Colin Marshall of Marketplace of Ideas very kindly did a phone interview with me about my book on 4’33”. You can hear the podcast here.

Ending Up at Huntsville at Last

This week, April 15-17, I am the featured composer at the annual new-music festival at Sam Houston State University in Huntsville, Texas. There appear to be six concerts, with my music on four of them, mixed with works by student composers there; click on the link to see the official site. I give a talk Friday morning at 11. I love looking at the list of composers from previous festivals: Peter Mennin in ’62, my one-time teacher Kent Kennan in ’63, Persichetti in ’64, Sandor Varess in ’65, Paul Creston in ’71, Ben Johnston in ’72, Elie Siegmeister in ’91, and several I haven’t heard of. But they brought John Luther Adams in ’07 and Peter Garland last year, and given that progression I do look like a logical next choice. Plus the festival’s directed by Brian Herrington and John Lane, the latter of whom runs their percussion ensemble, and I’ve got several percussion pieces, so I fit in. Also, a lot of their composers are Texas-related, and I’m originally from Texas – though I haven’t had a performance in that state since 1976.Â

Spring 2010 Concert and Event Schedule (April 15th-17th,

2010)

Admission: FREE for SHSU Music

Majors and Music Faculty, $5 SHSU Students, $10 General Public

Thursday, April

15th

Sam Houston State

Student Composers Concert

Recital Hall;

4:00pm

Artist Faculty

Spotlight: Daniel Saenz, Cello Recital

Recital Hall;

7:30pm

Friday, April

16th

Kyle Gann, Guest

Lecture

11:00am; Music

Building RM 202 (subject to change)

The Chamber Music

of Kyle Gann and Sam Houston State Composers (Concert 1)

Recital Hall;

4:00pm

The Chamber Music

of Kyle Gann and Sam Houston State Composers (Concert 2)

Recital Hall;

7:30pm

Saturday, April

17th

Intersection and

the Sam Houston Percussion Group: The Music of Kyle Gann (Concert 1)

Directed by Brian

Herrington and John Lane

Recital Hall;

4:30pm

Intersection and

the Sam Houston Percussion Group: The Music of Kyle Gann (Concert 2)

Directed by Brian

Herrington and John Lane

Recital Hall;

7:30pm – Pre-Concert Talk; 8:00pm – Concert

Â

Redeeming Juvenilia

[Back from Serbia after a 24-hour door-to-door trip in which my plane made an unscheduled stop in Canada because a woman passenger had a seizure and needed medical attention. It was a classic “Is there a doctor on the plane?” situation out of a movie I don’t want to see again.]

Every 29 Years, Saturn

BELGRADE – Saturn is sextiling my Sun and ascendant from my tenth house, if you know what that means. What it means is, I’m kind of difficult to escape at the moment. The always impressive Frank Oteri has a wonderful interview up with me today on New Music Box, in honor of my new book and two recent CDs. I always knew Frank was sort of ridiculously brilliant, but I didn’t realize how brilliant until he started digging into my music and making me see it from a different angle than I’d ever seen it before. In addition there’s another interview with me by John Ruscher on BOMB magazine about my Cage book. There’s also a nice review of my Cage book by Robert Birnbaum at The Morning News. I’m all over the internet today. This, too, shall pass.

Vuk Kulenovic: Virginal (he lives in Boston now; some of the best Serbian composers escaped during the ’90s)

Anyone in Serbia?

I don’t know who might be reading this blog in Belgrade, but in case anyone is, I’ll be speaking about my music (and its relation to American precedents) tonight from 6 to 8 at the University for the Arts in Belgrade.Â

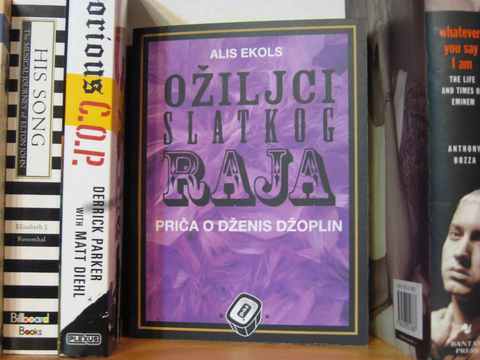

Countries with Sexier Composers than Us

OK, kids, gather around, it’s time for Uncle Kyle to continue your education in Serbian music. I’ve already told you about Ljubica Maric (1909-2003), who was the country’s leading modernist composer of the early 20th century, and the only woman to occupy that position in her country’s culture. Nor will I repeat what I said there about Stevan Stojanovic Mokranjac (1856-1914), the country’s leading musical patriarch and composer of traditional choral music.

Landmark of the Avant-Garde

The great Robert Ashley turns 80 today…

The Damage We Do

BELGRADE – Everyone here’s been very nice to me, but my first lecture happened to fall on the 11th anniversary of the onset of the NATO (mostly American) aerial bombardment of Belgrade, which a few people mentioned. 3.24 is their 9.11 – except that the bombardment lasted 78 days. The city runs sirens at noon every year to commemorate the day. Professional people – authors, musicians, scholars – have told me stories of huddling in their basements, their knees giving way from fear, making their way to the grocery store through the rubble of buildings, having to forego cancer treatments because the hospitals could only handle emergencies. I don’t know much about the politics behind the engagement, and almost don’t want to – though Noam Chomsky considered the NATO attack unconscionable, and I tend to trust him more than anyone. But there’s got to be some way to resolve international disagreements besides dropping bombs in crowded downtown areas, terrorizing civilian populations, and leaving wrecks like these behind, which I photographed down the street from the music school I’m lecturing at:

Well, Damn If It Ain’t Sort of Blue After All

Ba da da da dum (bum, bum – bum, bum):

A Man Grown Silent in the Praise of God

The Dessoff Choir’s March 6 performance of my Transcendental Sonnets, based on poems by the Transcendentalist poet Jones Very and conducted by James Bagwell, is now up on my web site:

A Rolling Stone…

This weekend I’ll be in Ottawa, Canada, for the conference of the Society for American Music. Sunday morning I’m chairing a panel on experimental music theater with respect to Cage and Berio. Then Monday I fly to Serbia, where I’ll be lecturing about my music and American music in general at the University of the Arts at Belgrade for a couple of weeks. I’m sure I’ll be blogging about that, and posting photos. Never been there before, but I have a bunch of Serbian musicologist friends I’ll be glad to see.Â

Floating in Free Pitch Space

Microtonal theorist Timothy Johnson, of whose theoretical skills and even more his work ethic I stand in awe, has sent me the MIDI file he made of the first 30 measures of the final movement of Ben Johnston’s Seventh String Quartet, of which I wrote in my last post. At 2:41, this represents about a sixth of the third movement, which must total 16 minutes. I can’t listen to it enough: exotic consonances floating in a totally free, gridless pitch space. This is truly the music of the distant future. He made the file with piano sounds, since MIDI string sounds are vulgarly inadequate, so you’ll have to imagine this played by a string quartet. I wish I thought I would live long enough to write music like this, but I’m too pragmatic, not visionary enough. The score is published by Smith Publications, if you’re interested in studying it yourself.

The Mount Everest of String Quartets

One of the best things the Microtonal Weekend at Wright State University did for me was initiate me into familiarity with Ben Johnston’s Seventh String Quartet. Written in 1984, the piece has never been played. It has a reputation as being the most difficult string quartet ever written. Timothy Ernest Johnson of Roosevelt U. gave a paper analyzing the third movement (his doctoral dissertation is on the entire work and also Toby Twining’s Chrysalid Requiem), and for the first time I learned exactly wherein that difficulty consists.

If you know much about Ben’s Third Quartet, you know it works its way measure by measure through a 53-note microtonal scale. The finale of the Seventh is built on a similar plan, but the structural tone row consists of 176 pitches – all different, 176 pitches within one octave, heard in the viola on each successive downbeat. Many other notes are heard in the other instruments whose harmonies link each note to the next, and Tim tells me that altogether there are more than 1200 discrete pitches in the movement – more than one per cent, five times as many as most people can perceive. That does sound a little tricky to play. Tim demonstrated how the players are supposed to proceed from the opening C to the subsequent D7bv-, a pitch ratio of 896/891. The violist is tasked to move upward from this C and come back down on a pitch 9.7 cents higher – just under one tenth of a half-step – than she started on. At the downbeat of the next measure, the violist lands on Dbb–, pitch ratio 2048/2025 – another ten cents higher. And so on for another 175 measures until the viola ends up traversing the octave and ends at C again. A good half of Tim’s paper was spent talking us through the performance challenges of the first two measures. Between the first and second downbeats (pictured below), the quartet is supposed to tune the F to the C and the Bb- to the F, the Ab- and Eb- in the cello to the Bb- in the first violin and the 7th harmonic G7b- above that, and find the 11th subharmonic below G7b-, and, voilà , viola, you’re on D7bv-. It’s just 4/3 x 4/3 x 2/3 x 2/3 x 7/4 x 8/11, and bob’s your uncle, there’s your 896/891. It can’t be too much more difficult than four people traversing a 177-meter tightrope together without holding hands, or manually flying four biplanes in parallel in and out of the mountains through a dense fog. I mean, it’s not like they’re calculating all this while playing an accelerating tempo canon, for god’s sake.

The tempo is slow and the rhythms relatively simple, though there are serialized aspects to the rhythm and meter, correlated to pitch differences in the row. Ben recalled that his original proportional scheme would have made the piece last 48 years. Tim Johnson was applauded by others in the audience who had tried to untie this Gordion’s knot and failed; he’s been working on it for five years, and developed a set of computer programs to help him process the cascades of pitches and ratios. Best of all, he played a MIDI version of the movement’s opening 30 measures. It was, indeed, breath-taking: consonances slid into slightly new consonances in recurring patterns, but with no sense of a background fixed pitch grid whatever. [UPDATE: Tim kindly sent me the MIDI file to post, so listen for yourself. It’s done with piano sounds, so imagine a string quartet playing it.] I think I can truly claim that never, in the history of the world’s music, has such deeply-layered complexity sounded so translucent.

I have bowed low before many an unfathomable musical achievement, but before this one

I absolutely prostrate myself. Imagine Ben writing in pencil, in 1984, a string quartet that would later require multiple computer programs to unravel again! How can a mere MIDI-piano version of 30 measures of a yet-unperformed work change your ideas of what music can achieve? Boulez and Stockhausen, you are hereby blown out of the water, your musical understanding has been revealed as merely rudimentary by this Burj Khalifa of sonic conceptualization. The Kepler Quartet, from whom violinist Eric Segnitz was present for the conference, is expected to record the piece for their series of Ben’s complete quartets on New World. Good. Luck.

Thankfully, due to another analysis paper by Daniel Huey of U. Mass., we also got to hear Ben’s Tenth Quartet (1995), which I’d also never heard before. This is a considerably simpler piece, and in fact the final movement is a theme and variations on the tune “Danny Boy,” which isn’t revealed until the very end. The harmonies are tight, fluid, elegantly voice-led, and creamy. The Kepler’s next CD (SQs 1, 5, and 10) comes out in October, and I guarantee you’ll enjoy the 10th. Its simplicity-within-complexity and complexity-within-simplicity will gratify biases all across the spectrum, and with its resonantly pure yet exotic chords it just sounds great.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

In other news drawn from the colloquium (which was astonishingly dense with relevant news, considering it flew by in a mere 29 hours), the other honoree was the late piano tuner Owen Jorgensen, who wrote the massive book on the history of keyboard tuning manuals in English, Tuning (I won’t take the time to look up its voluminous subtitle). Momilani Ramstrum of Mesa College talked about Jorgensen’s life and said that he rather embarrassed Michigan State as their staff piano tuner by becoming more of a celebrity than most of the faculty, so they made him a full professor and let him teach piano tuning. On the other hand, registered piano technician Fred Sturm of UNM gave a polite but exhaustive tirade against Jorgensen’s influence, charging that since he limited himself to British sources, and Britain was a few decades behind the Continent on tuning issues, he’s created a misleading picture of tuning history that others (myself included) are now quoting uncritically. This sounds perfectly plausible, and doesn’t interfere with the pleasure I get from Jorgensen’s passionate speculations about the relation of composing to tuning. However, it turns out there’s a new tome in English now by Patrizio Barbieri simply called Enharmonic which contains a more accurate and voluminous documentation of the history of tuning all across Europe and across the centuries. You can obtain it, as I soon will, at Barbieri’s web site, and I will expect you all to have read it before I blog on the subject again. Frank Cox passed around a copy, and it looks massively impressive.

Microtonal guitarist John Schneider, slapping an endless series of interchangeable fretboards on his axe, started us out with a 100-minute introduction to the history of tuning that hit every salient point, made every principle clear, demonstrated every nuance beautifully on the guitar, and was thoroughly delightful and entertaining. If you ever need a lecturer on this topic, he’s your man. I couldn’t have done it. In five hours or 15 weeks I can make a lot of good points about tuning, but he’s distilled it into a compact traveling road show. And John Fonville led a group of students though a continuum of perfectly tuned tone clusters in Partchian otonalities and utonalities whose beauty we could all appreciate. He’s looking to take that to various schools as well. If I can ever get these guys up to Bard, I will jump at the opportunity.

Ben Johnston offered some lovely reminiscences on his education and career, which microtonal composer Aaron Hunt quotes on his blog, so I refer you there. Aaron gave his own colorful presentation on the microtonal instruments he’s selling through his HÏ€ company, to whose web site http://www.h-pi.com/index.html I additionally direct you. Thanks to Franklin Cox and Wright State University for a colloquium that delivered more punch per presentation than just about any academic event I’ve

ever attended.

I’ll only add that, in addition to what Aaron quotes, Ben Johnston and I shared a moment I’ll never forget. After my address in his honor, he hugged me and said, “Thank you, thank you, thank you.” I replied, “Ohhhh, thank you.” And he looked me right in the eye with the old twinkle I remember from decades past, and growled cheerfully: “You’re welcome!” False modesty on his part would have been devastating at such a moment. For him to acknowledge some small honor I could pay him was pleasant, but for him to acknowledge what he’d done for me - spinning my life off in a direction I hadn’t anticipated, yet one that expressed perfectly what I needed to do – was ten thousand times more fulfilling. If decades hence any student ever thanks me for my impact on his or her life, I’ll remember how important the words “You’re welcome” can be.

\

\