Just before leaving for Europe I chanced to pick up a vocal score of Karl-Birger Blomdahl’s science fiction opera Aniara, and I’ve only recently had time to spend with it. I won’t divulge the used bookstore where I found it, because they acquire a certain amount of modern scores from estate sales (lots of Henze and Berio lately), and I seem to be their prime buyer at the moment – though I must add that their prices seem outrageously high at times. (I’ve also bought scores to Brant’s Angels and Devils, Riegger’s Dichotomy, John Adams’s Chamber Symphony, and some Henze piano music, among other things.) However, Aniara was a piece I reviewed for Fanfare back in the ’80s (the 1985 Caprice recording), and when I saw the score, I knew I wouldn’t resist temptation for long, so I just grabbed it. The piece made something of a splash when it premiered in 1959, got reviewed in Time magazine, and was filmed for TV in 1960. Yet today neither recording nor score seems available. Aniara struck me as one of the most engaging, and at the same time among the least pandering, of modern operas. That it and Blomdahl (1916-68, pictured below – I scanned it because I can’t even find an image of him on the internet) have fallen so far off the radar screen seems unfair.

Based on an epic poem by Harry Martinson (1904-78), who I gather was one of Sweden’s most important poets, and set in the year 2038, Aniara is the story of a space ship taking passengers from Earth (named Doris in the fanciful text) to Mars. In swerving to miss an asteroid the space ship is throw off course, and heads off into the infinite. Meanwhile, radio reports reveal that the Earth has been destroyed by nuclear explosions. Act I shows the passengers entertained by a kind of pop singer named Daisi Doody, who sings in a catchy kind of Swedish scat, and a comedian named Sandon, as they try to absorb the tragedy that’s befallen them. Act II takes place 20 years later, the passengers having fallen into decadence and cult worship as main characters die off and the journey reaches its inevitable oblivion.

Based on an epic poem by Harry Martinson (1904-78), who I gather was one of Sweden’s most important poets, and set in the year 2038, Aniara is the story of a space ship taking passengers from Earth (named Doris in the fanciful text) to Mars. In swerving to miss an asteroid the space ship is throw off course, and heads off into the infinite. Meanwhile, radio reports reveal that the Earth has been destroyed by nuclear explosions. Act I shows the passengers entertained by a kind of pop singer named Daisi Doody, who sings in a catchy kind of Swedish scat, and a comedian named Sandon, as they try to absorb the tragedy that’s befallen them. Act II takes place 20 years later, the passengers having fallen into decadence and cult worship as main characters die off and the journey reaches its inevitable oblivion.

OK, it’s not exactly a feel-good opera, and it’s largely 12-tone to boot. But the row is a simple expanding series – C B Db Bb D A Eb Ab E G F F# – and the simplicity of that structure unites the work in clearly audible chromatic tendencies:

Consequently, the harmony always seems to be expanding or contracting, and the choral passages are among the most singable and followable in the 12-tone repertoire. Boulez would probably have pronounced this kind of technique simplistic, but it possesses the right density for music theater, not too dissimilar in this respect from Wozzeck – and, truth be told, there’s something about science fiction, this “woo woo we’re in outer space” feeling, that makes the discomforting 12-tone idiom ring more plausibly. In addition, the chromatic aura is cut by and blended with two other idioms. One is a kind of Swedish outer-space bebop that attends the “Yurg” cult around Daisi Doody – by which I mean that it doesn’t sound like Blomdahl’s trying to write bebop, only that he’s created a hybrid music indebted to it. The other idiom is the electronic music used for various sequences, such as when the computer-like being Mima is transmitting images of the Earth destroying itself. This admirably smooth fusion of atonality, bebop, and electronics must have been unutterably hip in 1959, and given the recent long-lived wave of conservatism we’ve lived through (musically and otherwise), I have to think that if Aniara were reintroduced today as a brand-new work, within the opera world it would still seem just about as daring in its mashup of idioms as it did then: postclassical before the fact.

In fact, one of the first things I did in Europe was to visit the American expatriate composer Wayne Siegel in Aarhus, Denmark, who teaches electronic music at the Royal Conservatory. (My profile of him just appeared in Chamber Music magazine.) And Siegel played for me excerpts of his own science fiction opera, Livstegn, or “Signs of Life” (1993-94), about a scientist plunged into a personal crisis by his unexpected discovery of intelligent life on one of Jupiter’s moons. Here were the same melding of live instrumentals and electronics, only instead of 12-tone, the work’s background style is postminimalist. Livstegn hasn’t been performed since its premiere run in 1994. It deserves revival, and an American premiere, as does its remarkably parallel distant cousin Aniara.

Why do such works get marginalized from the narratives of contemporary music? Because their composers are not from the approved countries from which excellent music is supposed to spring? I’m glad to own the vocal score to Aniara, and if I ever teach a course dealing with 12-tone technique – which has crossed my mind at times, believe it or not – I think I’d use it as a particularly clear and flexible example. And since I hate describing anything to you you can’t listen to, here’s an mp3 of Scenes 1 and 2.

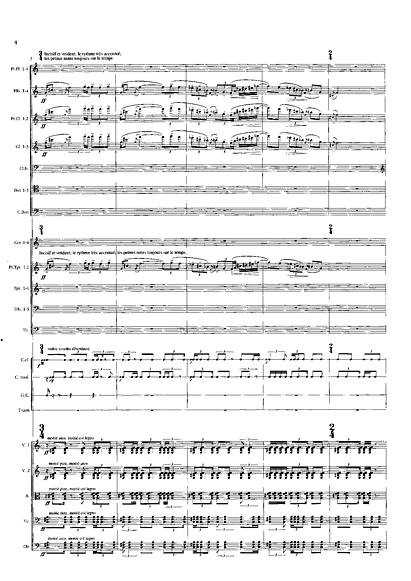

What I can do, though, is tell you about the most astonishing composer I learned about there: Matthijs Vermeulen. The Dutch call Vermeulen (1888-1967) “the Charles Ives of Holland,” and also their Varèse. He is the archetypal undiscovered composer. His Second Symphony – considered by many his most groundbreaking work (second page pictured below) – received its first performance in 1953, and Vermeulen himself first heard it in 1956. He had written it in 1920. The tone clusters, polyrhythms, percussion, and atonal counterpoint it opens with are easily as daring as anything Varèse would write in the next decade. To throw yet another comparison in, the Dutch refer to it as “the Dutch Sacre du Printemps.” Curiously modest about promoting their national composers, they won’t tell you anything about Vermeulen unless pressed, but if you mention how remarkable he was, they look proud as punch.

What I can do, though, is tell you about the most astonishing composer I learned about there: Matthijs Vermeulen. The Dutch call Vermeulen (1888-1967) “the Charles Ives of Holland,” and also their Varèse. He is the archetypal undiscovered composer. His Second Symphony – considered by many his most groundbreaking work (second page pictured below) – received its first performance in 1953, and Vermeulen himself first heard it in 1956. He had written it in 1920. The tone clusters, polyrhythms, percussion, and atonal counterpoint it opens with are easily as daring as anything Varèse would write in the next decade. To throw yet another comparison in, the Dutch refer to it as “the Dutch Sacre du Printemps.” Curiously modest about promoting their national composers, they won’t tell you anything about Vermeulen unless pressed, but if you mention how remarkable he was, they look proud as punch.

A copy of my new CD on the New Albion label, Private Dances, has just been handed to me. The official release date is January 22. My stuff never seems to get out quite in time for Christmas (this happened with Music Downtown two years ago too), but then, I’m not much for participating in American commercialism anyway. I guess.

A copy of my new CD on the New Albion label, Private Dances, has just been handed to me. The official release date is January 22. My stuff never seems to get out quite in time for Christmas (this happened with Music Downtown two years ago too), but then, I’m not much for participating in American commercialism anyway. I guess.