1. Don’t talk to yourself

2. Speak only when you’re spoken to

3. Make sense

“Don’t talk to yourself” is a reminder that talk isn’t a part of understanding, but a habit, an arrangement of sounds. The arrangement requires a partner, and thus, historically, marriage followed conversation. “Don’t talk to yourself” means to stop arranging things when you’re alone, and to not use for yourself what belongs to all of us: sounds. “Speak only when you’re spoken to” represents the dilemma of the second historical eon, in which humankind struggled to reconcile its arrangements of marriage and religion, leading to the third eon, in which we make sense: “we have accomplished ourselves, / (Or invented man, as The Philosopher says).”Â

The background here is that Ashley was, at the time, immersed in a 1976 book that I also read when it was new, Julian Jaynes’s The Origin of Consciousness in the Breakdown of the Bicameral Mind. Jaynes’s theory was that the ancients, for example the ancient Greeks, had no communication between the hemispheres of their brain, and received messages from the right hemisphere that seemed to come from outside, and they interpreted those messages as the voice of gods. So, for instance, Agamemnon hearing the voice of Apollo was actually hearing an auditory hallucination from his own brain. Later man learned to integrate the two hemispheres, so the voices no longer sounded like they were coming from outside. The book was controversial at the time, but the nitwits at Wikipedia seem to suggest that it has withstood scrutiny. (All the cockeyed ideas I ingested about left brain/right brain theory started with that book.) At the other end, Ashley was convinced at the time that he had a mild form of Tourette’s Syndrome, in that he sometimes had to leave parties to let off an involuntary stream of words – and it was in recording those words that Perfect Lives began. So he’s actually tracing a presumed history of consciousness from when speech was involuntary and hallucinatory (the eon before “Don’t talk to yourself”) to its use in creating social connections to its reflexive function in a narrative that gives life meaning – the increasingly conscious employment of language. Ed and Gwyn’s wedding is thereby contextualized at that point in human evolution; on top of which, the vegetarian Theosophist Ed is modeled on a guy Ashley knew in high school who wanted to marry his sister, and who is further described in his opera Dust, and so on. The levels never end.

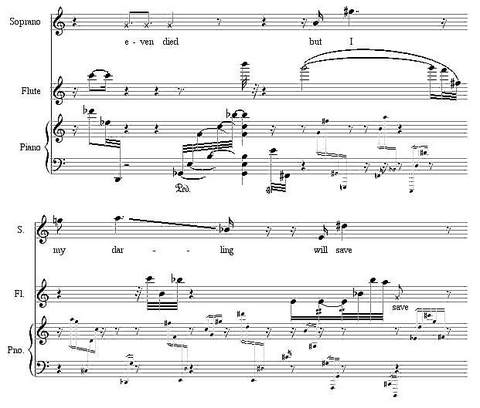

Also Ashley, let us not forget, was kept from getting a music doctorate by my book’s arch villain Ross Lee Finney, so instead he worked at the U. of Michigan Speech Research Lab, funded by Bell Laboratories, doing groundbreaking research on the causes of stuttering. And so Ashley’s given a lot of thought to the purpose and origins of speech for several decades, and the basic idea of his life’s work since 1978 is that language is music. Some people refuse to consider him a composer because they can’t understand this simple, crucial, and scientifically defensible point. His opera Foreign Experiences is full of profanity because profanity is how we slow speech down and attend to its sound rather than its sense; and one of my favorite Ashley lines is one I haven’t retraced to its source yet: “Who could speak if every word had meaning?” And threaded through his operas you find fragments of an epistemology and a philosophy of language, as in “The Church”:

Language has sense built in. It’s easy toÂ

Make sense. To make no sense is possible,

But hard. Language does not have truth built in.

It’s hard to make truth, which is to stop the search.Â

So for Ashley language is an arrangement of sounds (“Sound is the only thing we can arrange”) that is really music, and its meaning is secondary to its interpersonal and aesthetic functions of binding us together and clarifying our arrangements. He says that Jacqueline Humbert (Linda in Improvement: Don Leaves Linda) and his son Sam pick up the intentions of his operas instantly because they’re both from southern Michigan and can catch his inflections: in other words, his operas are about the music of the way southern Michiganders speak.

Now, there are three reactions you can have to all this, and I have all three at once: This is crazy; This is unbelievably profound; and, There’s some scientific or historical truth being presented in this oblique way, and I ought to be able to tease it out. But it’s all poetry, and so resists both paraphrase and explanation. Perfect Lives is, I’ve become convinced, one of the great epic poems in the English language, the Paradise Lost of postmodernism. Ashley is the perfect new composer for nonmusicians, because his operas deal with crucially essential stuff outside the music world. You have to read a lot of books to fully trace Ashley’s steps, and I’m going to have to write my own book and then read those books: otherwise I won’t know what I’m looking for. For instance, I read in Lama Anagarika Govinda’s introduction to The Tibetan Book of the Dead that the “illusoriness of

death comes from the identification of the individual with his temporal,

transitory form, whether physical, emotional, or mental”; and it hits me that, in “The Park,” Raoul de Noget muses,Â

Everything in the transitory category turned out to be

the particulars of our existence,

and these were divided into physical, mental, and others

that were neither physical nor mental.

The more I read Ashley and listen to the details and try to thread it all together, the more awestruck I am. What some commenter here said of Charles Ives is true of Ashley too: he’s so incredible that people can’t believe someone can be that brilliant and insightful and prophetic, so they just assume there’s some hoax going on: the confederacy of dunces phenomenon. I don’t believe I’ve ever encountered a more profound figure in the history of music.