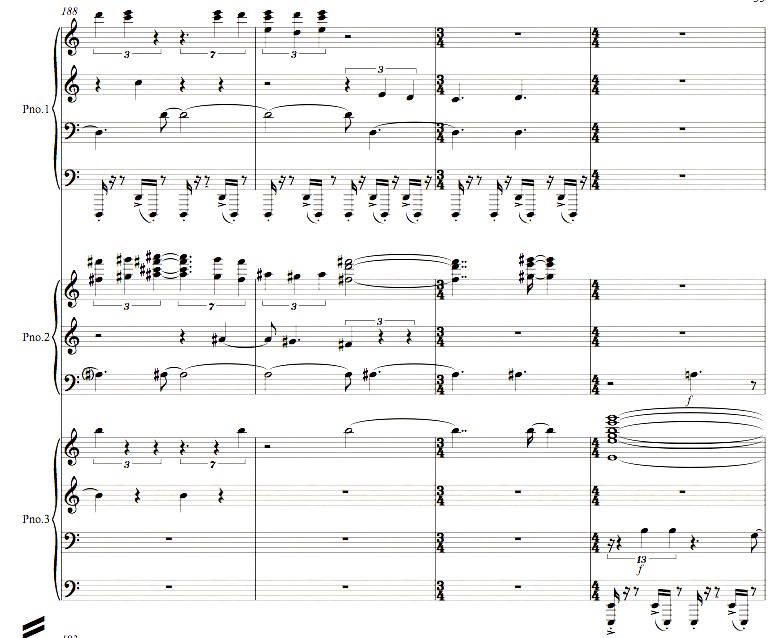

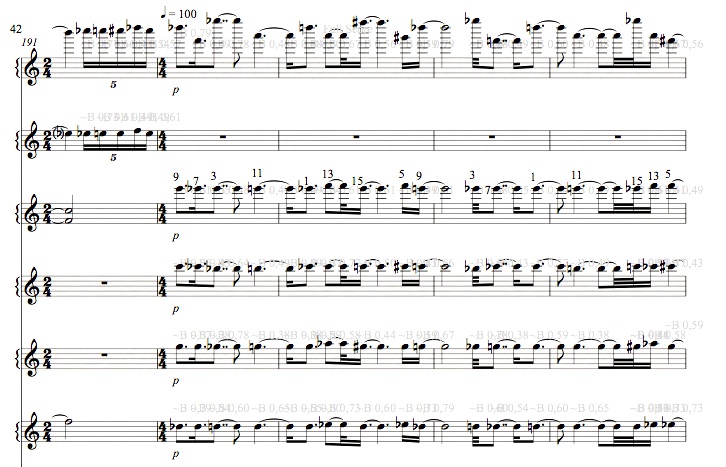

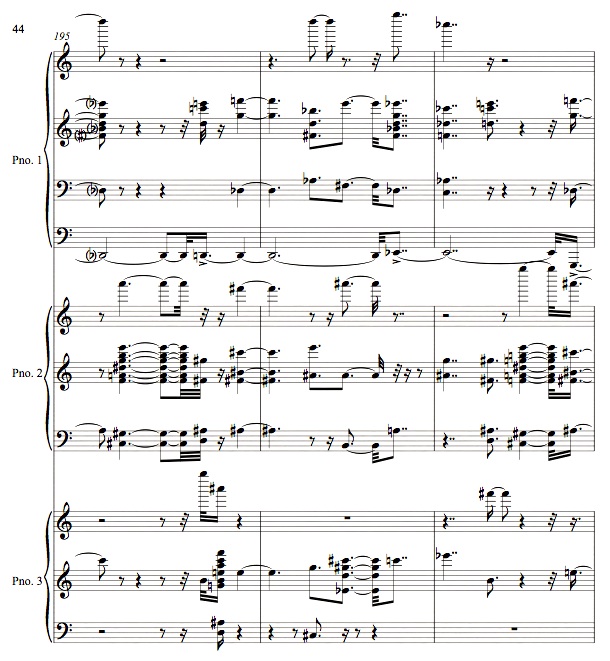

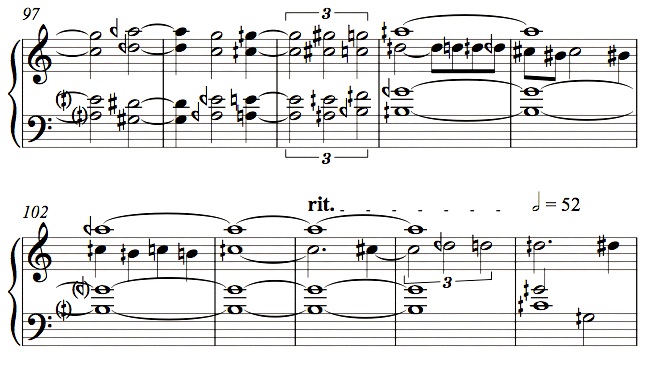

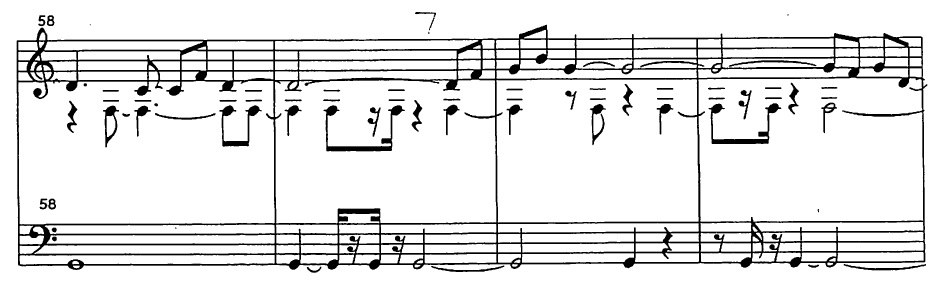

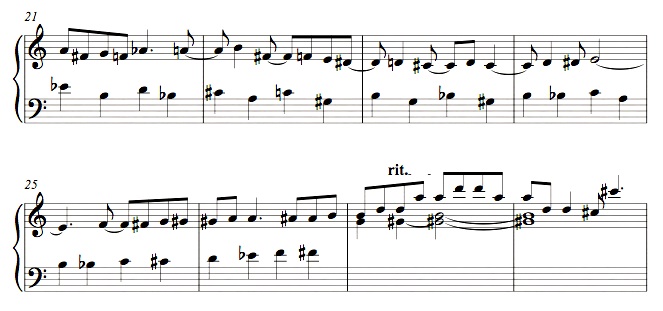

Another three-Disklavier piece in my 33-pitch 8×8 tuning:

Futility Row (2015), 8:53

It’s in the key of E-13-flat minor. That is, since my 1/1 is E-flat, the tonic here is the 65th harmonic (major third of the 13th harmonic), 27 cents sharper than E-flat. I have a penchant for minor keys, and it’s difficult to write a minor-key piece in a scale constructed from harmonic series’. I gained a new empathy for Haydn, who, in his minor-key symphonies, always seems to modulate into the major as quickly as possible. Schoenberg remarked that Chopin was lucky because, if he wanted to do something that sounded new, all he had to do was write something in F# major. Well I’m way ahead of Chopin, because not only am I the first to write something in E-13-flat minor as far as I know, I have lots of other exotic keys left to use. This is a particularly Gannian piece in form and gestural style. But I got the idea while humming a song by Mikel Rouse, and so I dedicate it to him, whose music has so often been a means of bringing me back to earth.