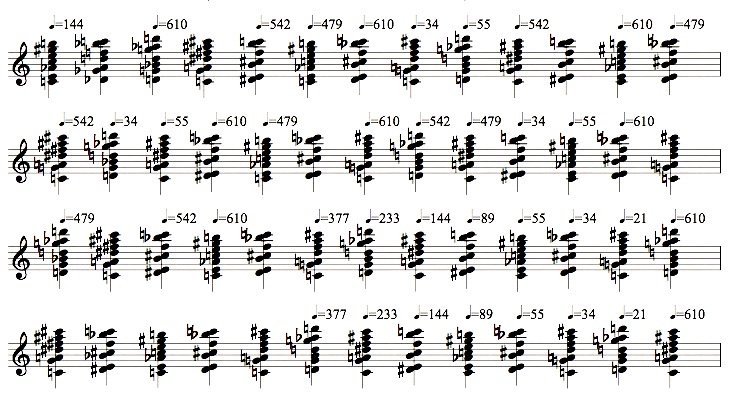

I’m on my way to London this week to give one of the keynote addresses (Charles Amirkhanian is giving the other) at the Nancarrow in the 21st Century conference at the Southbank Centre, organized by Dominic Murcott of the Trinity Laban Conservatoire of Music and Dance. My talk is at 11:15 AM Sunday, April 22. Trimpin will be there, and composer Nic Collins is giving a paper on computer analysis of Conlon’s music, and Conlon’s widow Yoko Segiura Nancarrow, whom I haven’t seen in some 17 years, is making a rare public appearance. And there will be a bunch of concerts, and papers by young composers carrying on Conlon’s polytempo work. I’m planning to present a dozen of Conlon’s “unknown” player-piano rolls, some of them just interesting sketches, others seemingly complete pieces that I think are well worth adding to his canon (pun unavoidable in this instance). I’m playing them on my computer via Pianoteq software, which allows me to harden the virtual piano keys until they sound remarkably like Conlon’s pianos (he put shellac and strips of metal on the hammers to make a more bristling noise).

I’m on my way to London this week to give one of the keynote addresses (Charles Amirkhanian is giving the other) at the Nancarrow in the 21st Century conference at the Southbank Centre, organized by Dominic Murcott of the Trinity Laban Conservatoire of Music and Dance. My talk is at 11:15 AM Sunday, April 22. Trimpin will be there, and composer Nic Collins is giving a paper on computer analysis of Conlon’s music, and Conlon’s widow Yoko Segiura Nancarrow, whom I haven’t seen in some 17 years, is making a rare public appearance. And there will be a bunch of concerts, and papers by young composers carrying on Conlon’s polytempo work. I’m planning to present a dozen of Conlon’s “unknown” player-piano rolls, some of them just interesting sketches, others seemingly complete pieces that I think are well worth adding to his canon (pun unavoidable in this instance). I’m playing them on my computer via Pianoteq software, which allows me to harden the virtual piano keys until they sound remarkably like Conlon’s pianos (he put shellac and strips of metal on the hammers to make a more bristling noise).

Over the succeeding couple of weeks I’ll be lecturing at the Orpheus Instituut in Ghent, Belgium, and at Brunel University back in London, though I don’t think those are public venues. The rest of the time will be pretty much vacation, seeing old friends, and hopefully drinking wine in a slew of outdoor cafés. Conlon would have approved.