Greg Tate, author-essayist as well as guitarist-leader of the Butch Morris “conductioned” band Burnt Sugar the Arkestra Chamber,n looked for his evidently unpublished liner notes to the planned 25th anniversary reissue on CD of Morris’ Conduction #1, Racism in Modern America, a work in Progress. He couldn’t find them. Tate emailed : “hey man those […]

Wayne Shorter & Orpheus Chamber Orch: Prometheus, promising but self-bound

The Orpheus Chamber Orchestra came to play with saxophonist Wayne Shorter‘s quartet at Carnegie Hall Friday, Feb 1, and — though conductorless — showed the cohesion and verve that will make a jazz-with-symphony program a triumph. If Shorter’s writing and improvisations had matched their readiness, the night could have been truly historic. This orchestra, celebrating […]

Another take on Butch Morris’ Conduction #1, “Current Trends in Racism”

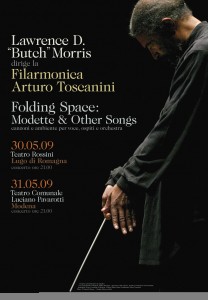

Poet/playwright/critic  Allan Graubard has been a close friend and collaborator with Buch Morris, writing highly descriptive and evocative notes for Testament: A Conduction Collection  as well as their theater work, “Modette,” and the liner notes below, intended for the 25th anniversary re-issue of Conduction #1, Current Trends in Racism in Modern America, A Work in […]

Current Trends in Racism in Modern America, A Work in Progress by Butch Morris

My maybe unpublished 25th anniversary liner notes for Conduction #1, Current Trends in Racism in Modern America, A Work in Progress, by the late Butch Morris with all-star improvisers, recorded 28 years ago today (Feb 1, 2013) and sonically as relevant as ever. [The cast is: Frank Lowe, tenor sax; John Zorn, alto sax and […]

Butch Morris, musical artist and friend, mourned widely

Lawrence Douglas “Butch” Morris, one of the most brilliant and musically generous of artists who emerged from New York’s East Village in the 1980s as an experimental cornetist, composer of melodies and settings, and instigator of the burgeoning act of Conduction (a term he copyrighted), died January 29 of cancer at age 65, and the […]

NEA’s Jazz Masters Live program gets farther, still farther to get

The National Endowment for the Arts is not in its essence a presenting organization. Its annual productions of ceremonies inducting new Jazz Masters, like the one at Dizzy’s Club in Jazz at Lincoln Center on January 14,  are special projects, probably stretching the Endowment’s resources of staff, finances, time and energy. I commented in my last […]

How to recognize NEA Jazz Masters

There is no Golden Globes, Emmies, Oscars or highly hyped Grammys for jazz. So the National Endowment of the Arts’ Jazz Masters award is, as acting NEA chair Joan Shigekawa said at ceremonies crowning its 2013 inductees on Jan. 14, “the greatest honor the nation can bestow” on veteran creators of America’s world-beloved vernacular yet “classical” […]

NYC’s hot Winter Jazzfest, and Macy Gray with David Murray Big Band

The second weekend of January is now the fullest on NYC’s jazz calendar, with continuation of the high energy, two-night showcase Winter Jazzfest in multiple Greenwich Village venues, and aspirational ensembles elsewhere playing (they hope) for booking agents and curators attending the annual Association of Performing Arts Presenters convention. Having responsibilities of my own Friday […]

Images of a Jazz Conference

Jazz Connect, a confederation of jazz activists including principals of JazzTimes magazine,  AllAboutJazz.com and Thirsty Ear Recordings, produced a free multi-meeting conference with no specific theme other than what’s happening in the musical “community” now, on Jan 10 and 11 at the New York Hilton. (Correction: JazzTimes is NOT part of Jazz Connect, but did organize […]

Jayne Cortez — poet, activist, muse of the avant garde — dies, age 76

Jayne Cortez, a no-nonsense poet who often declaimed her incisive lines of vivid imagery tying fierce social criticism to imperatives of personal responsibility with backing by her band the Firespitters, died Dec. 28 at age 76 (according to NYT obit, age 78). Her deep appreciation of American blues and jazz was another of her constant themes; her […]

2012 Top Jazz Beyond Jazz recordings

Checking out new recordings is the motivation of much jazz journalism, though at top-10 time having so much new stuff can be a bedevilment, if not a curse. Here’s a baker’s dozen of my favorites from among the 11-some-hundred sent by record labels, publicists and, increasingly, the artists themselves. They reward multiple listenings, so I keep […]

My suggestion for 2014 NEA Jazz Master: Reggie Workman

Things may be somewhat up-for-grabs at the National Endowment for the Arts, with chair Rocco Landesman  stepping down at year end (NEA Senior Deputy Chairman Joan Shigekawa will serve as the agency’s acting head), but assuming the show will go on I urge Reggie Workman (b. 1937, Philadelphia) receive a 2014 NEA Jazz Masters Award. Workman is […]

“Latin” Jazz Master Eddie Palmieri, both innovator and conservator

Eddie Palmieri is a new NEA Jazz Master — to be inducted Jan. 14 in a ceremony at Dizzy’s Club in Jazz at Lincoln Center, to be webcast live. He is, contradictorily, the spark-plug/conservator of the Americas’ indefatigable Afro-Caribbean music. He turned 76 yesterday (Dec. 15), celebrating with a a “career retrospective” featuring his jazz band and […]