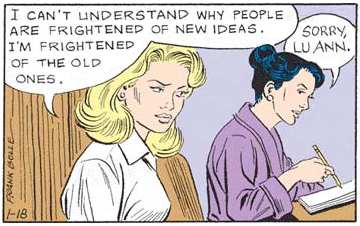

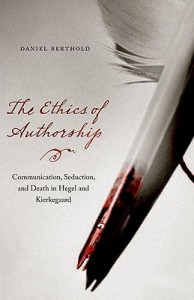

Last night my philosopher colleague Daniel Berthold gave a reading from his new book The Ethics of Authorship: Communication, Seduction, and Death in Hegel and Kierkegaard. I haven’t read the book, but will have to now. He’s a very impassioned speaker, and talked eloquently about the implications of writing in one style or another, and how no style is ever ethically neutral. In passing he referred to eleven tricks he’d discovered that help philosophers get their papers published in journals, and how every trick will make your writing worse. So afterward I asked him about these tricks. Among them: having lots of footnotes; using citations from articles by the editors of the journal; attacking some particular writer or viewpoint; putting the main point early in the article (which he doesn’t like to do, and given the crescendoing style he exhibited, I can see why); and so on. He admitted having learned to use these when he was untenured, and regrets having “sold out” to that extent, however temporarily. Coincidentally, another philosophy professor friend of unconventional leanings had just written me a note about how difficult it is to fight the “empty professionalism that surrounds one in a university.” I think of my colleagues in the more academic departments as being more at home in this environment than I am, and it’s interesting to find that even they find their creativity curtailed, their most sparkling assets as humans and scholars turned into professional liabilities.Â

Last night my philosopher colleague Daniel Berthold gave a reading from his new book The Ethics of Authorship: Communication, Seduction, and Death in Hegel and Kierkegaard. I haven’t read the book, but will have to now. He’s a very impassioned speaker, and talked eloquently about the implications of writing in one style or another, and how no style is ever ethically neutral. In passing he referred to eleven tricks he’d discovered that help philosophers get their papers published in journals, and how every trick will make your writing worse. So afterward I asked him about these tricks. Among them: having lots of footnotes; using citations from articles by the editors of the journal; attacking some particular writer or viewpoint; putting the main point early in the article (which he doesn’t like to do, and given the crescendoing style he exhibited, I can see why); and so on. He admitted having learned to use these when he was untenured, and regrets having “sold out” to that extent, however temporarily. Coincidentally, another philosophy professor friend of unconventional leanings had just written me a note about how difficult it is to fight the “empty professionalism that surrounds one in a university.” I think of my colleagues in the more academic departments as being more at home in this environment than I am, and it’s interesting to find that even they find their creativity curtailed, their most sparkling assets as humans and scholars turned into professional liabilities.Â

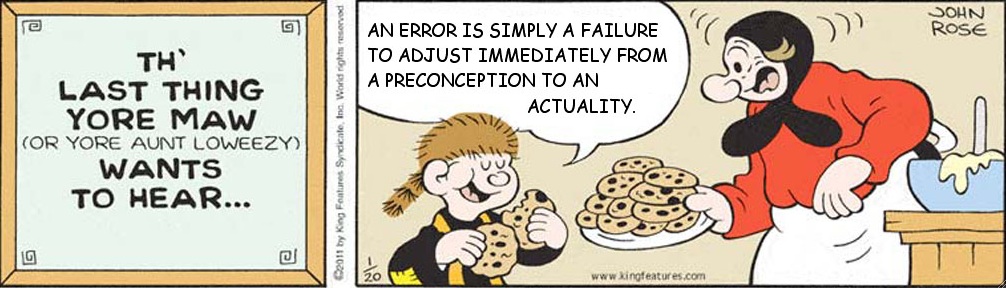

Meanwhile, a talented and recently graduated young composer just told me that his composition professors wouldn’t allow him to write music with a steady beat – because it was “shallow.”