You can’t hear my son Bernard say anything in this Revolver magazine interview with his black metal band Liturgy, but you can watch him look cool. He claims the things he said got edited out, but he’s kind of a quiet guy. Didn’t get it from me. I’m shy around people I don’t know, but I tend to blossom when you stick a microphone in my face.

Archives for 2010

Have I Written String Quartets?

I finished another string quartet today – or at least, a piece for string quartet. See, I was asked to write a string quartet, and my original idea was to write one in three movements. I’m not much of a three-movement kind of guy, though, and the idea I had for the first movement got too long and too formally all-encompassing to be a movement. So it grew into an imposing, probably too-long, 25-minute movement, called The Light Summer Land. To title it just String Quartet seemed misleading. But I still had these ideas for the other movements, so I went ahead and wrote the third one anyway. It’s a four-part canon at the major sixth, 13 minutes long, called Hudson Spiral – a companion piece to my nine-part triple canon Chicago Spiral, which I wrote in Chicago, and now I live in the Hudson Valley. I’ll probably finish the second movement as well, and that’ll be another independent piece. I don’t think they can all fit in the same, wrist-slittingly long piece, being based on unrelated ideas.Â

Tracking a Former Student

Yesterday James Sinclair – emperor of all things Ivesian, who heroically catalogued all 8000 pages of Charles Ives’s manuscripts – took me on the Ives walking tour of Yale. While a student there Ives lived in Connecticut Hall, then as now the oldest building left on campus, which, because of its age, tended to house the less affluent students. His dorm room was on the second floor, the last two windows on the right:

Rewards of Musicology

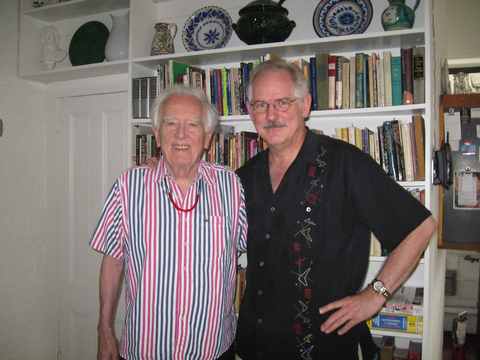

In Ann Arbor I took photos of the houses Robert Ashley grew up in. (Old phone books in libraries, I’ve discovered, are a cheap way to chart history.) I showed him this house on Brookwood where he lived as a teenager -Â

Second-Guessing Chuck

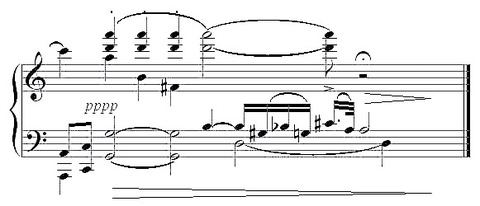

NEW HAVEN – I played the last two movements of the Concord Sonata in high school, and the final four articulated notes of “Thoreau” – G# Bb G C# – have always bothered me. I remember arguing with my piano teacher about them. They don’t seem to have much motivic resonance with the rest of the movement, and the final ambiguous tritone always struck me as un-Ivesian. So now I’m at Yale library looking through the Ives archive, and I’m finding that Ives’s original manuscript presented a different picture. The original ending, which was followed in the 1920 edition but was dropped for the Arrow Press Edition, followed that C# with a dotted-rhythmed A:

Book vs. Music

They noted that there were certain things which were impermanent and other things to which the word impermanence did not apply. – Perfect Lives

I spent June composing and July writing a book. Both are enjoyable and self-fulfilling activities; I am fortunate. The first feels like I’m taking care of myself and developing psychically, putting myself first; the second feels like I’m adding to my authority and piling up ammunition for future writing and debate. It saddens me that the book feels like so much more solid an achievement. The music might never get played, it might get played badly, there might not be a recording, people might not like it or not get it, it may disappear into the ether. The book, being from an academic press, will go into 500 libraries automatically and sit there on the shelves waiting to be tripped over. It will be used by other researchers and quoted in other books. Every time I open the book, it will read just as eloquently as the first time; the music, I’ll have to worry again about every new performance, whether it will go well and sound good. Physically, the result of my composing will mainly be a PDF out on the internet. If I’m lucky and find some money, a compact disc may result, which feels a little bit like a book, but doesn’t get distributed as well. CDs seem to disappear, whereas when I go to friends’ houses, I notice my books sitting on their shelves. Books impress my employers, which my un-prize-winning music doesn’t, and the books bring me lecture gigs, which my music rarely does. (Economically, oddly enough, they’re about the same: I’ve made more money from music commissions than book advances, but the quarterly drip of book royalties offsets that.) After Music Downtown I thought I might not write any more books and just focus on my music from now on, which sounded great. I could do that. But I got seduced back into books as a much easier path toward the appearance of achievement. I could have written all my music and still not be taken seriously by a wide variety of people, but the books (peer-reviewed, published at someone’s expense, permanent, not misunderstandable) give me a kind of irrefutable clout that I can’t deny enjoying. And now I have three more books I’m thinking of working on down the road.

Music is a History of Our Struggle with the Law

This unparaphraseable self-dialogue from Atalanta illustrates something of what I love so much about Robert Ashley’s music:

I said, “Is the struggle with the law manifested in every

aspect of the making of music, or are there law-abiding aspects and others that

are confrontational only because of indiscretion on the musician’s part –

because of a transgression?”

He said to me, “Music is the enactment of the manifestation

of the struggle with the law on a scale of continuous attempts; that is, where

the attempts are related to each other symbolically through a pattern imposed

on our memory. Music is a history of our struggle with the law.”

I said, “Can music, then, substitute itself for the

enactment of the struggle in other parts of our lives?”

He said to me, “That is its most common use.”

I said, “The musician, then, becomes socially symbolic,

enacting restlessness.”

He said to me, “Yes. In order to be law-abiding, there has

to be a place where one can rest. One can be law-abiding only in safety from

the law.”

I said, “Is the listener different from the musician?”

He said to me, “Yes, that is the paradox of music. In

listening to music we are observing other persons like ourselves, but the

consequences of their actions do not accrue to us actually. Their actions are

understood only in retrospect. The consequences may accrue to us as wisdom. May

even endanger our relationship to the law, may change our minds, but for the

listener the act has already come into existence before the law is recognized.

The listener is in safety from the law.”

UPDATE: Notice how subtly and beautifully it nuances the tone that he uses “He said to me” rather than simply, “He said.” The man’s a frickin’ poet.

Offended by Expertise

In an interview on Slate, Wikipedia cofounder Larry Sanger (who left the organization) confirms the very reasons I quit having anything to do with the web site:

Q. Why did you feel so strongly about involving experts?

A. Because of the complete disregard for expert opinion among a group of amateurs working on a subject, and in particular because of their tendency to openly express contempt for experts. There was this attitude that experts should be disqualified [from participating] by the very fact that they had published on the subject–that because they had published, they were therefore biased. That frustrated me very much, to see that happening over and over again: experts essentially being driven away by people who didn’t have any respect for those who make it their

lives’ work to know things.

Q. Where do you think that contempt for expertise comes from? It’s seems odd to be committed to a project that’s all about sharing knowledge, yet dismiss those who’ve worked

so hard to acquire it.

A. There’s a whole worldview that’s shared by many programmers–although not all of them, of course–and by many young intellectuals that I characterize as “epistemic egalitarianism.” They’re greatly offended by the idea that anyone might be regarded as more reliable on a given topic than everyone else….

And later, just as accurately:

This is a general problem with Wikipedia: What is praised as consensus decision-making or crowd-sourcing often just means that the person with the loudest voice or the most time on his or her hands is the one who’s going to win.

Center of the Universe

We live eight miles from where Chelsea Clinton is getting married this weekend. I walked into my local copy shop, and Jerry asked, “Have you gotten your invitation to the big wedding yet?” I said, “Mine must have gotten stuck in the mail, it hasn’t arrived.” Jerry said, “Yeah, it’s probably sitting next to mine.” No boats are allowed to sail in this stretch of the Hudson for the weekend. The biplanes at the Aerodrome, a popular local attraction, are grounded for the duration. The fairgrounds have been emptied out, because that’s where the helicopters are landing. Two extra sheriffs have been hired, apparently at taxpayer expense. The Clintons are staying with a rich family whose name adorns one of Bard’s most expensive buildings. Residents are pretty much warned to stay away from the town this weekend. The rehearsal dinner is rumored to be taking place at my favorite local restaurant, a joint too pricey for me to dine at except on celebratory occasions. If by any chance Chelsea is a reader of this blog, I highly recommend the macadamia-nut tempura calamari and the garlic soup. They’re fantastic. And mazel tov.

Ashley in the Rear-View Mirror

Robert Ashley’s 1983 opera Atalanta is actually three operas: one about the painter Max Ernst (uncle of Bob’s wife), one about the jazz pianist Bud Powell, and one about Bob’s uncle Willard Reynolds, the family story-teller and, as Bob calls him, shaman. Any given performance is made up of one act about each hero, and the acts are interchangeable, so one performance will contain one set of stories and the next night a different set of stories. As Bob writes in his “Future of Music” lecture,Â

At the opera I am transported to a place and time

where there is no disorder. There is disorder on stage, and it is called

melodrama. We don’t believe it. This is important: that we don’t believe it. We

do believe… what happens in the movies…. Therefore, opera can have no plot. It

is foolish to argue that opera – any opera – can have a plot; that is, that the

“characters” and their apparent “actions” and the apparent “consequences” are

related in any way. Opera can be story-telling only. That the story-telling

happens on stage and that musicians are making music in the pit (to reinforce

the story told) is entirely coincidental. The story might as well be told at

the kitchen table with a crazy aunt and uncle as the soprano and tenor.

1. Homo agens: man acting, or in conflict (Allegro)

2. Homo sapiens: man thinking (Adagio)

3. Homo ludens: man playing (Scherzo), andÂ

4. Homo communis: man in the community (Allegro)

Homo agens: Improvement: Don Leaves Linda -Â Linda in conflict and acting to ensure her own safety

Homo

sapiens: eL/Aficionado,

the Agent looking back and trying to reconcile his experiences

Homo

ludens: Foreign Experiences, Don Jr. having wild rides with an Indian guide in his imagination

Homo

communis: Now Eleanor’s Idea, Now Eleanor finding her destiny within the Lowrider community

Â

It’s kind of an amazing five-and-a-half-hour operatic symphony. (I also have to wonder why I spend so much time on really, really long pieces, when I don’t write very long pieces myself.)

Scholarship After Google

In the penultimate scene of Robert Ashley’s Improvement: Don Leaves Linda, Linda keeps singing about “Twenty-eight million, two hundred and seventy-eight thousand, four hundred and sixty-six people….” That’s 28,278,466. So I Google the number. I pull up a hundred random sites, invoice numbers, auction IDs, and so on. And there on page three I see the name: “Blue” Gene Tyranny. And “Blue” Gene has written an article in which he mentions Ashley’s early ONCE festival piece Public Opinion Descends Upon the Demonstrators, in which sounds from the audience are amplified. There are six different versions of that piece, depending on the size of the audience. The smallest version is for 6 people in the audience, and, as “Blue” Gene notes, the largest is for 28,278,466 audience members or more. And the first words of Act II of Improvement are: “This act is about – uhn – public opinion.” Turns out for Ashley 28,278,466 somehow symbolizes the end of the world, but he doesn’t remember how he arrived at it. (I’ll spare you the speculation: 28,278,466 factors out to only three prime numbers, 2 x 1097 x 12,889. I couldn’t have figured that out without “factoring large numbers” sites on the internet. And it’s not in the Fibonacci series.)

The Serious 1950s String Quartet

A dutiful part of my research on Ashley has involved listening to music by his composition teachers, Ross Lee Finney, Leslie Bassett, and Wallingford Riegger. For the most part, it is well-crafted, relentlessly earnest, dour, unpersonable music, much of it for string quartet or quintet. I was glad to get that part over with. And then I run into Ashley’s own characterization, in an unpublished but wonderful lecture he gave at UCSD in 2000:

…I like dance music. I like America. I like our innocent people. I am one of them. But I have come to like, as well, another kind of music, which is in conflict, I discover, with the idea of music as something to dance to. I have come to like a new kind of “devotional” music, which has moved out of the churches into some unlocated, secular place. I say “devotional,” because I don’t know a better word, but it is music to be listened to, not danced to. In the listening it takes you to some place you have never been. It is mental. It doesn’t require head-nodding. You just sit there and it flows through you and changes you.

I have brought up this point of the difference between dance music (music to be danced to) and “devotional” music (for want of a better word), because Americans keep trying to arrive at some sort of “compromise.” Check out the term, “accessible.” It almost invariably means the music has a “beat.” I don’t think there is any reason music has to have a beat, unless you are going to dance to it. That is a pleasant aspect of some music. I do it myself. But unfamiliar music that doesn’t have a beat is being discriminated against. The composer knows this. And so the composer is always trying to compromise….

There was a brief few decades, early in the century, when the better-off went to Europe (Germany, in particular) to catch up with non-dance music. Charles Ives didn’t go. But everybody else went. They brought back imitation German music. It was good in Germany, but here it was imitation. Then, in this “serious” music there was a brief flirtation with jazz, which mostly came to nothing, because the black people were better at jazz. And black people could not make “serious” music, because they were oppressed. Then (this is a chronology) there came American-Serious-Music. It was taught in the conservatories. Every music school had a Resident String Quartet (the cheapest form of ensemble), a Graduate Student String Quartet, and numberless Undergraduate String Quartets. They played American-Serious-Music. The string quartet was the university computer-music-studio of the 1940s and 1950s… It is a characteristic of the string quartet to emphasize moving the bow back and forth. The more the better.

Insert: Mr. Arditti, of string quartet fame, complained to Alvin Lucier, in the presence of a large number of people, that he didn’t like to play Alvin’s String Quartet, because there was very little bow movement, which lack of bow movement made his arm tired. To which Alvin replied, “Why don’t you play it with the other arm?”

American-Serious-Music became a matter of moving the bow back and forth as much as possible, with accents here and there. You might call it sawing. One of its foremost practitioners called the style, “motor-rhythmic.” It is characterized by a continuous sawing of sixteenth-notes or eighth-notes (depending on the time signature and the tempo). Up-bow, down-bow, up-bow, down-bow, endlessly. You know what i mean. This is where I came in. I went to music school. I hated “motor rhythms.” Gradually I came to hate string quartets, when they got into that sawing, because that relentless sawing was simply a senseless update of the circle-dances that those innocent people had brought with them to America…. Everything about “motor rhythms” was just another version of the polka, the hora, and whatever else the dances were called wherever they came from. A circle of mostly poor people holding hands and jumping up and down. A long way from Morton Feldman. And I didn’t even know Morton Feldman existed.

I print this here because I think it’s wonderful reading, wonderfully put, and an insightful reading of the times. This is not to say I would have said everything he says the way he says it – I have my own thoughts about what “accessibility” means – but, as usual, I can’t argue with him. He’s a brilliant writer, which has not yet been acknowledged much – so brilliant that even his prose is nearly impossible to paraphrase, so that I end up quoting larger chunks than I’d like to get away with. American-Serious-Music: I know the genre well, and it’s a good term for it. We still have a lot of it around.

I keep running into evidence that musicians have never heard of Ashley. (For instance, last night Bill Duckworth told me his interview with Ashley got axed from his Talking Music book because the editor had never heard of him.) This flummoxes me. Ashley has been at the center of my musical focus since I was in high school in the early ’70s. When we brought him to New Music America in 1982, he was our number-two celebrity, after only John Cage – and much of his best music hadn’t even been written yet. In those days I didn’t have a musician friend who wasn’t into him. I would have easily said he was as famous as Stockhausen. I can only gather that Stockhausen continues to get taught in music departments, and Ashley doesn’t – partly because his insights, such as those above, don’t sit well in those music departments. My book will make the strongest attack on that problem that I’m capable of. I am finding that to really get into some of Ashley’s works I have to go through the text pretty thoroughly – especially true of Foreign Experiences and Now Eleanor’s Idea. It’s a lot less work than reading analyses of Gruppen and Le Marteau, and repays the effort.

Now That’s Musicology

Here’s an author’s query for you. One of Robert Ashley’s biggest influences in college was a piano teacher named Mary S. Fishburne. She was listed, with an M. Mus., as Assistant Professor of Music in the Univ. of Michigan catalogue from 1949 to 1956, at which point she vanishes from history. I can’t find any details about her. If anyone (among my older readers, presumably) has heard of her and has any idea what happened to her, I’d love to hear about it.