I just finished reading, and immensely enjoyed, A Talent for Trouble, the biography of film director William Wyler, by my fellow Arts Journal blogger Jan Herman. Two things at the end of the book struck me.

One was Wyler’s feeling about color photography, which he was late to switch to. “A red chair doesn’t look unusual in reality,” he once said, “but on the screen, you can’t take your eyes from it. That’s because the frame itself is not natural. It’s delimited by the blackness surrounding it. We don’t actually see that way with our natural field of vision. I was late in using color partly because I felt color could be phony, exaggerated.” More evidence of what I’m always saying, that art is about appearances, not reality. A lot of young composers, I think, as well as older ones, make bad music because they’re focussed on what the music really is, not on the way it appears to the audience.

The other point of interest was an encounter with Alfred Hitchcock. Wyler made all kinds of films: westerns (The Westerner, The Big Country), comedies (Roman Holiday), war films (Mrs. Miniver, Memphis Belle), social commentary (The Best Years of Our Lives, Dodsworth), suspense films (The Letter, The Collector), a musical (Funny Girl). One of Jan’s themes throughout the book is that this versatility worked against Wyler’s reputation, since in the ’60s an auteur theory arose that (over-) valued each director’s idiosyncratic viewpoint, and demanded that he turn out films exploring the same themes over and over. Hitchcock, “master of suspense,” benefitted from this, but Wyler called him “a prisoner of the medium.” Once Hitchcock admitted to Wyler that he was jealous: “You can do any kind of film you want. I can’t. They won’t let me.” (Watch Hitchcock’s late comedy The Trouble with Harry, and you might conclude that it was a good thing they didn’t let him.)

Auteur theory is a big subject in film criticism, but its musical counterpart, though quite patent, is hardly discussed. Many of the most well-regarded recent composers are those who evolved an immediately recognizable trademark in their music: Feldman, Reich, Scelsi, John Adams, Meredith Monk, Charlemagne Palestine, Branca, and most of all Phil Glass, who has taken recognizability to an extreme that has ruined him for more sophisticated circles. Interestingly enough, this seems more true of the famous Downtown composers than of the Pulitzer crowd – it’s difficult to imagine reliably recognizing a work by Corigliano, Zwilich, Harbison, or those guys in ten seconds of a drop-the-needle test. (Babbitt’s an interesting case – uniformity not necessarily leading to recognizability.) I suspect that this partly accounts for Europe’s preference of Downtown Americans over Uptown ones, since Europe is where auteur theory originated and flourished. They seem to like our composers who carve out their own distinctive groove.

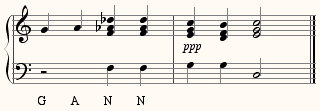

This is a personal issue for me, because, creatively, I find myself much in sympathy with Wyler. I too write static minimalist pieces (Long Night, The Day Revisited), wild collages (Petty Larceny, Scenario), microtonal pieces (Triskadekaphonia, How Miraculous Things Happen), jazz harmony pieces (Bud Ran Back Out, Private Dances), atonal pieces (The Waiting, I’itoi Variations), grand pieces for chorus and orchestra (Transcendental Sonnets). (I’m not the only Downtowner in this boat; Jim Tenney and Larry Polansky have similarly kaleidoscopic outputs.) Inside my head, my musical reflexes are so fixed and repetitive that I feel like I keep writing the same work over and over again, but I have trouble believing that my music comes off that way to the listener, and I sense that people have trouble figuring out what my central style is. I have a repertoire of melodic tendencies that I’ve nurtured closely for 30 years, and a few rhythms that have become absolutely fetishistic, but they recur disguised by widely ranging contexts. In that respect I’m really a little like Nancarrow, who used the same melodic and rhythmic tics in every piece, but whose music – if you brush aside the fact that it’s almost all for the same instrument – runs the entire gamut from meticulous discipline to improvisatory abandon, and from modernist abstraction to boogie-woogie.

Since I so admire so many of the auteur-type composers, I had always intended to gravitate toward a small set of ideas and explore them over and over, as my friends John Luther Adams and Peter Garland have. If nothing else, it strikes me, in the current climate, as a good career move. But my muse doesn’t take directions very well, and it just works out that after writing a motionless Zen essay I’ll next get inspired to write a chaotic parody, and then a postminimalist dance. Jan discounts the claims of the auteuristes and praises Wyler’s versatile ability to adapt to each new genre. It’s in my own best self-interest to ride in that bandwagon myself.