The other day I heard a music publisher inveigh against composers who post their scores for free as PDFs on their web pages. I am one of that tribe. His argument, which was new to me and interested me, was that those composers pose unfair competition to the composers whose scores are published, and thus cost money. I have trouble crediting this argument. As much as I’d love to think that my music has an inside track because people can get the scores for free, it’s difficult for me to believe that any performer or ensemble ever makes a repertoire choice based on the cost of the score. The only such cases I’ve ever heard of are orchestras that have decided against performing certain pieces because the orchestral parts cost too much to rent, and those cases didn’t even involve living composers. I suppose it’s possible that if, say, John Adams were giving his scores away for free and David Del Tredici wasn’t, perhaps there are a few ensembles who would choose Adams over Del Tredici for that reason, but I doubt even that. It seems to me that people choose repertoire based on what music fits their ensemble, or their performance technique, or their stylistic programming, and score prices are hardly so exorbitant as to become a determinant.

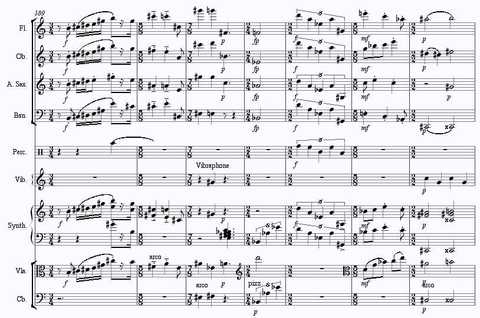

1. The notation needs considerable work to be readable; these are pieces that are either microtonal (often in indecipherable MIDI notation), or partly improvisatory, or electronically produced without a full score, or incidental music for a dramatic production that would hardly make sense out of context, or otherwise insufficiently notated.

2. Scores that were commissioned by performers who requested temporary exclusivity over performance, and I consider such exclusivity rather expensive, though certainly negotiable.

3. Scores on which I imagine that I could eventually make a considerable amount of money. The only score that falls into this category so far is Transcendental Sonnets, of which I post the orchestral score but not the vocal score or the two-piano performance version. Choral pieces have the potential of selling a tremendous number of vocal scores because so many singers are involved, and so I have thought it unwise to send vocal scores out into the world for free – although I have done that with My father moved through dooms of love, which has no score other than the full score. Since I will gladly send a PDF of the vocal score to any chorus interested in a performance, even this small scruple on my part seems superfluous, though I might change that policy if the piece became wildly popular.