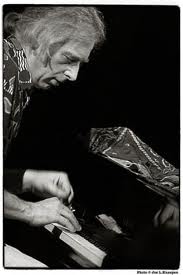

Pianist and NPR “Piano Jazz” host Marian McPartland, age 93, has found a worthy

successor to her post interviewing and duetting with musicians — Jon Weber,  an extraordinarily fluent keyboard artist with encyclopedia depth on many of the earliest styles of American improvised music. Though rather under-recorded, Jon excels at the most intricate (and frequently obscure) compositions of the great stride piano masters (James P. Johnson at their head) as well as writing and arranging his own works, which fall into the modern-mainstream category: tuneful, rhythmically varied, harmonically sophisticated. (Thanks to the Chicago Tribune’s Howard Reich for this news).

an extraordinarily fluent keyboard artist with encyclopedia depth on many of the earliest styles of American improvised music. Though rather under-recorded, Jon excels at the most intricate (and frequently obscure) compositions of the great stride piano masters (James P. Johnson at their head) as well as writing and arranging his own works, which fall into the modern-mainstream category: tuneful, rhythmically varied, harmonically sophisticated. (Thanks to the Chicago Tribune’s Howard Reich for this news).

Jon has served as a host of one of the rooms of the annual Jazz Foundation of America loft benefit parties; I’ve seen/heard him wield the ready wit and engaging stage presence to pull off being almost-live on-air with guest musicians from across genres.

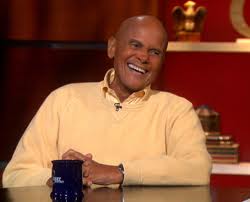

Ms. McPartland, captured in an amatuer video playing “I”m Old Fashioned” at Dizzy’s Club Coca-Colo (in Jazz at Lincoln Center) in 2010, initiated “Piano Jazz” in 1979, and it’s easier t0 name the musicians she hasn’t engaged

in musical dialog than those she has. A sophisticated and gracious woman — when I first met her in 1977 when reviewing her stand at Rick’s Café American in Chicago, she looked me up and down and said, flatteringly, “I was expecting a much older man” — she will be missed but not forgotten; dozens of the “Piano Jazz” shows are archived and she will long be listened to, mixing it up with Bill Evans, Mary Lou Williams, Eubie Blake, Elvis Costello with Allen Toussaint, among many others.

A hard act to follow, but welcome Jon! Come forth swinging.

howardmandel.com

Subscribe by Email |

Subscribe by RSS |

Follow on Twitter