Ushering in 2017 with Patti Smith and band at Chicago’s Park West New Year’s Eve was inspiriting for us of a certain age and artsy disposition. Grey-haired but loose and limber — funny, fierce, profane and poetically incantatory — Smith celebrated her 70th birthday in the city of her origin as if for all boomers and our […]

Jazz warms Chi spots: Hot House @ Alhambra Palace, AACM @ Promontory

There are good arguments for building venues just for jazz. But speaking of arts communities in general: Most are moveable feasts, fluid, transient, at best inviting to newcomers to the table. It’s demonstrable that when jazz players and listeners alight at all-purpose spaces such as Chicago’s Alhambra Palace, where Hot House produced the trio of saxophonist David Murray, bassist […]

Dr. Richard Wang, enabler of AACM experimentalists, RIP

In his first college teaching job at Wilson Junior College during the early 1960s, trumpeter Dick Wang encountered a cadre of exploratory young Chicago musicians who would soon form the AACM (Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians). He encouraged them. He introduced Roscoe Mitchell, Joseph Jarman and Malachi Favors, Anthony Braxton, Henry Threadgill, Ari Brown […]

African roots, Middle Eastern extensions in Hyde Park Jazz Fest

Pianist Randy Weston, a magisterial musician at age 90 inspired by jazz traditions and its African basics, and trumpeter Amir ElSaffar, who has devoted himself to incorporating the Middle East’s modal, microtonal maqam legacy into compositions for jazz improvisation by members of his Two Rivers Ensemble, were highlights of last weekend’s 10th annual Hyde Park Jazz Festival. Both […]

Chi jazz fest 2016, details in photos and words

My DownBeat overview of the 38th annual Chicago Jazz Festival, comprehensive as I could make it, didn’t go into depth on any of the couple dozen performances I heard from Sept 1 through 4 in downtown Millennium Park and the Cultural Center. So here, with imagery by my photojournalist colleagues and friends Marc PoKempner and Michael Jackson (whose photo […]

Thomas Chapin on film, with TromBari in Normal IL

Glenn Wilson, a terrific baritone saxophonist and flutist based in Normal, IL, is also a major mensch. Last Saturday, at the end of Normal’s Sweet Corn and Blues festival, he organized a free concert and screening of Thomas Chapin: Night Bird Song, a comprehensive documentary about his friend, the usually exuberant alto saxophonist, flutist and composer who died of leukemia […]

A Great Migration suite from trumpeter Orbert Davis: Audio interview

Orbert Davis — trumpeter, composer and leader of the Chicago Jazz Philharmonic, has been commissioned by the Jazz Institute of Chicago to write and perform a suite about the Great Migration for the 38th annual free Chicago Jazz Festival. “Soul Migration,” for octet, will be heard Sept 1 at 8 pm in Millennium Park’s Pritzker Pavillion. […]

MCA-Chicago’s Terrace concerts, acing outdoor presentation

Chicago’s Museum of Contemporary Art has aced outdoor music presentations with its Tuesdays on the Terrace series, most recently featuring the string trio Hear In Now performing strong yet sensitive chamber jazz. Drawing a thoroughly diversified crowd to enjoy fresh, creative music in open space on a summer afternoon for free (food and beverages extra) shouldn’t be […]

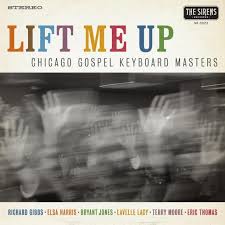

Gospel (not my usual bag) keyboards revelations

I’ll never be an avid fan, much less an aficionado, of gospel music — but Lift Me Up, Chicago Gospel Keyboard Masters, new from The Sirens, a local independent label, is clearly full of joy and inspiration. It also is notable for documenting a seldom spot-lit but obviously thriving American roots music scene. Art arising from or meant to beget religious transcendence […]

Chicago’s free summer music cornucopia – Deutsch, PoKempner photos

With a 10th annual Latin Jazz festival produced in the neighborhood Humboldt Park by the Jazz Institute of Chicago and dynamite downtown concerts with headliners such as Nigerian juju star King Sunny Adé and Afro-Cuban progressive Eddie Palmieri put on by DCASE, the city’s Department of Cultural Affairs and Special Events, Chicago’s free summer music programs […]

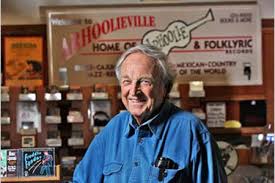

Arhoolie Records (a dozen faves) to Smithsonian

Excellent news on the archival recordings front: Arhoolie Records, the 55-year old treasury of American folk and vernacular musics, has been acquired by Smithsonian Folkways, the non-profit record label of the Smithsonian Institution. So a broad, odd, historic, incomparable cultural catalog, founded and run since 1960 by producer Chris Strachwitz (now 84) enters the public trust. Smithsonian […]

Pulitzer winner Threadgill: “What is harmony?”

My profile of Pulitzer Prize winner Henry Threadgill, commissioned by and published in DownBeat in 2010: Henry Threadgill exuded confidence and impatience when facing four video cameras and a standing-room-only gallery of serious listeners at the Manhattan new music performance space Roulette last October. With his flute, bass flute, alto saxophone and bass clarinet at hand and […]

Threadgill wins Pulitzer for Zooid and cheers for his career

The Pulitzer Prize for Music has been earned by Henry Threadgill, composer, bandleader and reedist, for his expansive and in-depth explorations of polyphonic improvisation with his quintet Zooid, the suite stretching over two cds In for a Penny, In for a Pound. Big time congratulations! And encouragement listening to all and any of Henry’s works, as he is […]