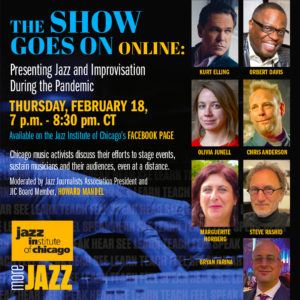

Chicago presenters of jazz and new music, and journalists from Madrid to the Bay Area, vocalist Kurt Elling, trumpeter Orbert Davis and pianist Lafayette Gilchrist discussed how they’ve transcended coronavirus-restrictions on live performances with innovative methods to sustain their communities of musicians and listeners, as well as their own enterprises were in two Zoom panels […]

Future Jazz past: Hal Willner, circa 1992

The death of funny, smart, idiosyncratic, unique music producer Hal Willner at age 64 saddens me. We were East Village neighbors in the go-go ’90s, flush with ideas to try in the future. Here’s my entry about him from Future Jazz (Oxford U Press, 1999). CONCEPT PRODUCER AS VISIONARY “My projects happen mostly by accident,” […]

Luminous PoKempner pix of Sun Ra’s celestial music

Marshall Allen, ageless 94, leads the Sun Ra Arkestra If you liked Black Panther, listen to the music that introduced and embodies Afro-Futurism. Photojournalist Marc PoKempner captured a bit of the celestial magic of the Sun Ra Arkestra (est. circa 1954) during its November touchdown in New Orleans’s Music Box Village. This picturesque venue is […]