True story, just happened: The cashier at my Brooklyn Shop Rite supermarket asks, “Who’s that on your shirt?” I glance down at my tee, not recalling what I threw on this morning. “Louis Armstrong.” I see it’s one from the Jazz Institute of Chicago, a print of Gary Borreman’s painting of Pops as he looked […]

Archives for 2012

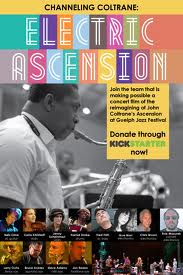

Funding jazz projects: Kickstarter and other pleas

Do-it-yourself practicalities pertain to serious jazz projects — artists whatever their art form do what they must to fund their projects. Hence Kickstarter, the platform that seems to have become the functional alternative to asking wealthy patrons to underwrite expeditions, experiments and print folios. That model worked for Columbus, Edison and Audubon, so why not for Franz […]

Harlem cultural center goes dark, Craig Harris moves on

The end of seven months of Monday music by trombonist Craig Harris’ funky and exciting improvising ensemble at Harlem’s Dwyer Cultural Center is one sad part of an all too common story, told in my latest CityArts column. Even when space for community arts activity is required by the city for real estate development, there’s no […]

Proudly: 2012 JJA Jazz Awards NYC and Auckland videos, photos

The 16th annual Jazz Journalists Association Jazz Awards gala party in NYC is well reported in this video by Michal Shapiro, Huffpo vlogger (her specialty: World Music — isn’t jazz “world music”?): Here’s how they celebrated the Jazz Awards in Auckland — and photos from NYC, Atlanta, San Francisco, among other scenes. howardmandel.com Subscribe by Email or RSS […]

News — good and otherwise — about good radio

WNYC/WQXR program host David Garland makes a good point, in reference to the announcement by WGBH (Boston) that it’s cutting back its nightly “Eric in the Evening” jazz show, Steve Schwartz’s Friday night jazz show and  Bob Parlocha’s overnight jazz show. Writes Garland:  “I wish good radio was considered a good ‘story’ while it’s ongoing, not only […]

News-talk doesn’t replace jazz programming

Of the many postings about Boston radio station WGBH’s misguided downgrading of its signature jazz coverage — managing director Phil Redo has announced the removal of long- beloved prime time show host Eric Jackson to weekends only, the end of producer Steve Schwartz’s Friday night show, and the cut back Bob Parlocha’s overnight program from […]

Why we give Jazz Awards

Winners of the 16th annual Jazz Journalists Association Jazz Awards are being announced at a gala party this afternoon in New York City (at the Blue Note, 4 to 6 pm, sold out!), and celebrated in 13 other cities, Auckland to Tucson, all hailing their own local jazz heroes. Why do we (I’m pres of the JJA) do […]

Jazz and/or free New York City summer music festivals

I love the conjunction of “free,” “jazz,” “festivals,” “summer” and “New York City” Â — though not all free fests are jazz, and not all jazz fests are free (in either of two senses of the word). For instance, the 17th Vision Festival, which I write up in my CityArts-New York column, has some free shows, […]

Happy Moog Day, electronic music fans

Google celebrates the late inventor Robert Moog whose electronic music synthesizer still holds universes of unexplored and unexploited potential on his 78th birthday by making its Doodle a working, recordable monophonic (one-tone-at-a-time, though three oscillators so it can be a complex tone) mini-Moog. A video demonstration explains how to use it, and good luck with that! […]

Marcus Roberts weirds classic jazz, frees banjo’s Fleck

Pianist Marcus Roberts has broad reach and pushme-pullyou ideas, reharmonizing Jelly Roll Morton and improvising freely with banjoist Bela Fleck, as I detail in my latest column in CityArts-New York. At Jazz at Lincoln Center Robert, the blind visionary, led a sextet that hewed to Morton’s structures while incorporating a handful of solo styles from […]

Bassist Duck Dunn – deep, syncopated, bouncy – RIP

Donald “Duck” Dunn, bassist for Booker T. and the MGs, most all the grits ‘n’ greens soul voices who emerged from Memphis’ Stax Records in the 1960s, and dozens of major blues-rock-pop stars during his subsequent career as an LA-based studio musician, died in his sleep at age 70 in the early morning of May […]

The Jazz Gallery seeks new downtown Manhattan home

My latest column in CityArts-New York highlights the search for a new location of the Jazz Gallery, a splendid venue that has been responsible for launching some of the most exciting musicians and freshest projects to emerge in jazz and improvised music over the past 17 years. Commissions, residencies, workshops, rehearsal space and performances not […]

International Jazz Day concert review (few elsewhere)

Read my short-hand review, please, in CityArts-New York of the sunset concert of International Jazz Day in the General Assembly of the UN in New York City. The music of Louis Armstrong, Duke Ellington, Miles Davis, Thelonious Monk, John Coltrane, Billie Holiday, Howlin’ Wolf , Leonard Bernstein and many more was manifest by all-stars of all ages […]