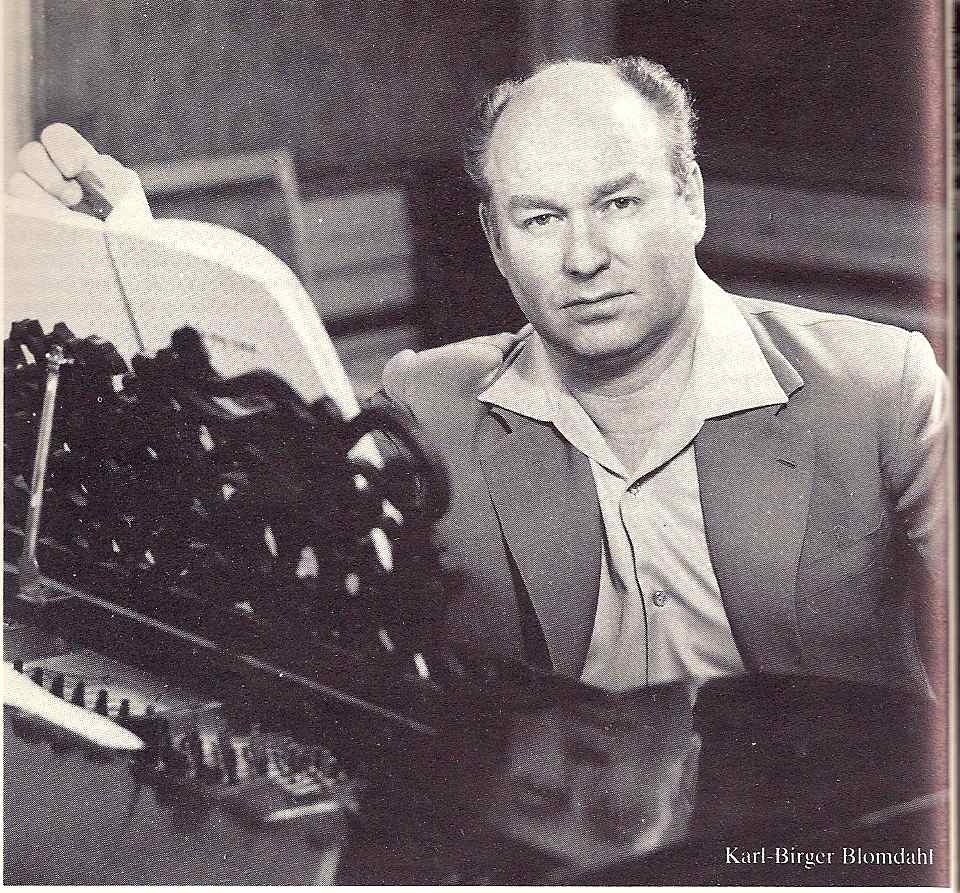

Based on an epic poem by Harry Martinson (1904-78), who I gather was one of Sweden’s most important poets, and set in the year 2038, Aniara is the story of a space ship taking passengers from Earth (named Doris in the fanciful text) to Mars. In swerving to miss an asteroid the space ship is throw off course, and heads off into the infinite. Meanwhile, radio reports reveal that the Earth has been destroyed by nuclear explosions. Act I shows the passengers entertained by a kind of pop singer named Daisi Doody, who sings in a catchy kind of Swedish scat, and a comedian named Sandon, as they try to absorb the tragedy that’s befallen them. Act II takes place 20 years later, the passengers having fallen into decadence and cult worship as main characters die off and the journey reaches its inevitable oblivion.

Based on an epic poem by Harry Martinson (1904-78), who I gather was one of Sweden’s most important poets, and set in the year 2038, Aniara is the story of a space ship taking passengers from Earth (named Doris in the fanciful text) to Mars. In swerving to miss an asteroid the space ship is throw off course, and heads off into the infinite. Meanwhile, radio reports reveal that the Earth has been destroyed by nuclear explosions. Act I shows the passengers entertained by a kind of pop singer named Daisi Doody, who sings in a catchy kind of Swedish scat, and a comedian named Sandon, as they try to absorb the tragedy that’s befallen them. Act II takes place 20 years later, the passengers having fallen into decadence and cult worship as main characters die off and the journey reaches its inevitable oblivion.

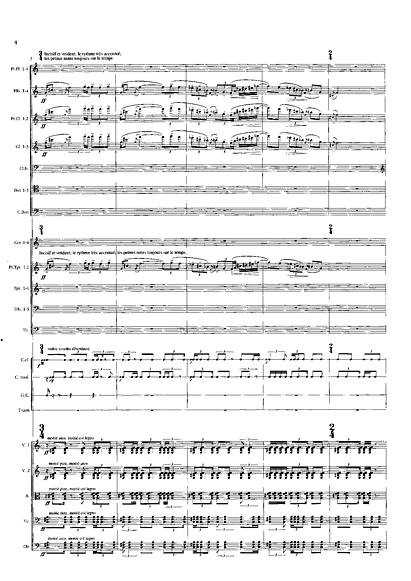

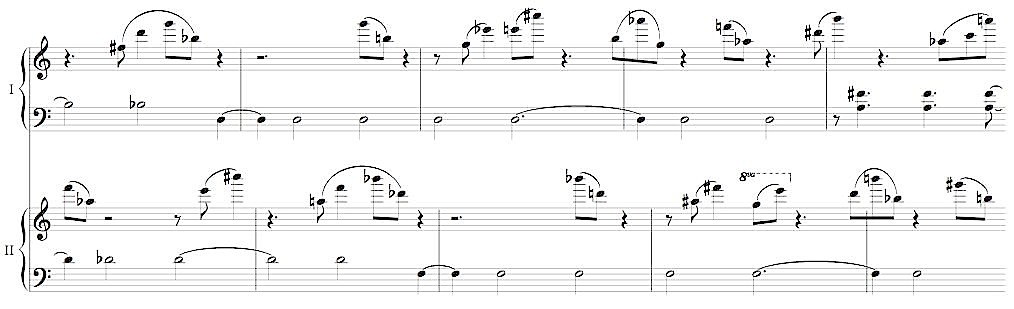

What I can do, though, is tell you about the most astonishing composer I learned about there: Matthijs Vermeulen. The Dutch call Vermeulen (1888-1967) “the Charles Ives of Holland,” and also their Varèse. He is the archetypal undiscovered composer. His Second Symphony – considered by many his most groundbreaking work (second page pictured below) – received its first performance in 1953, and Vermeulen himself first heard it in 1956. He had written it in 1920. The tone clusters, polyrhythms, percussion, and atonal counterpoint it opens with are easily as daring as anything Varèse would write in the next decade. To throw yet another comparison in, the Dutch refer to it as “the Dutch Sacre du Printemps.” Curiously modest about promoting their national composers, they won’t tell you anything about Vermeulen unless pressed, but if you mention how remarkable he was, they look proud as punch.

What I can do, though, is tell you about the most astonishing composer I learned about there: Matthijs Vermeulen. The Dutch call Vermeulen (1888-1967) “the Charles Ives of Holland,” and also their Varèse. He is the archetypal undiscovered composer. His Second Symphony – considered by many his most groundbreaking work (second page pictured below) – received its first performance in 1953, and Vermeulen himself first heard it in 1956. He had written it in 1920. The tone clusters, polyrhythms, percussion, and atonal counterpoint it opens with are easily as daring as anything Varèse would write in the next decade. To throw yet another comparison in, the Dutch refer to it as “the Dutch Sacre du Printemps.” Curiously modest about promoting their national composers, they won’t tell you anything about Vermeulen unless pressed, but if you mention how remarkable he was, they look proud as punch.