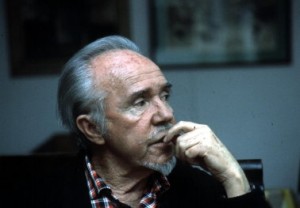

I am not much given to commemorating accidents of the calendar – anniversaries, centenaries, and so on – but given my history with the subject, I would be remiss, I think, if I failed to note that Conlon Nancarrow was born a hundred years ago today. Next weekend I will be in Berkeley for the Nancarrow at 100 conference/festival being presented by Other Minds. I have been interviewed frequently these last few months for radio programs and newspaper articles on Cage and Nancarrow, and I haven’t received many of the URLs at which those interviews ended up; perhaps you’ve heard or read a couple of them. Most recently composer/critic Andrew Ford interviewed me for an Australian radio program on Nancarrow that was supposed to air yesterday or today, whichever it is down there. I don’t really have much to say about Nancarrow that wasn’t in my book on him, but, as I did in London in April, I suppose I’ll play my edited versions of a few of the “unknown” rolls found unlabeled in his studio. He was – in case anyone missed the point – an amazing man.

I am not much given to commemorating accidents of the calendar – anniversaries, centenaries, and so on – but given my history with the subject, I would be remiss, I think, if I failed to note that Conlon Nancarrow was born a hundred years ago today. Next weekend I will be in Berkeley for the Nancarrow at 100 conference/festival being presented by Other Minds. I have been interviewed frequently these last few months for radio programs and newspaper articles on Cage and Nancarrow, and I haven’t received many of the URLs at which those interviews ended up; perhaps you’ve heard or read a couple of them. Most recently composer/critic Andrew Ford interviewed me for an Australian radio program on Nancarrow that was supposed to air yesterday or today, whichever it is down there. I don’t really have much to say about Nancarrow that wasn’t in my book on him, but, as I did in London in April, I suppose I’ll play my edited versions of a few of the “unknown” rolls found unlabeled in his studio. He was – in case anyone missed the point – an amazing man.