I refrain from abject product endorsement — but The Jazz Icons Series 5 is my no-fail recommendation for those favorite (weird?) aunts or uncles obsessed with “culture” — for parents who space out listening to long, wordless music from their decades’ back youth — for snobs who should meet vernacular jazz in its noblest and most durable […]

Wynton on CBS: the Artist as Cultural Correspondent

Wynton Marsalis has in one swoop become the world’s most prominent jazz journalist. The 50-year-old trumpeter, composer, bandleader, winner of multiple Grammys in multiple categories, author of several books on jazz (all but one co-written), artistic director of Jazz at Lincoln Center, world-traveling ambassador of the American experience, holder of uncountable awards, degrees and honors, […]

Week before Christmas, NYC listening beyond jazz

Richard Bona introduces his Mandekan Cubano project at the Jazz Standard, Dec. 27 through New Year’s Eve — as I detail in my new CityArts-New York column. But from now through December 24 there’s other strong, new music to check out in, especially at Roulette in Brooklyn. Tonight (Dec. 15) and tomorrow (Dec. 16), trumpeter […]

Favorite recordings, 2011 — many more than 10

Lists of top projects of the year are expected from arts journalism – my apologies for being so late this year, but I needed to re-visit many of the the 1200 cds and dvds I received as promotional samples from Thanksgiving 2010 – TG 2011. Â Here are some favorites — top 10 I’ve liked best, […]

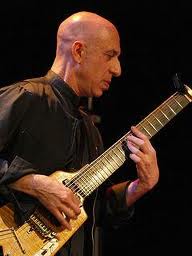

Elliott Sharp @ Roulette – way beyond category

No label exists for the music of composer-guitarist-saxophonist Elliott Sharp, who performed with two of his Carbon concept ensembles at Roulette in Brooklyn last week. In both quartet (Sharp on 8-string guitarbass with electronic processing, curved soprano and tenor saxes, and musicians playing electric bass, prepared harp and drums) and septet (the quartet plus second […]

Orchestrating improvisation

My new CityArts column is about the wave of conducted orchestral improvisation currently sweeping New York City  — with Karl Berger’s Stone Workshop Orchestra and Lawrence Douglas “Butch” Morris’s Lucky Cheng Orchestra wrapping up their lengthy Monday night runs, Elliott Sharp reconvening Carbon at Roulette, Greg Tate’s Burnt Sugar: The Arkestra Chamber at Tammany Hall in a benefit for […]

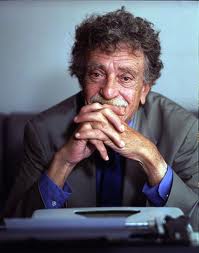

Kurt Vonnegut deserves better

Christopher Buckley’s New York Times Book Review frontpage piece on And So It Goes, Charles J. Shields’ biography of Kurt Vonnegut, is as lazy a bit of evaluation as it’s possible to pick up a paycheck for. I can’t tell from it anything about Shields’ book, and nothing about Vonnegut’s many novels, either. (See “jazz” content at […]

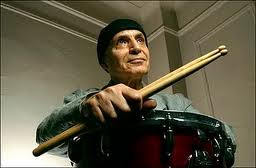

Drummer Paul Motian (RIP) talks, and why he matters

Drummer Paul Motian died November 22 at age 80. He was a unique sound organizer and constant actor on the jazz scene in New York City for nearly 60 years. He spoke to me for Down Beat in 1986 — an interview I offer in slightly different form below. Of course it doesn’t account for […]

Best Thanksgiving 2011 jazz in New York City

The holidays are the best of times and the worst of times for hearing music in New York City. Hosting friends and family, or being a guest on a visit, is great, until it pales. That’s when we look for entertainment options, and going out for jazz seems like the most sociable, something-for-everybody activity. The […]

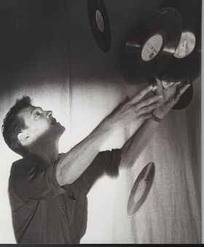

Turntablism — avant noise or early music?

Onstage at the Japan Society before concertizing with Otomo Yoshihide, Christian Marclay told a crowd, “You’re going to see us do some things you’ll think are interesting, but you have to understand how shocking it was to do this in the ’80s, when people treated records as something precious.” And thereby Marclay, famous recently for […]

Shemekia Copeland roils Jazz at Lincoln Center with roadhouse blues

A blues-belter with a beautiful big voice and cred in the rockin’, bawdy, electric tradition, Shemekia Copelandbrought a funky good time to the elegant Allen Room of Jazz at Lincoln Center last Thursday night (and probably Friday, too), backed by a a tight four-man band, carrying a slew of fresh and catchy songs. It’s unusual […]

Iraq vet and New Orleans avant-gardist WATIV on first visit to NYC

Composer and improvising keyboardist William “WATIV” Thompson — Mississippi-born, New Orleans-based and an Iraq war veteran who I profiled for NPR in 2005 (podcast below) when he was posting laptop computer music he created in Bagdad during free time from his counterintelligence duties – made his first visit to New York City last week. I met him […]

West Side Story @ 50 — the soundtrack’s the thing

Celebrating the 50th anniversary of West Side Story — the movie, released October 18 1961, Â not the play which debuted on Broadway in 1957 — for my column in CityArts – New York, I listened to the Bernstein/Sondheim music in many variations. Here’s my report, slightly revised for the web: For West Side Story, the […]