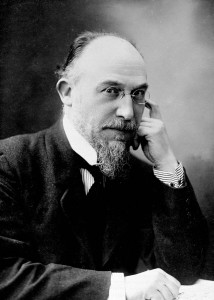

I awoke this morning to the rude shock of learning that my close friend Elodie Lauten has died, a fabulous composer whose music I’ve been championing ever since I was at the Chicago Reader in the early 1980s. Earlier this year I wrote her to congratulate her on winning the Robert Rauschenberg Award, and it took her quite a few days to respond. She said she had been in the hospital, lost a kidney to cancer, and was having trouble walking. We shared a couple more e-mails, and she sounded upbeat about the then-upcoming performance of Waking in New York, her lovely oratorio of Allen Ginsberg poems. Her last Facebook entry, praising the previous day’s performance with no hint of any trouble, was June 2. Apparently she didn’t recover, however, and died yesterday in Manhattan’s Beth Israel Hospital. At 63. (Born 1950, she shared a birthday with Ives, Oct. 20.)

I awoke this morning to the rude shock of learning that my close friend Elodie Lauten has died, a fabulous composer whose music I’ve been championing ever since I was at the Chicago Reader in the early 1980s. Earlier this year I wrote her to congratulate her on winning the Robert Rauschenberg Award, and it took her quite a few days to respond. She said she had been in the hospital, lost a kidney to cancer, and was having trouble walking. We shared a couple more e-mails, and she sounded upbeat about the then-upcoming performance of Waking in New York, her lovely oratorio of Allen Ginsberg poems. Her last Facebook entry, praising the previous day’s performance with no hint of any trouble, was June 2. Apparently she didn’t recover, however, and died yesterday in Manhattan’s Beth Israel Hospital. At 63. (Born 1950, she shared a birthday with Ives, Oct. 20.)

I wrote about her music recently in connection with the award, and won’t repeat that here. I will add that she was more of a martyr to her music than anyone I’ve known. Over the past couple of decades she moved to cheaper and cheaper apartments, and worked temp jobs to make ends meet. She got an occasional gig teaching electronic music or composition lessons thanks to Dinu Ghezzo, who was a guardian angel to her. Despite her near-penury, she was constantly working on getting her big operas, song cycles, and music theater pieces produced. She was as broke as any musician I’ve known, and yet she had more big projects on the front burner than most composers in far more cushy circumstances. I can’t help but think that, on some level, she worked herself to death. It’s an incomprehensible shame, because she had once had a big piece at Lincoln Center, and she always got good reviews – she was my number one example of a composer whose music delighted critics but never seemed to catch on with anyone else. Certainly her tuneful brand of postminimalism has not been in fashion lately, which affects many composers of my generation. She deserved a much bigger career. But I’m hardly the only one who thought so, and she had a crowd of supportive musicians determined to help get her music out. Her keyboard works are charming. Her vocal works deserve a big box set on Nonesuch, if not Deutsche Grammophon. She never wrote a bad piece. She was an oddly quirky, ever-upbeat personality with a touch of Zen mysticism. I kept thinking she would finally get her due someday. She just had to.

UPDATE:This reminiscence of her at Unseen Worlds rings very true.